When I walk into Electraphonic Recording to meet Howard Grimes, I hear him before I see him. He’s behind the drum kit, recreating a beat he used to do when he backed a doo-wop group, the Largos, at Currie’s Club Tropicana. He’s laughing at the memory as he plays the shuffle he’d start when Roosevelt Green did his comedy bit. “He would pantomime this whole scheme, and it was all based on the rhythm I was playing. Boom-chick, boom-chick. The funniest part was when he got in his car, and he’d slam the door and I’d catch him — it was tight, man! — then he’d crank the car up, and you’d see him still moving and dancing inside as he drove away.”

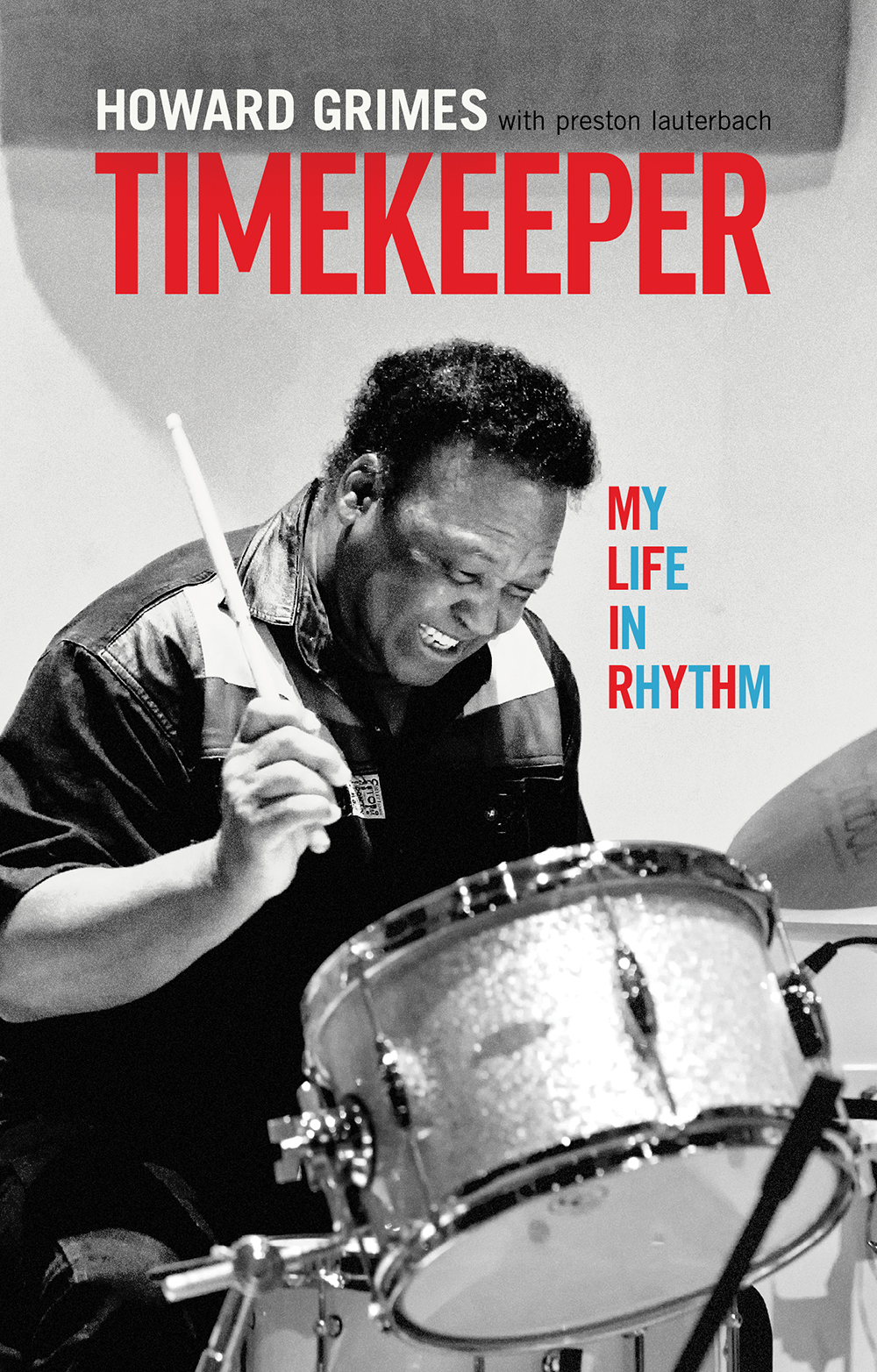

Club Tropicana is fresh on my mind, as I’ve just read Grimes’ new autobiography, Timekeeper: My Life in Rhythm (Devault Graves Books), written with Preston Lauterbach. Yet having it spring to life with his actual playing and stories from his youngest days feels like some kind of miracle. It makes one grateful to be around when legends like Grimes still walk the earth.

Reading the book, to its credit, is very much like hearing stories from the great man himself. Only the beats are missing, though you can listen along to the accompanying “Howard Grimes ‘Timekeeper’ Playlist” on Spotify. It presents hit after hit that Grimes played drums on, from Rufus and Carla Thomas’ “Cause I Love You,” a significant early single on Satellite Records (before it became Stax), to Willie Mitchell’s “Soul Serenade” from 1968, to the silky funk of Al Green’s greatest chart-toppers. Few figures span the transition from early ’60s R&B to the smooth, funky soul of the ’70s with such aplomb, but hearing the span of his work on the playlist as you read, a direct connection between the herky-jerky “Frog Stomp” and the smoldering “Love and Happiness” becomes apparent: a relentless, driving rhythm.

That driving, steady quality led Willie Mitchell to call him “Bulldog.” As Grimes recalls, “Willie Mitchell told me, ‘You know, Howard, when you play, I can hear you coming.’ I didn’t know what he was talking about. But when I cut a track, he said, ‘I can hear you coming. That foot!’ Willie was very distinct on listening to musicians. That’s how I learned so much.” The nickname has stuck to this day with variations. “Teenie [Hodges] always called me Pup. ‘Hey Pup, what ya doing, Pup?’ Leroy [Hodges] called me Dog. When I cut a session, Willie would always go, ‘Hey Dog! There’s the Dog! Here he comes!’”

Speaking of the many iconic tracks he laid down with the Hodges brothers and Mitchell, I can’t resist asking Grimes about one beat in particular, so distinctive as to have been subsequently sampled on nearly 200 tracks, from The Notorious B.I.G. to Massive Attack: the introduction to Al Green’s “I’m Glad You’re Mine.”

“Well, I love Ernie K-Doe and Lee Dorsey. So Lee Dorsey had this record out, ‘Working in the Coal Mine.’ The day ‘I’m Glad You’re Mine’ came up, I couldn’t hear nothing but that ‘Working in the Coal Mine’ pattern! So something guided me to play the first four bars of that because I knew it would fit with the way we had worked up the song. When we put the song together and we cut it, [Willie] said, ‘Man, you crazy as hell! Drummers ain’t never gonna figure out what the hell you did! Where in the hell did you come up with that?’ So I told him, and he said, ‘You just as crazy as Earl Palmer. You all is tit for tat.’”

Some rhythms that Grimes put on wax years ago mystify even him. “I cut a song on Ivory Joe Hunter, called ‘This Kind of Woman,’” he relates. “There’s no cymbals, just bongo drums and rhythm, and I don’t know what I did! It’s a difficult song, man, and I’ll be playing it now every day, trying to figure it out, could I ever bring that back? I haven’t figured it out yet.”

Howard Grimes and Preston Lauterbach will appear at the Stax Museum of American Soul Music, Live from Studio A, on Wednesday, July 21, 7 p.m. Live attendance is at capacity, but viewing by Zoom is offered at this link. The Bo-Keys will also perform with Grimes and singer Percy Wiggins. Free.