UPDATED: As is generally known, Memphis city elections are not subject to partisan voting. There are no primaries allowing our local Republicans and Democrats to nominate a candidate to carry the party banner.

Nor, in the case of citywide office (mayor or council super districts 8 and 9), does there exist machinery for a runoff election when no candidate for those offices commands a majority of the general election vote.

There are runoff circumstances for districts 1 through 7, each of them a single district contributing to the pastiche of city government, by electing, in effect, a council member to serve a smaller geographical area or neighborhood.

The aforementioned super districts encompass the entire city. Each of them, in theory, represents a half of the city’s population — the western half being predominantly Black, as of 1991, when the first super-district lines were drawn, the eastern half being largely white. (Though population has meanwhile shifted, those distinctions are still more or less accurate.)

Runoffs are prohibited in the super districts as well as in mayoral elections in the city at large because, in the Solomonic judgment of the late U.S. District Judge Jerome Turner, who devised this electoral system in response to citizen litigation, that’s how things should be divided in order to recognize demographic realities while at the same time discouraging efforts to exploit them.

Each citizen of Memphis gets to vote for four council members, one representing the single district of their residence, the other three representing the half of the city in which their race is predominant. Runoffs are permitted in the smaller single districts, where racial factors do not loom either divisive or decisive, while they are prohibited in the larger areas, where, in theory, voters of one race could rather easily league together to elect one of their own (as whites commonly did in the historic past).

Mayoral elections are winner-takes-all, and Willie Herenton’s victory in 1991 as the first elected Black mayor is regarded as having been a vindication of the system.

Got all that?

Yes, it’s a hodgepodge, but it’s what we’ve still got, even though Blacks, a minority then, are a majority now. And, in fact, race is irrelevant in the 2023 mayor’s race, there being no white candidate still participating with even a ghost of a chance of winning.

Political party is the major remaining “it” factor, and the failure of either party to call for primary voting in city elections has more or less nullified it as a direct determinant of the outcome.

But, with the withdrawal last week from the mayoral race of white Republican candidates Frank Colvett and George Flinn, speculation has become rampant as to who, among the nominal Democrats still in the race, might inherit the vote of the city’s Republicans.

Sheriff Floyd Bonner, whose law-and-order posture is expected to appeal to the city’s conservatives?

Downtown Memphis Commission CEO Paul Young, who has several prior Republican primary votes on his record in non-city elections?

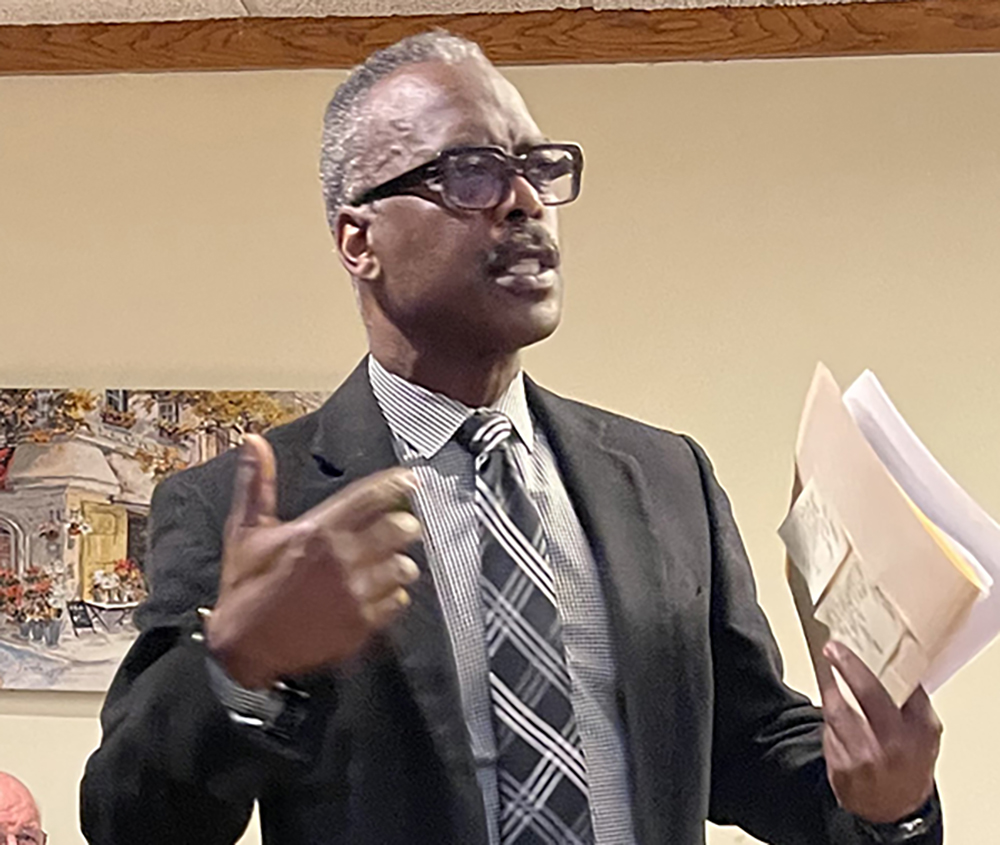

Businessman J.W. Gibson, who once was a member of the local Republican steering committee?

Only NAACP president Van Turner and former Mayor Herenton, among serious candidates, are exempt from such speculation, both regarded as being dyed-in-the-wool Democrats.

In a close election, the disposition of the Republican vote, estimated to be 24 percent of the total, could be crucial.