At least six elephants are visible from my place on the grassy hilltop. Three are off in the distance, partially hidden behind the branches of barren winter trees. They look like tiny dots. But three others are less than a mile from my safe spot behind a steel fence. They’re massive, but they appear harmless, almost like giant gray cows grazing in a pasture. One even appears to be smiling, the corners of her mouth turned up in a slight grin.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Carol Buckley looks over the 2,700-acre Elephant Sanctuary

I’m at the Elephant Sanctuary in Hohenwald, Tennessee, about 80 miles south of Nashville. Over 2,700 acres in Hohenwald are off-limits to humans, with the exception of a handful of elephant caregivers. The land is home to 18 female elephants, all retired from years in the circus or in zoos.

Many can probably balance on a platform, bow, or perform other unnatural circus tricks, but there’s none of that here. Executive director and co-founder Carol Buckley, herself retired from circus work, has seen firsthand the abusive training methods used by many circuses and the crowded conditions at zoos. Now she wants elephants to have a place to feel free from human control.

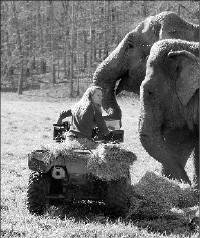

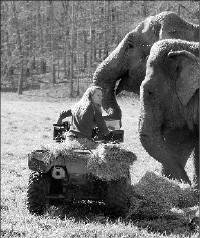

The elephants here at the country’s largest elephant sanctuary are free to roam the valleys, hills, and grassy pastures. They eat when they want, sleep when they want, and they’re never on exhibit. In fact, the public isn’t allowed into the sanctuary. Only staff, interns, volunteers, and the occasional reporter and photographer are allowed on-site. On our visit, I wasn’t allowed to go past the fence for a closer look. Photographer Justin Fox Burks was escorted through the sanctuary on the back of Buckley’s four-wheeler.

Our trip was in response to the fact that there has been so much written in recent years about elephant populations around the world undergoing a kind of species-wide trauma. Attacks on humans have increased dramatically in the wild. From an October 2006 New York Times Magazine article: “Decades of poaching and culling and habitat loss … have so disrupted the intricate web of familial and societal relations by which young elephants have traditionally been raised in the wild … that what we are now witnessing is nothing less than a precipitous collapse of elephant culture.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

” … [B]efitting of an animal with such a highly developed sensibility, a deep-rooted sense of family and, yes, such a good long-term memory, the elephant is not going out quietly. It is not leaving without making some kind of statement, one to which scientists from a variety of disciplines, including human psychology, are now beginning to pay close attention.”

Two’s a Crowd

Now the elephant debate has come to Tennessee. The natural, open fields of Hohenwald provide a stark contrast to the scene at the Memphis Zoo, where two female African elephants spend their days in an exhibit a little smaller than a football field. But plans are under way to give 22-year-old Asali and 43-year-old Ty a little more space by expanding into the nearby rhinoceros pen.

In the long term, zoo officials hope to build a much larger elephant space near the current site of the Northwest Passage, the zoo’s recent expansion project for polar bears and other arctic animals. Mammal curator Matt Thompson says they’d eventually like to add two more elephants.

The zoo’s plans mirror those of about 40 other zoos around the country that are expanding elephant space as more critics of elephant exhibits speak out. But a handful of zoos, in cities like Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, and the Bronx, are going a step further and closing their exhibits and donating elephants to larger zoos or sanctuaries or phasing them out as old elephants die off. It’s something Buckley would like to see happen at every zoo.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

“Those zoos are taking a giant step in saying that science supports that you cannot keep elephants in the traditional captive environments,” says Buckley, who lives on the sanctuary site, caring for the elephants as part of her daily routine.

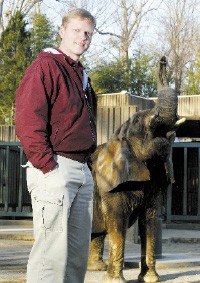

“We didn’t give any thought to [closing our exhibit],” according to Matt Thompson, who says the elephants are his favorite animal. “We’re very proud of our program. By all accounts, our elephants appear happy and healthy. I wish we had 20 of them. I wish we had 10 acres.”

The vibrant, young Asali is standing on one end of the Memphis Zoo’s elephant exhibit on a breezy Tuesday morning. Ty — older, larger, and sporting weathered skin — stands on the opposite end. Asali starts to move toward Ty, lifting her trunk as she lumbers toward her majestic elder. Ty also begins walking and as the pair nears one another, they slap trunks in what appears to be an elephant version of the low-five.

After the greeting, each elephant turns and slowly heads back to their respective sides. Ty takes a moment to punch a tire suspended from a wooden post using her trunk before heading back to her pile of hay. Playing and eating, Thompson tells me, are the way Asali and Ty spend their days.

“Zoos, in my opinion, are a necessary evil,” he says. “I wish elephants didn’t have to be kept in captivity, but unfortunately a lot of them do. Asian elephants are in big-time trouble in their native habitat, which is all but gone. We could easily see Asian elephants go extinct in our lifetime. That leaves zoos and sanctuaries to continue the species.”

Recent reports estimate that only about 60,000 Asian elephants are left, but Buckley says captive breeding isn’t the answer.

“Breeding in the U.S. has nothing to do with helping the species in the wild,” says Buckley. She points out that there’s actually a surplus of captive elephants in Asia, a result of government deforestation. (Elephants once assisted humans with logging.)

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

The Divas (Billie, Liz and Frieda)

But Memphis’ elephants aren’t Asian, they’re African, and Thompson believes that species is also in danger. He says African pachyderms are sometimes poached for their ivory, and a recent spike in elephant populations in South Africa has reopened a debate over culling, the once-legal practice of killing elephants to thin populations. The practice was outlawed in 1994, and elephant numbers rose dramatically.

Buckley believes the possibility of legal culling is not a threat due to a vast public outcry against the practice. She points out that a surge in elephant populations in Africa is more noticeable because so many of that continent’s elephants are confined to national parks due to habitat loss. If they had more wild space, they would spread out.

The Memphis Zoo is attempting to breed Asali. She was artificially inseminated last month, but zoo officials won’t know if she’s pregnant for a few more months. If she is, it’ll be 22 more months before the baby elephant is born.

“It takes a long time to cook a 300-pound baby,” says Thompson, chuckling.

The zoo hopes to begin expanding the elephant barn, the area where Asali and Ty sleep on cold winter nights, later this year. The expansion into the rhino space, located next door to the elephants, probably won’t happen until the rhino living there either dies or is moved to a new space. Thompson calls the rhino “geriatric” and says she’s already lived past her life expectancy.

The planned elephant exhibit near the Northwest Passage won’t come to fruition until around 2012. No plans have been drawn up detailing just how much more room the elephants will have in the new exhibit, but it will probably exceed the Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ standards: 1,800 square feet of outdoor space for one elephant and 400 square feet of indoor space. To get an idea of the size of the spaces, consider that a football field is 57,600 square feet.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Buckley at feeding time

When the multimillion-dollar expansion is complete, Thompson says they’ll add two more elephants, one male and one female. The new elephants would be rotated between the new exhibit and the current one.

“We’ll interchange them. We’ll walk them back and forth so they can get exercise,” says Thompson. “We may even make moving the elephants something for people to watch.”

That’ll be more exercise than Asali and Ty have had in years. For now, their only workout involves walking from one end of their pen to the other.

Back in 1997, the Memphis Zoo made a commitment to elephants, according to Thompson. They decided to keep the exhibit open rather than phase it out. But to do so, zoo officials knew they’d have to improve their elephant program.

At that time, they switched to “protected contact,” a method of dealing with elephants without entering their space. Zookeepers trim the elephants’ feet, bathe them, draw blood, and do other medical procedures from behind a steel fence. Previously, keepers would go inside the exhibit.

“When we stay outside the bars, there’s a whole trust thing going on,” says Thompson. “It works like this: If they do something for us, they get a treat. Elephants are chowhounds. They love treats, so they’re very cooperative.”

About four years ago, the exhibit was expanded into an adjacent space in between the elephant and rhino exhibits. That space was once home to tapirs, a large mammal that resembles a pig crossed with an anteater, but the tapirs were donated to another zoo. Last year, the zoo added an 80,000-gallon wading pool.

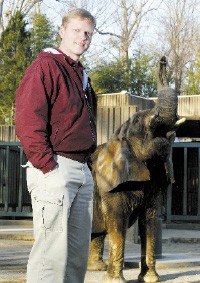

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Matt Thompson

Eighteen’s Not Really a Crowd

Billie, Liz, and Frieda, also known as the Divas, are a little timid this morning. From our place on the hill, Buckley tells me they’re fairly new to the Elephant Sanctuary. They came from the Hawthorne Corporation, a circus training farm charged with 47 counts of animal abuse in 2003.

Nine of those elephants were given to the sanctuary, and several adjusted quickly. But these three are taking their time. They stick close to the state-of-the-art heated barn where elephants sleep on cold nights.

While Buckley and I talk, a caretaker approaches the Divas on a four-wheeler, and Buckley yells for her to open a gate near the elephants. The worker is no more than 10 feet from the colossal creatures. Both human and pachyderms appear at ease.

Though Billie and Frieda were labeled “dangerous” by the circus crew, Buckley says they’ve shown nothing but affection since they’ve been at the sanctuary. Elephants here are generally managed with “free contact,” meaning caretakers go where they are.

“Between 7 and 9 a.m., we go out on our four-wheeler and give them their supplemental feedings, which includes grain, produce, and hay,” says Buckley. “They’re wide awake at that time, usually foraging.”

Though the sanctuary is still a form of captivity, the area resembles the wild, and, believe it or not, the climate in rural Tennessee is quite similar to the subtropical southeastern Asian climate these elephants would experience at home. Though only 18 inhabit the space for now, Buckley says 100 elephants could live at the sanctuary comfortably.

“The only way I believe you can do right by a captive animal is to ensure they are living in an environment with all of the same components that they would have in the wild,” says Buckley. “Here at the sanctuary, it’s captivity. But we’re taking a more serious look at how we do what we do.”

Having worked in zoos and circuses for years, Buckley knows a thing or two about captive environments. She realized that the animals weren’t happy in cramped quarters or abusive situations, so she and co-founder Scott Blais bought 220 acres of land and started the sanctuary in 1995. It has since seen several expansions.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Asali and Ty at the Memphis Zoo

She’s glad to see some zoos opt to close their exhibits, but the elephant-space expansion going on at other zoos, including the Memphis Zoo, concerns her.

“It’s a Band-Aid. It’s not a solution,” says Buckley. “Many zoos will spend a pile of money making the yard twice as large, but that makes no difference for elephants. They will continue to suffer.”

Gay Bradshaw, an animal-psychology researcher at Oregon State University, agrees. She’s been working with the sanctuary, studying post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in elephants.

“Some might say elephants need more space, but that’s not all. They need to have something like the [Elephant Sanctuary],” says Bradshaw via phone. “Yes, that’s captivity, but it’s a kind of captivity where an elephant can be an elephant. They can do what they want when they want. A nice physical space is not enough.”

Research like Bradshaw’s, which claims that traumatic events can cause mental illness in elephants, is proving that elephants are more self-aware than previously thought. In October, researchers at the Bronx Zoo discovered that elephants recognize themselves in a mirror, a complex behavior only previously found in humans, chimpanzees, and dolphins.

Like humans, elephants have a tight-knit family structure. They bury their dead with earth and brush and conduct vigils at gravesites. At the sanctuary, elephants Sissy and Winkie kept a three-day vigil at the grave of their pal Tina. At the end of the vigil, Sissy left her favorite toy, a tire she’d frequently carried around with her trunk, on Tina’s grave, as if it were a bouquet of fresh flowers.

Elephants Never Forget

Last summer, Winkie, a 40-year-old, 7,600-pound elephant at the sanctuary, lashed out unexpectedly, killing her 36-year-old caretaker, Joanna Burke.

The incident happened while Burke and operational director Blais were conducting a routine inspection of Winkie to check for bites or wounds. They noticed her right eyelid was a little swollen, perhaps from a bug bite or sting.

Blais performed a close examination of the eye, and Burke offered the elephant some water. As Burke moved to Winkie’s right side to get a closer look at the eye, the elephant suddenly struck Burke across the chest and face with her trunk. The blow sent Burke flying to the ground, and Winkie stepped on her, killing her instantly. When Blais tried to intervene, Winkie attacked him, fracturing a bone in his leg. After the killing, Winkie acted withdrawn for weeks, as if she was mourning her caretaker’s loss.

Though Winkie had never killed before, she did have a bad reputation before arriving at the sanctuary from the Henry Vilas Zoo in Madison, Wisconsin. Since Winkie had arrived at the sanctuary, they’d had no problems with her.

Bradshaw believes Winkie has a classic case of PTSD. She’s working with the sanctuary on healing Winkie as well as two other elephants believed to be experiencing signs of trauma. She believes the stress spawns from seeing their families killed when they were taken into captivity as baby elephants or from abusive situations in circuses and zoos.

“In Africa, when bringing the elephants into captivity, a number of elephants are orphaned from culls. That affects the neurobiology and behavior of a baby. Trauma becomes etched on the brain,” says Bradshaw. “In Asia, they didn’t cull, but they do capture babies and take them into captivity.”

Thompson, of the Memphis Zoo, says he isn’t familiar with Bradshaw’s research but he does believe elephants can suffer from PTSD. Ty, the zoo’s older elephant, came from the Ringling Brothers Circus when she was 12 years old.

“They were probably pretty rough on her. The circus in 1974 wasn’t a pleasant place to be if you were an elephant,” says Thompson. “To this day, she doesn’t like it when people raise their voice.”

With all the new research coming out, Buckley wishes more zoos would take note and close their elephant exhibits. “The elephants who come to us are in the very worst situations,” she says. “They’re the ones that zoos and circuses want to get rid of. We’re the dumping ground, which is fine. But we would love to see all elephants in a better situation.”

In an effort to educate the public about the sanctuary’s program, plans are in the works for an educational center. The center would give the public a chance to visit the sanctuary without disturbing the elephants. Views of the elephants would be available through video feed from cameras placed throughout the habitat.

“People can come and learn about our philosophy of non-dominance and non-intrusion,” says Buckley. “It’ll give people a physical place to come to because they’re used to that, yet they will not be looking at the elephants eye-to-eye.”

“We’re in a new paradigm, a trans-species paradigm,” says Bradshaw. “We have a stellar model by which elephants in captivity can be supported and healed. That’s the Elephant Sanctuary. The science is there. It’s not just an animal-rights issue. It’s time to make a shift.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks