In a 1993 sketch on the short-lived The Ben Stiller Show entitled “30-Second Conspiracy Theory,” Bob Odenkirk sat on a park bench and muttered, “John F. Kennedy was assassinated for one reason only: because he was obsessed with the dream of mass producing an electric car. When the heads of the corporations of this country found out about his dream, they sent a lone gunman to Dallas. He drove there without stopping for gas because he was driving … an electric car.”

Questionable alliances between state politics and big business is indeed one reason for the rise and fall of the electric car in the 1990s, but the truth is less fantastic. As the competent and decent film Who Killed the Electric Car? argues, the only thing killed was the belief that a company always knows what is best for all of its consumers.

With the support of General Motors CEO Roger Smith, electric cars — called EV1s — were manufactured in the mid-1990s and leased to several consumers, particularly in California, where the state’s emission standards once required 10 percent of cars be zero-emission vehicles. The standards were never put into effect, however, and every EV1 was repossessed and either destroyed or hidden away in industrial back lots.

Chelsea Sexton, a former member of the EV1 design team, spends much of the film puncturing the GM representatives’ statements about the EV1’s poor sales and lack of consumer appeal. Actor Peter Horton was the last California resident whose EV1 was recalled. His face is a mask of steely disappointment as the car is toted away.

I wish the film had explored in greater detail this strong connection most people forge with their cars. The film begins with a mock funeral where the EV1 is praised as a “special friend,” an ironic statement that becomes more sincere as the film progresses and aerial photographs of rows of crushed EV1s linger like footage of military cemeteries. While Tom Hanks is joking in a clip when he tells David Letterman that he’s “saving the world” by driving an EV1, there is a palpable sense that conscientious consumerism is now one of the only ways left to express liberal principles.

The masterful counterstrike of the car companies, then, was to market the electric car as a harbinger of post-automotive doom. The film’s most revealing segment deals with these curious marketing strategies. One EV1 magazine ad features ghostly silhouettes against an abandoned playground blacktop, evoking creeping urban paranoia and social collapse. The images would have been more effective as photo supplements for The Grapes of Wrath instead of two-page inserts in Sports Illustrated. The unwillingness of GM and others to abandon the massive profits of gasoline and the internal combustion engine is apparent. Such ads clearly played a role in making the EV1 “unpopular,” and thus short-circuiting a laudable transportation alternative. As the optimistic finale points out, though, improved technology and consumer demand may resurrect a similar vehicle soon. So the electric car, like The Ben Stiller Show, may find an appreciative audience after all.

Who Killed the Electric Car?

Opens Friday, August 11th

Studio on the Square

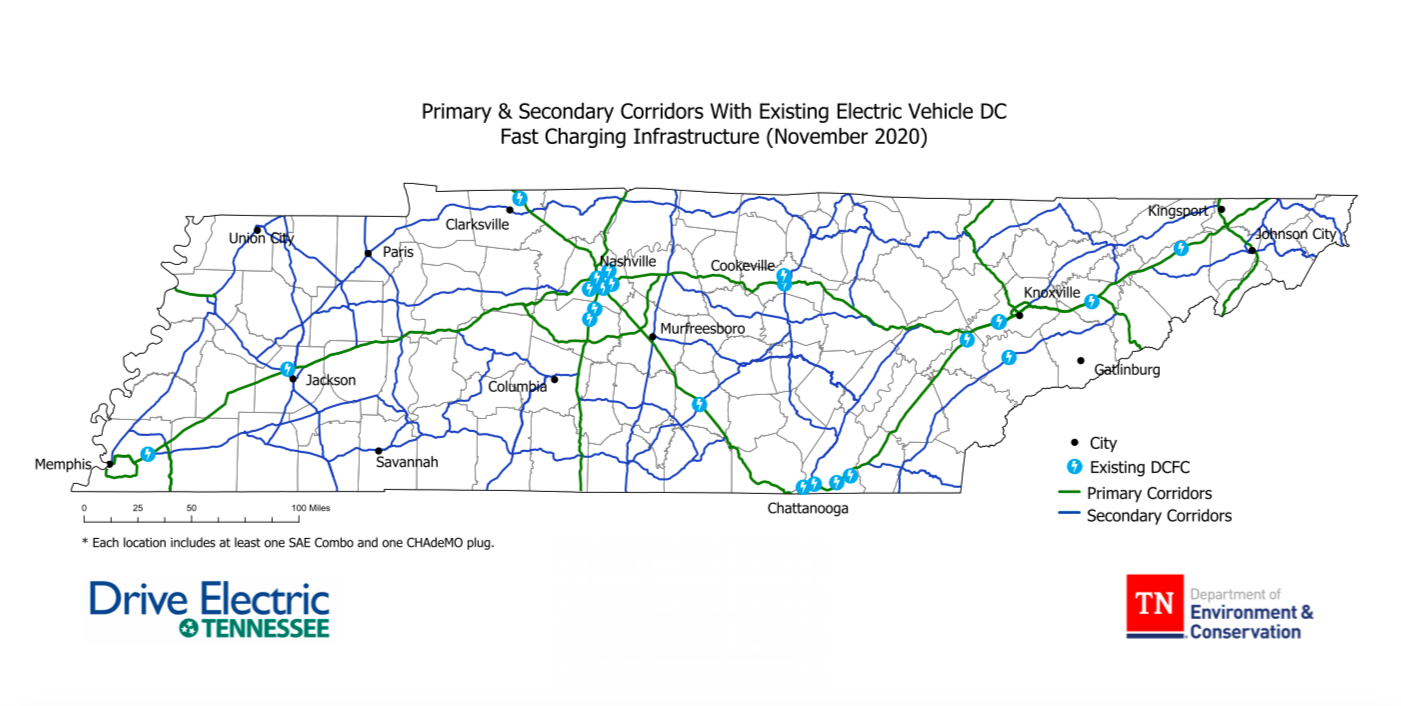

Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation

Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation  Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation

Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation