The once — and seemingly future — gravesite of General Nathan Bedford Forrest and his wife is on a promontory at Elmwood Cemetery called Chapel Hill. Dominated at its apex by a statue of Jesus, the hill slopes down on its western side to a grassy area containing several graves adorned with the name “Forrest,” — four of them in a row belonging to his brothers, all of whom, according to the stones’ modest inscriptions, served as cavalry officers for the Confederate States of America.

In front of these modest markers is a plain grassy area that appears vacant and undisturbed — but that is somewhat misleading, for this earth has been turned more than once, the last time, some 110 years ago, in 1905, so that General Forrest and his wife, Mary, could be disinterred and reburied a mile and a half north, under a splendid bronze statue of the general on horseback. And there it has remained, the centerpiece of an urban park named for a man who was regarded for many decades as a local hero of heroes: Nathan Bedford Forrest, whose military tactics are so highly regarded that they are taught at West Point, whose exploits were countless, and whose valor was marked by the many horses that were shot out from under him in battle.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

The Forrests would occupy the space in front of the general’s brothers at Elmwood Cemetery.

A month ago, during the whiplash of worldwide revulsion that followed the gunning down in Charleston, South Carolina, of nine African Americans engaged in bible study by a delusional white youth who embraced Confederate imagery, the rebel battle flag began being hauled down from its official places everywhere, as a symbol of an idea whose time had not only come and gone but had clearly become toxic.

And, as Southerners, dazed and horrified by the tragedy like everyone else, looked closer at a venerated Confederate heritage they had long taken for granted, it began to dawn on many that the poison may always have been there. As they read the published manifestoes of the secessionist states, one after another of them proclaiming as their casus belli the need to defend white supremacy and the God-given right to subjugate blacks, the rhetoric of those forefathers could not be cleanly disentangled from the recent ravings of the lunatic Dylann Roof.

Nor could absolution from the legacy of this racial hubris be conferred on the persona of General Forrest — a slave trader before the war, a commander accused during the war of responsibility for the massacre of black Union troops trying to surrender at Fort Pillow, and the documented founder and first Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan after the war.

All this was hard to explain away, although the general’s defenders certainly tried, as the Memphis statue increasingly became a provocation — not only to the city’s African-American population, now a political majority, but to business interests and civic-minded folk who saw the official veneration of Forrest as an embarrassment and a hindrance to civic progress.

Mayor A C Wharton responded to the outrage in Charleston by calling for the expedited removal of the statue and gravesites from what was now called Health Sciences Park. It was the culmination of a process that had long been building.

• Anti-Confederate sentiment first flared in Memphis in earnest in 2005. The Forrest statue was directly assailed by a group of African-American dignitaries, including Shelby County Commissioner Walter Bailey and the Rev. LaSimba Gray, while the Center City Commission (now the Downtown Memphis Commission) petitioned the City Council to consider renaming not only Forrest Park but Jefferson Davis Park and Confederate Park downtown.

Influential businessman Karl Schledwitz, a trustee of the University of Tennessee, whose medical-school buildings surround the park property, made the first proposal for an outright removal of the statue and the return of the Forrests’ remains to Elmwood Cemetery. City Councilman Myron Lowery made a more modest suggestion to add a monument to Ida B. Wells and perhaps other heroic black figures and to give the park a different name.

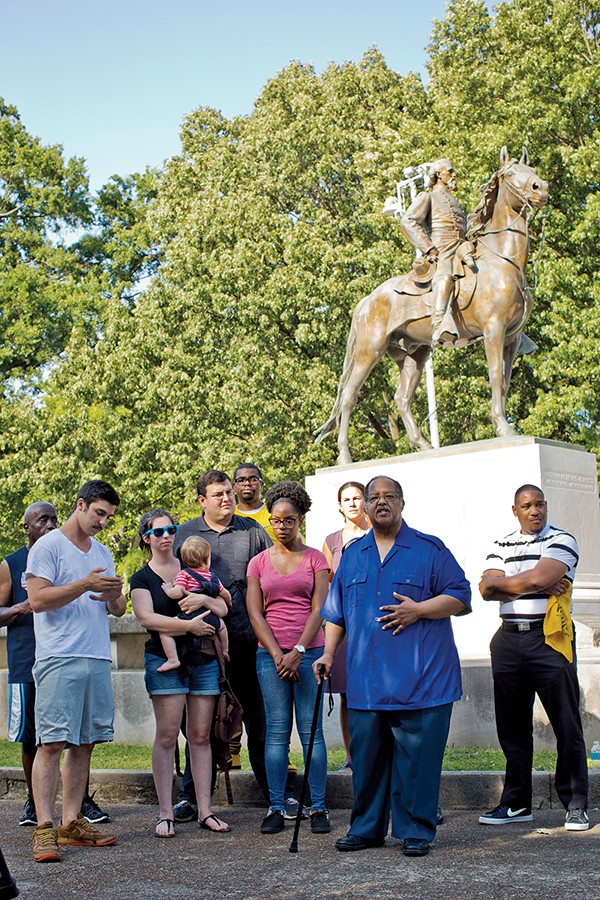

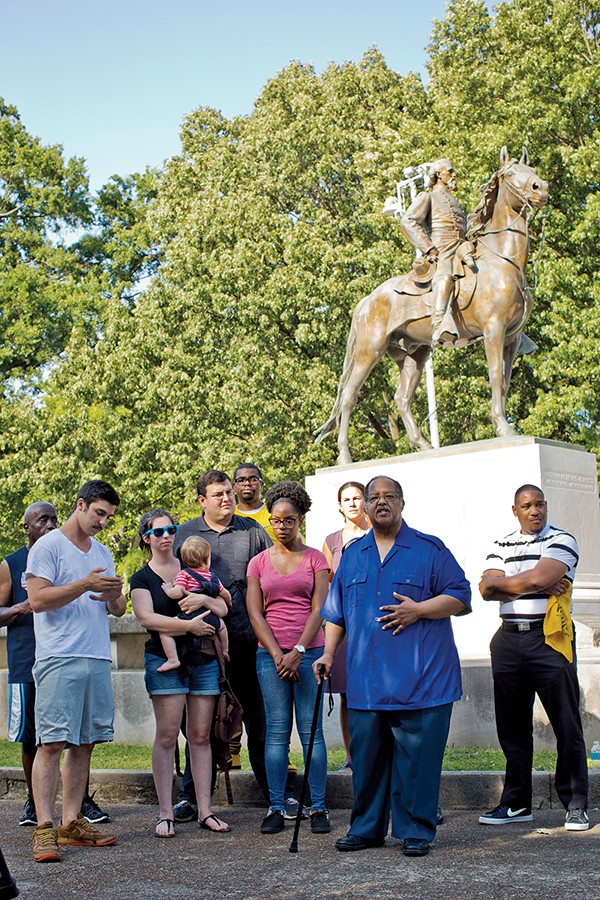

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Myron Lowery and youthful demonstrators at the general’s statue last week.

In the middle of all this ferment, the Rev. Al Sharpton came down to add his two cents. But then Mayor Willie Herenton held a news conference to denounce “outside agitators” and scotch what he considered the wild talk of name changes and tampering with monuments. The mayor did propose transferring maintenance of Forrest Park to UT, however, and, after all the fuss, that change was made.

Further defusing the situation had been advice from then state Senator Steve Cohen. Minutes of the climactic meeting of the Center City Commission in 2005 record Cohen’s position this way: “There have been things that have offended him as a minority, but he has learned to overcome those personal offenses and see things in a bigger light. … He asked for the board to reconsider this issue and not pass it forward, for it will do no good and will only do harm.”

