This year was an up-and-down time for film, as audiences cautiously returned to theaters. But even if box office returns were erratic and often disappointing, quality-wise, there was more greatness than could be contained in a top 10 list. Since I hate ranking, here are my personal awards for movie excellence in a weird year.

Worst Picture: Old

“There’s this beach, see, and it makes you old.”

“That sounds great, M. Night Shyamalan! You’re a genius!”

Dishonorable Mention: Malignant

WTF was that about?

Best Memphis Film: “The Devil Will Run”

Director Noah Glenn’s collaboration with Unapologetic mastermind IMAKEMADBEATS produced this funny and moving memory of childhood magic. Glenn topped one of the strongest collections of Hometowner short films in Indie Memphis history.

Honorable Mention: “Chocolate Galaxy”

An Afrofuturist hip hop opera made on a shoestring budget, this 20-minute film features eye-popping visuals and banging tunes.

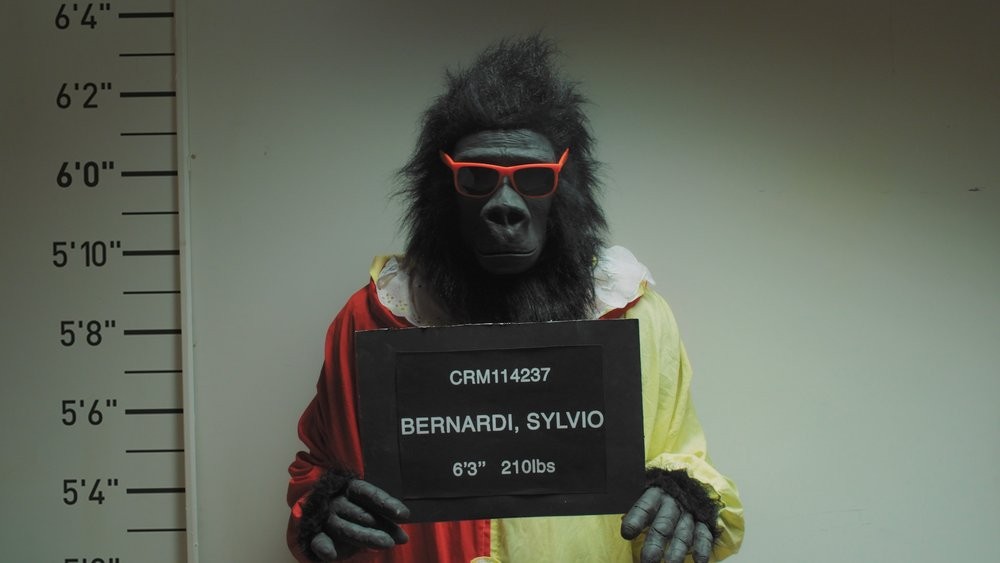

Best Performance by a Nonhuman:

Puppet Annette

This coveted award goes to Annette, Leos Carax’s gonzo musical collaboration with Sparks, which used a puppet to represent its namesake character, the neglected child of Adam Driver and Marion Cotillard, because they couldn’t find a newborn who could sing.

Medievalist: The Green Knight

To create one of the strangest films of 2021, all director David Lowery had to do was stick to the legend of Sir Gawain’s confrontation with a mysterious Christmas visitor to King Arthur’s court. Driven by Dev Patel’s pitch perfect performance, The Green Knight felt both completely surreal and strangely familiar.

Best Animation: Cryptozoo

Annette and The Green Knight were weird, but the year’s weirdest film was Dash Shaw’s exceedingly strange magnum opus. Think Jurassic Park, only instead of CGI dinosaurs it’s Sasquatch and unicorns drawn like a high schooler’s notebook doodles come to life.

Honorable Mention: The Mitchells vs. the Machines

Gravity Falls’ Mike Rianda pulls off the difficult assignment of making an animated film that appeals to both kids and adults with this cautionary tale of the connected age.

Best Performance: (tie) Kristen Stewart, Spencer; and Anna Cobb, We’re All Going to the World’s Fair

Both Stewart and Cobb played women trapped in nightmarish situations, trying to hold onto their sanity while watching their worlds crumble around them. For Stewart, it was Princess Diana’s last Christmas with the queen. For Cobb, it’s a teenager succumbing to an internet curse. The success of both pictures hinges on their central performances, but the difference is that Stewart’s one of the world’s highest paid actresses, and this is Cobb’s first time on camera.

MVP: Edgar Wright

Wright started the year with his first documentary, The Sparks Brothers, an obsessive ode to your favorite band’s favorite band. Sparks’ story is so strange and funny, and Wright’s style so manic and distinctive, that many viewers were surprised to learn it wasn’t a mockumentary. Then, he dropped Last Night in Soho, a humdinger of a Hitchcockian horror mystery which evoked the swinging London of the 1960s. Wright continues to deliver the most fun you can have in a multiplex.

Best Director: Steven Spielberg,

West Side Story

I feel like this Spielberg kid’s got potential. Hollywood’s wunderkind is now an elder statesman, but his adaptation of the Broadway classic proves he’s still got it. With unmatched virtuosity, he brings Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim’s songs to life and updates the story’s sensibilities for the 21st century. West Side Story stands among the master’s greatest work.

Best Documentary: Summer of Soul

The most transcendent on-screen moment of 2021 actually happened in 1969, when Mavis Staples and Mahalia Jackson duetted “Precious Lord” at the Harlem Cultural Festival. Questlove’s directorial debut gave the long-lost footage of the show the reverent treatment it deserves. Thanks to the indelible performances by the cream of Black musical talent, Summer of Soul was as electrifying as any Marvel super-fest.

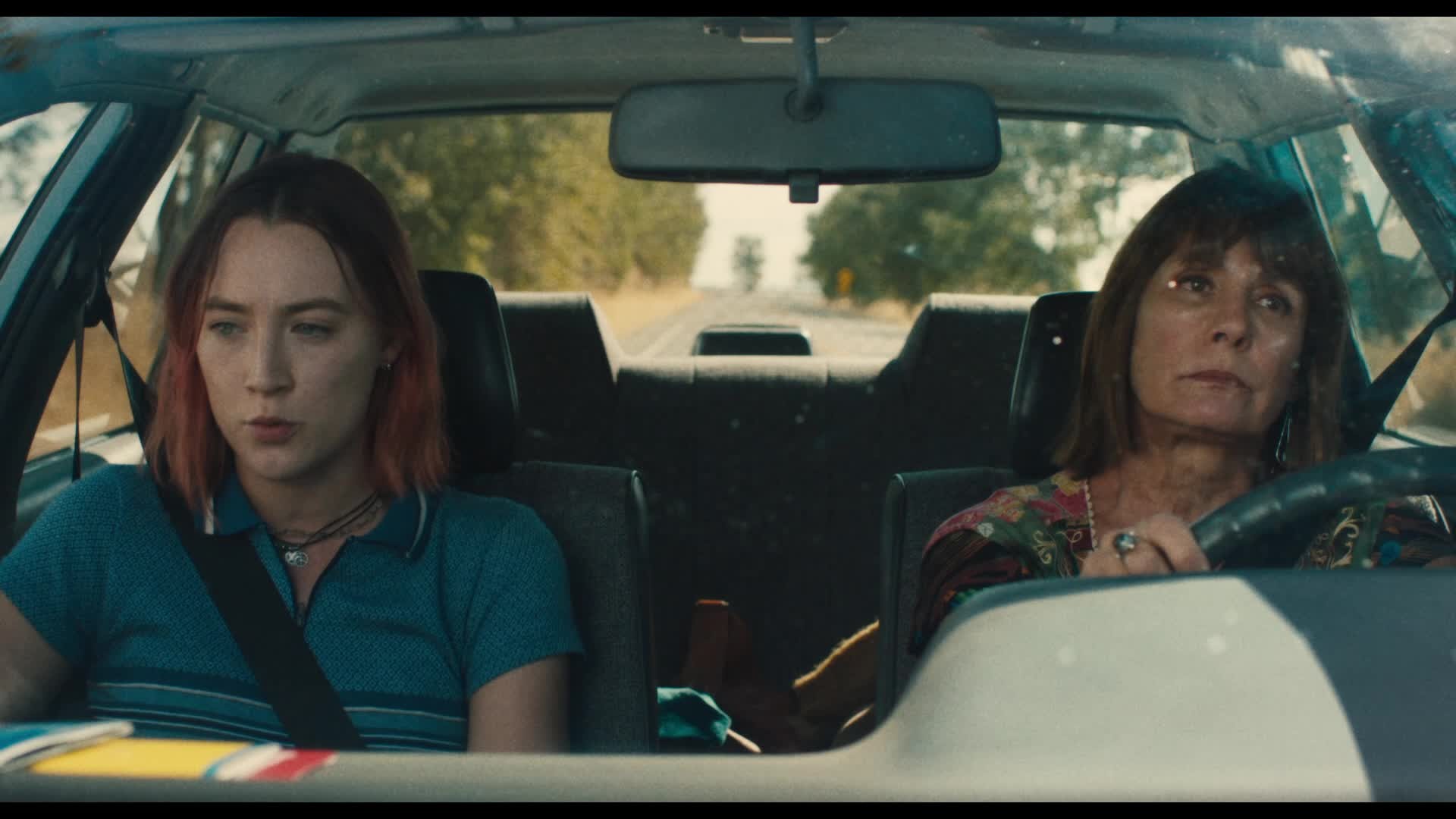

Best Picture: Zola

I can hear you now: “You’re telling me the best picture of 2021 was based on a Twitter thread by a part-time stripper from Detroit?” Hey, I’m as surprised as you are. But director Janicza Bravo turned a raw story of a road trip gone wrong into a noir-tinged shaggy-dog story of petty crime and unjust deserts. The ensemble cast of Taylour Paige, Nicholas Braun, Colman Domingo, and particularly Riley Keough is by far the year’s best, and Bravo shoots their ill-fated foray into the wilds of Tampa, Florida, like she’s Kubrick lensing A Clockwork Orange. Funny, self-aware, and unbearably tense, Zola is a masterpiece that deserves a bigger audience.