Don’t make the mistake of categorizing 19th- and 20th-century Southern women artists as mainly genteel painters of magnolias. Not that there’s anything wrong with such endeavors, but to imagine the ladies doing no more than amusing themselves for an afternoon with easel and palette is to misjudge their impact.

The proof hangs at the Dixon Gallery and Gardens, where “Central to Their Lives: Southern Women Artists in the Johnson Collection” and works by Kate Freeman Clark are on display. This series — which includes works by Memphis artist Elizabeth Alley — examines women artists from the 1890s to the present.

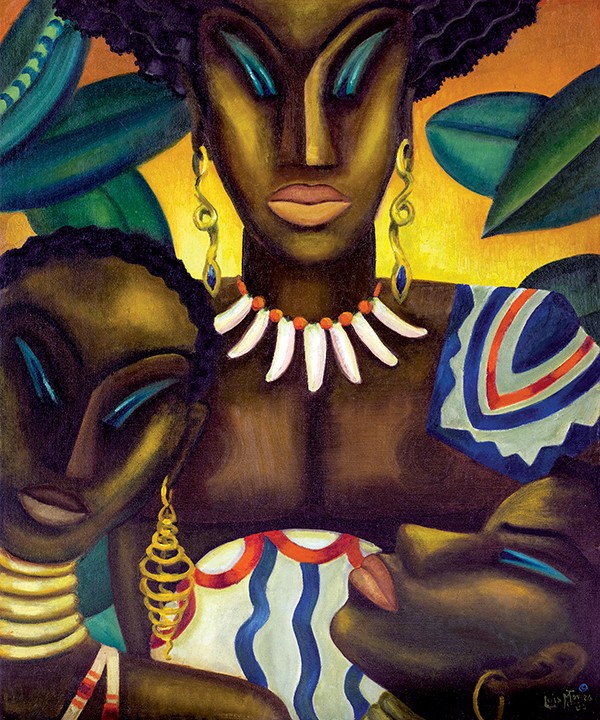

Africa, 1935.Loïs Mailou Jones

Julie Pierotti, curator at the Dixon, points out that, “It’s not necessarily Southern women artists painting the South. They lived and traveled just like everybody else, and they painted what they experienced. Sometimes Southern women artists left the South permanently and went to New York and California and Colorado — different places — and planted themselves there. But of course we still consider them Southern or having a Southern sensibility.”

The Johnson Collection of 42 women artists covers work from the late 1890s to the early 1960s. As the text for the exhibition notes, “Women’s social, cultural, and political roles were being redefined and reinterpreted.” Clark, from Holly Springs, Mississippi, has art in the Johnson Collection, but the Dixon wanted to showcase her particular story in a companion exhibition of nearly 40 works.

“We’re showing people in the larger survey of Southern women artists and then this super-specialized exhibition of someone so close to us,” Pierotti says. “Clark is a good example of an artist from the South, from this old Holly Springs family.” She wanted to go to New York to study art, enrolled in the Art Students League in 1895, and soon found a mentor in William Merritt Chase, the acclaimed artist and teacher. She was closely shadowed by her mother and grandmother as escorts. “Many of the figure paintings in this show are of them or people who were close to her,” Pierotti says. “Her mother and grandmother were supportive of her painting but not of her exhibiting or selling her work. Selling wasn’t a respectable thing to do.” On the rare occasions she showed, she signed the paintings as Freeman Clark to obscure her gender.

So she wasn’t acknowledged in her time, although Chase thought a lot of her work. Clark was influenced by the Impressionists, and worked with “a good grasp and clear understanding of how to communicate light and shadow,” Pierotti says.

There are paintings of gardens, which are thoroughly planned out, and the work is linear and brushwork tight. But then she’d do unfettered landscapes with a looser brush and sometimes on burlap. “As a Southerner, she understood that kind of rustic nature of rural landscapes,” says Pierotti.

Chase died in 1916, and Clark’s grandmother died in 1919 and her mother in 1922. She then went back to Holly Springs, leaving her passion behind forever. Her works were kept in a warehouse in New York until her death in 1957 at age 81. But she willed hundreds of her pieces to Holly Springs, along with her house and money, to build what is now the Kate Freeman Clark Museum.

“The museum is her champion,” Pierotti says, “and it has done a good job maintaining the work. They’re promoting it, and the Johnson Collection has also backed her work. We’re trying to put some scholarship behind her work with a serious discussion of her technique. As often happens, especially with female artists, we’re in this period of discovery of many of these women whose stories really haven’t been told.”

“Central to Their Lives: Southern Women Artists in the Johnson Collection” and works by Kate Freeman Clark are on display through October 13th at the Dixon Gallery and Gardens.