In the end, the then Center City Commission’s resolution for name changes of the downtown parks, spearheaded by then chairman Rickey Peete and board member (later director) Paul Morris, was ignored by the council, as well as by the Chamber of Commerce, the Landmarks Commission, and the Convention & Visitors Bureau. Even Bailey would say, “I think we’re at a point where until such time as we see some concern by our city leaders, we have to continue to pause.”

An extended pause did ensue, during which, in 2009, over objections from Bailey, state Representative G.A. Hardaway, and others locally, Forrest Park was added to the National Register of Historic Places. That was something of a coup for N.B. Forrest Camp 215, the local unit of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, which had submitted the nomination to the National Register and which had been assisting in routine maintenance of the park for years.

• Things had cooled off and settled into something of a détente between contending parties until 2011, when the Sons of Confederate Veterans, confident that the moment of danger had passed, arguably overplayed their hand.

Lee Millar, an officer of N.B. Forest Camp 215, had written a letter to Cindy Buchanan, then city parks director, proposing to place a new sign with the name “Forrest Park” on the Union Avenue side of the park. Millar had signed his letter, however, not as an officer of the Sons of Confederate Veterans but as chairman of the Shelby County Historical Commission, a post he held at the time.

Buchanan responded with a letter that said, in part, “We appreciate the commission’s offer to provide this important signage for one of the city’s historic parks. … The proposal to create a low monument style sign of Tennessee granite with the park name carved in the front was reviewed by park design staff and found to be appropriate in concept … similar to the monument style signage placed by the city at Overton Park.”

The letter directed Millar to meet with Mike Flowers, administrator of park planning and development, to follow through on the construction and installation of the sign. Copies of Buchanan’s letter were apparently sent to Flowers and then city CAO George Little.

That is as far as the process went, when N.B. Forrest Camp 215 (not the Shelby County Historical Commission), apparently acting on the strength of Buchanan’s letter and dispensing with the suggested further meeting with city officials, raised $9,000 — enough to pay for a large granite sign saying “FORREST PARK.”

The sign sat there for some weeks until its presence was brought to the attention of Little, who insisted that the sign was unauthorized — as, from his point of view, it was: no city permit having been issued.

Little had the sign removed early in 2013, and the simmering crisis was reignited. It was fired up even further when, amid a new groundswell for changing the names of the three Confederate-tinged downtown parks, two state legislators — state Representative Steve McDaniel of Parkers Crossroads and state Senator Bill Ketron of Murfreesboro — rushed into passage HB553, a bill declaring that “[n]o statue, monument, memorial, nameplate, or plaque which has been erected for, or named or dedicated in honor of …” [the bill then names a seemingly complete list of America’s wars, including the Civil War] “… located on public property, may be relocated, removed, altered, renamed, rededicated, or otherwise disturbed.”

The bill went even further, prohibiting name changes to any “statue, monument, memorial, nameplate, plaque, historic flag display, school, street, bridge, building, park preserve, or reserve which has been erected for, or named or dedicated in honor of, any historical military figure, historical military event, military organization, or military unit” on public property.

Though the bill created obstacles to altering the status of the general’s statue and the downtown parks and provided grounds for litigation that still exist, it also inflamed sentiment on the Memphis City Council, which saw this maneuver as an outright transgression by the legislature against local sovereignty. The council’s reaction was further stoked by counsel Allan Wade’s statement that McDaniel and Ketron had been acting on a suggestion by Millar.

Councilman Shea Flinn referred to “the ironic war of aggression from our northern neighbor in Nashville,” while Councilman Harold Collins said, “We will never let the legislature in Nashville control what we in Memphis will do for ourselves.”

Thereupon the council, hesitant to act in 2005, voted 10-0, with three abstentions, for name changes in three downtown parks: Forrest Park would become Health Sciences Park; Jefferson Davis Park would become Mississippi River Park; and Confederate Park was renamed Memphis Park.

And there matters stood until the awful events in Charlleston June 17th.

• Wharton’s demand for the removal of the statue and graves from what was now Health Sciences Park followed quickly upon the atrocity, and council chairman Lowery’s authorship of a resolution to return the remains to Elmwood and an ordinance to remove the statue was announced almost immediately afterward. Unlike the cases of 2005 and 2013, there was no hint of a contrary view on the council.

A quantum leap in consciousness had occurred in Memphis, as elsewhere. In South Carolina, Governor Nikki Haley and a suddenly compliant legislature agreed to lower the capitol’s ceremonial Confederate battle flag. In Mississippi, official action was begun to remove Confederate imagery from that state’s flag.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

A protestor taunts a Forrest loyalist.

On July 7th, Lowery’s proposals were approved unanimously by the council.

The issue was spoken to succinctly on that Tuesday night by, of all people, Bill Boyd, the venerable survivor of the old white-tinted South Side who can, as he did that night, cite the fact that Marcus Winchester, the first Mayor of Memphis, was his great-grandfather, and who had offered words of praise for Forrest in the parks-naming debate of 2013.

Defenders of Forrest, a handful of whom testified before the council, deny Forrest’s complicity in the massacre of surrendering black Union troops at Fort Pillow in 1864, and maintain that the general was not really the founder of the Ku Klux Klan. Or that, if he was, it was not a viciously intended organization with racist terror at its core. Or that, if other sorts allowed it to become that, Forrest expeditiously dissociated himself from it. Or whatever.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Children wonder what all the fuss is about.

Boyd made allowance for all these attempted exculpations in his remarks, but, as he noted, they all ignored the one fact of Forrest’s life that was undeniable: that he made his living before the war as a slave trader. That was something Forrest did of his own free will, for personal gain, said Boyd. Slavery was the stain on him, it was the stain on the Confederacy, and there was no defending it. And that was why Boyd was willing to see the general’s statue and remains removed from a place of official honor in downtown Memphis.

And that is why city government and state government and regional and national sentiment, across ideological and party lines, are all moving so deliberately and definitively to distance themselves from the likes of General Forrest and the whole panoply of the Confederacy — that once vaunted “heritage” now seen as a cover for what had been racial despotism.

• Not everywhere and by everyone, however. As the fates would have it, General Forrest’s birthday celebration occurred on schedule this past Sunday, with a formidable and impressive display of Confederate colors and a large and devoted crowd of celebrants. The turnout dwarfed a modest demonstration of youthful anti-Forrest protesters held earlier in the week.

Ironically, a proclamation in General Forrest’s honor from Governor Bill Haslam was read to the appreciative crowd. State law requires such a thing, Forrest’s birthday being one of six recognized state holidays. The governor, who has since advocated the removal of a bust of General Forrest from the state capitol, had penned the required accolade in early June, pre-Charleston.

The keynote speaker at Sunday’s celebration was one Ron Sydnor, an African American from Kentucky who serves as superintendent of Jefferson Davis State Historic Site there. He spent an hour providing biographical details about Davis, concluding with a story involving a congenial time spent together by the Confederate president and the “wizard of the saddle,” then a city alderman and, like Davis, involved in the insurance business in Memphis.

After Sydnor’s address, which was warmly applauded, came the ceremonial laying of wreaths at the base of the Forrest statue and a musket salute to the general by members of “the 17th Mississippi and 51st Tennessee Infantry, C.S.A.”

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

The general’s supporters at his birthday celebration Sunday.

But clearly, as they say, events are now in the saddle, despite the efforts of Forrest’s defenders, who have included esteemed deceased Memphis novelist/historian Shelby Foote, who in his monumental trilogy, The Civil War, lionized Forrest and discounted tales of his misconduct at Fort Pillow. If and when Nathan Bedford Forrest comes to rest again in his family plot at Elmwood Cemetery, he and his wife, Mary, will be reburied in their old vacated spot, immediately to the right of the graves of Foote and his wife.

The writer, as renowned a chronicler as Forrest was a warrior, was given his pick of sites at Elmwood, and this is the spot he chose.

That is one last tribute that, come what may, cannot be taken away from the general.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker