Midnight Movie

April 2014, Clarksdale, Mississippi — Filmmaker Mike McCarthy stands inside an old movie theater, shooting a scene he describes as “the death of cinema.” He has found a good location for it: The interior space is accented with moldering ceiling tiles, burlap walls, painted concrete, and frayed carpet runners. A crewmember, Jon Meyers, cranks up a fog machine. McCarthy and the rest of the crew — Jesse Davis, Kent Hamson, Kasey Dees, and Nathan Duff — are preparing a scene built around a casket near the screen at the bottom of the theater well. Inside the casket, the corpse — actor Anthony Gray — is wearing a hat. Looking on from above him are the scene’s mourners, actors Zach Paulsen, Kenneth Farmer, and Brandon Sams.

From 9 a.m. until midnight on a Saturday, the cast and crew have to capture everything they need for Midnight Movie, a lengthy trailer for a script McCarthy has written. Ideally, someone will see the finished trailer and help finance the making of the actual feature.

Dan Ball

Dan Ball

Mike McCarthy

But all that is later. Right now, the production has to shoot about 15 scenes at four locations in one day. On the shoot, McCarthy is lively, funny, confident, and efficient. He improvises, but everything is well set up and prepared for, and he trusts the opinions of his crew. He knows what’s in his mind and knows what he sees; he only needs to know what’s in the camera lens.

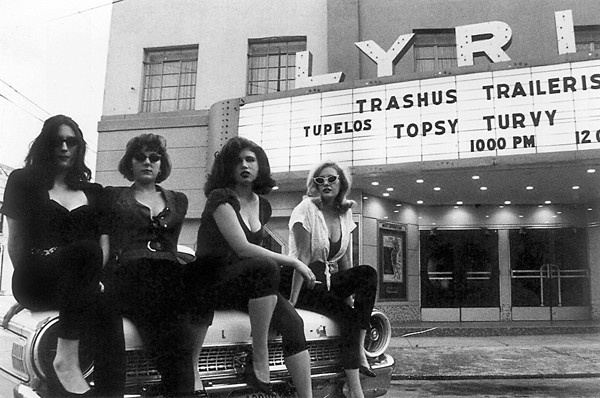

“Guys, crank up the grieving,” he directs the actors. Paulsen plays Brandy/Randy, whom the script describes as “a small-town cross-dresser with big dreams … a ‘Frankenfurter’ inside a Tennessee Williams bun.” Paulsen is wearing the same coat that D’Lana Tunnell wore in McCarthy’s seminal 1995 film, Teenage Tupelo. Farmer plays Charlie, an homage to Jimmy Cliff in The Harder They Come. Sams is Eraserhead, with an appropriate hairstyle. A scene filming later in the night will feature Alex and Henry Greene as Jodorowsky’s El Topo and son.

“Make it be like the Cecil B. DeMille of this kind of thing,” McCarthy says. After a clock check, McCarthy puts his producer hat on and says, “We’re doing all right on time, but barely. Which is the way it always is.”

After the scene, the crew helps Gray (who plays murdered theater owner Ray Black) out of the personal-sized tomb. It’s an expensive-looking prop. McCarthy names a funeral home in Memphis he has worked with before. He’s a filmmaker who needs coffins sometimes.

Cult of personality

Robin Tucker

Robin Tucker

Mike McCarthy (center) directs a scene from Cigarette Girl with cinematographer Wheat Buckley (left) and star Cori Dials (right)

May 2014, Memphis — It looks as if Mike McCarthy’s brain has exploded all over the walls and ceiling of the attic of his Cooper-Young home, as if his mortal cranium can’t contain all of the immortal pop culture that resides within it. Every flat space of wall and ceiling angles features the images of Elvis Presley, David Bowie, Bettie Page, Frankenstein’s monster, Brigitte Bardot, Godzilla — and a score more — and is stuffed with the artistic output of Robert E. Howard, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Michael Moorcock, Camille Paglia, David F. Friedman, Marvel Comics, Famous Monsters, the Replacements, and, crucially, items related to McCarthy’s own work. Here, in the inner sanctum, he keeps scripts, props, art, comic books, a drum set, and the first magazine he was published in, and on and on.

“My psychosexual stuff is over there in that corner,” he says, pointing in the attic, though he could just as well be talking about a patch of real estate in his mind.

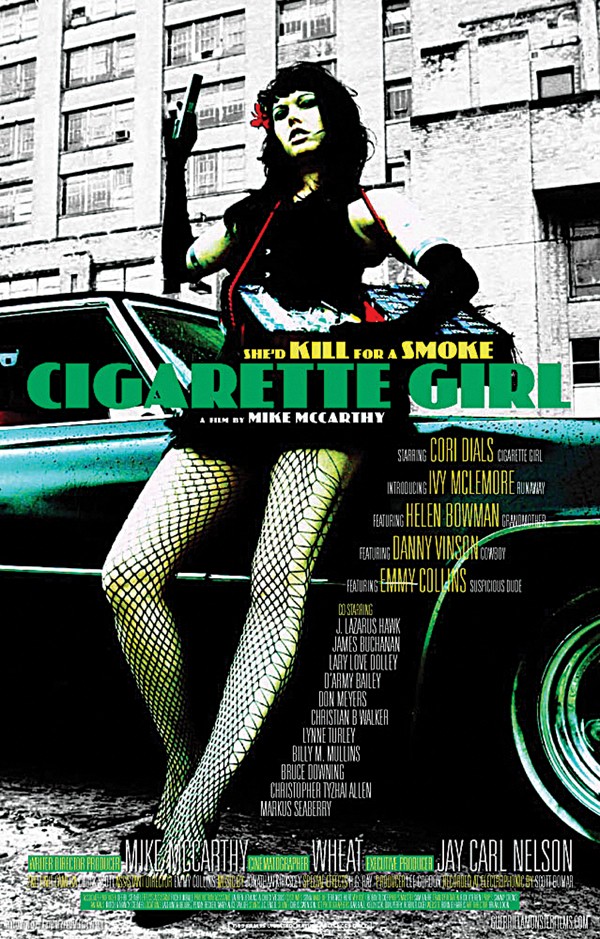

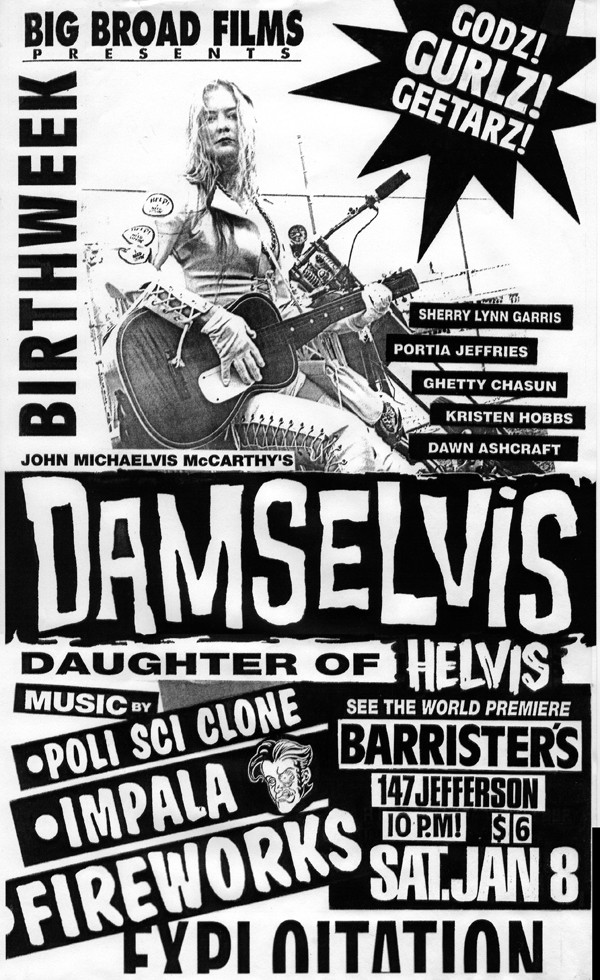

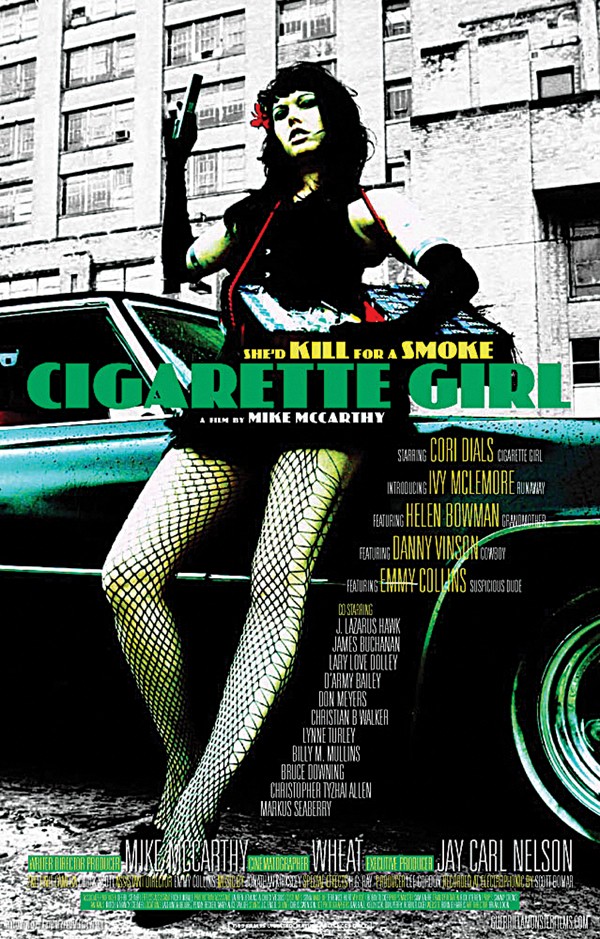

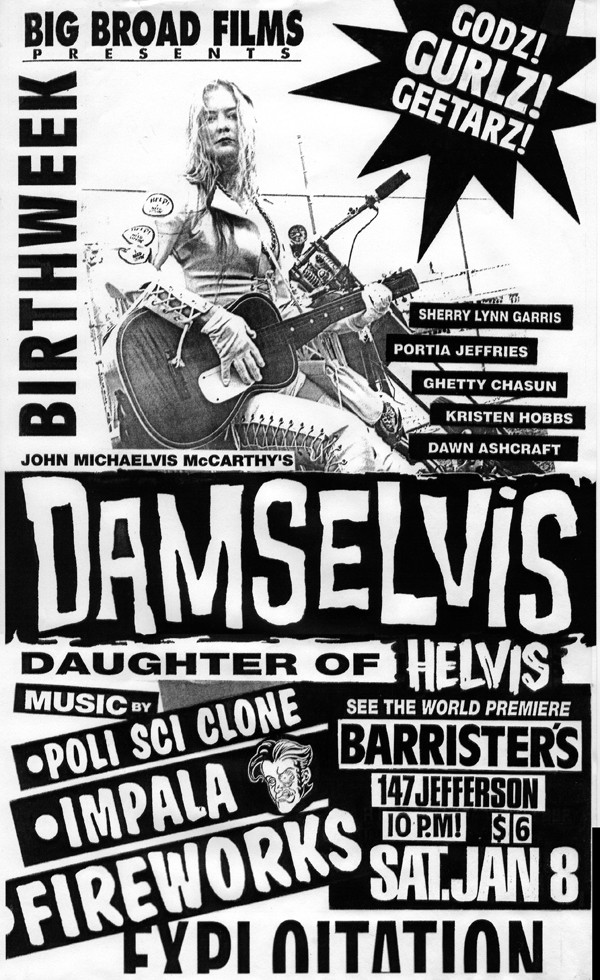

McCarthy has consumed, internalized, and analyzed American pop culture in the 20th century. What he has produced in turn is a filmography — including the features Damselvis, Daughter of Helvis (1994), Teenage Tupelo (1995), The Sore Losers (1997), Superstarlet A.D. (2000), and Cigarette Girl (2009) and the short films Elvis Meets the Beatles (2000) and Goddamn Godard (2012) — that interprets that pop cultural cosmos into a visionary underground art. Many filmmakers, Memphis obsessives from around the world, and other non-mainstream consumers revere him.

Among those influenced by him are the filmmakers Craig Brewer and Chris McCoy.

“I feel like I took a college course from Mike McCarthy,” Brewer says. “Since the time I started making films in Memphis, he has always served as my hero in everything in life. He’s passionate about making movies, and he is passionate about the region he lives in, and the history, and how to honor and preserve that history. I ran from home and the ideas that came from [my] surroundings, where Mike was embracing it and perhaps even exorcising demons through his work.”

Brewer helped edit Superstarlet A.D. so that he could learn how to edit his own film, The Poor & Hungry, and Brewer produced, shot, and edited Elvis Meets the Beatles, which he calls “one of the best experiences of my life.”

McCoy says, “In the early ’90s, I was involved with a group who were inspired by Robert Rodriguez and Steven Soderbergh to make an independent film. I co-wrote the script and we had about $20,000 pledged to the project. But this was before the days of digital, and just the film cost alone would have eaten up the entire budget, so we abandoned the project as undoable. And then, Mike McCarthy came along and proved that it could be done.”

Memphian Rick O’Brien has assisted McCarthy over the years with technical and production support. O’Brien says, “Step into the world of Mike McCarthy and you’ll experience a wild mash-up of 50 years of fringe-pop culture. Mike could be the bastard love child of Russ Meyer, John Waters, and Tempest Storm. Or maybe Elvis … only his mother knows.”

May is McCarthy month in Memphis (alliteration not intended.) Cigarette Girl is being released by Music+Arts, and McCarthy is screening many of his films at the May edition of the monthly Time Warp Drive-In at Malco’s Summer Avenue venue. His films are steeped in the traditions of exploitation cinema, including nudity and violence and rock-and-roll.

David Thompson

David Thompson

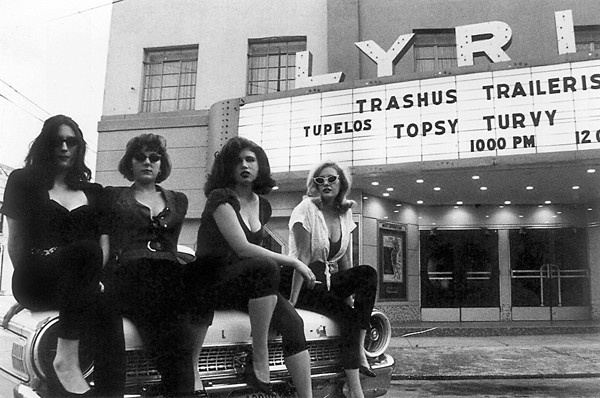

On the set of “Teenage Tupelo”

Watching them, you might think, where in the world did all this come from?

The man who fell to Memphis

1963-1993, Mississippi & Memphis — “Unless you can fixate on something, you don’t learn the true value of it,” McCarthy says. His own biography is something McCarthy is fixated on. Certain geniuses, such as James Ellroy or Alison Bechdel, possess a profound intellectual introspection. McCarthy fits in this category comfortably.

He was born in 1963. The way McCarthy’s mind sees things, there’s a numerology that glows in the structure of the universe. It’s personal and universal, and it can be observed if you sit still long enough. “I was born six months before JFK was assassinated, which was nine months before the Beatles got here,” McCarthy says. “So, 1963 was the last pure year of American pop culture and its influence around the world. The following year, the Beatles would arrive, and the European influence would follow, ironically based on Memphis music. I was conceived in the Lee County Drive-In in Tupelo, and I lived 14 years in the golden age of pop culture, before Elvis died.”

Much of McCarthy’s biography has been recounted in stories over the years, but, since the telling of it has evolved, it doesn’t hurt to set the record straight about exactly what happened and when. He was raised by John and Mildred McCarthy outside of Tupelo. His mother had been a Georgia Tann baby, one of the children who came out of the woman’s infamous Memphis black market adoption agency. His parents attended the famous 1956 Mississippi-Alabama Fair and Dairy Show, where Elvis performed. They can be seen at the top of the bleachers in Roger Marshutz’s famous photo of the concert.

McCarthy grew up at the end of a gravel road, raised on comic books, monster magazines, and other pop that managed to trickle down to him. “On a good night we might pick up Sivad,” he says, referring to Memphis’ monster movie TV host. McCarthy consumed the culture he “could pick up in an analog way, or what was in the grocery store in a spinner rack. Music, I knew nothing about, because corporations had already settled in on it. I didn’t know at the time that rockabilly had been created in my backyard.”

When he was 20, McCarthy learned on his own a staggering truth the consequences of which continue to reverberate: He was adopted. “There’s a certain amount of tragedy, but it’s kind of a cool tragedy, because I decided I would mythologize my gravel road. Instead of street cred, I’ve got gravel road cred.”

Charle Berlin

Charle Berlin

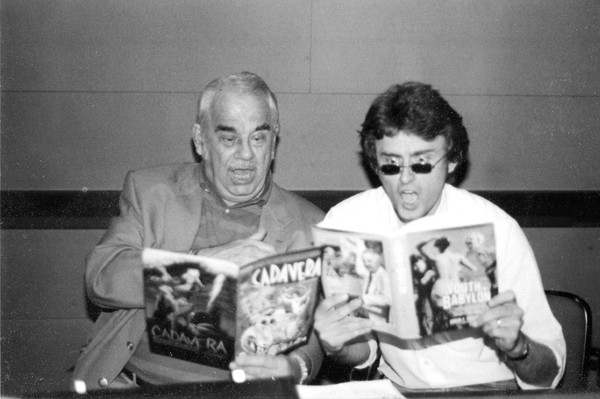

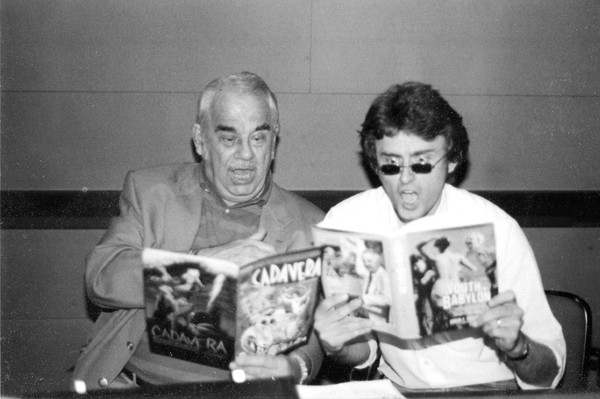

McCarthy meets cult filmmaker David F. Friedman

More bombshells: He was the second of four children his biological mother had. To this day, McCarthy doesn’t know who his biological father is. (His brothers do know who their dads are: “Another angst-ridden detail,” he says, laughing.) He did learn, however, that his biological mother also attended the Fair and Dairy Show, and, moreover, she also could be seen in the Marshutz photo — just a few feet away from the King’s outstretched hand.

When he was 21, McCarthy moved to Memphis. “The point where I should have looked into my past, I moved to Memphis and turned it into art,” he says. “It took me 10 years to focus my anger into an Elvis-oriented art plan.”

Eric Page

Eric Page

Distemper

He came to grad school at Memphis College of Art but dropped out and spent a few years playing in punk bands like Distemper and Rockroaches. He lived with his parents again to work on comic books, including material that would be produced by the renowned alternative publisher Fantagraphics.

He discovered the cult film subgenre. It changed everything. “I realized cult cinema was achievable on my own,” he says.

If those are the facts, the why of it all is left to McCarthy’s interpretation, both artistic and anecdotal, and is the basis for the mythology he has created in the film Teenage Tupelo and developed further over the years. He imagined that Elvis was his biological father: “All these things led to my breaking away from Mississippi, so that I could look back and mythologize with whatever details slowly came down to me from my adopted parents or my newfound brother at the time. So I reimagined the conversation my grandmother had with my mother when she was about to give birth to me. ‘You’ve already had one kid with this guy who left you, you’re certainly not going to keep this second kid.’ So I made my grandmother into a villain — who Wanda Wilson plays in Teenage Tupelo.”

Ground Zero

20th century, America — “Elvis is 21 at the Tupelo Fair and Dairy Show in 1956, halfway through the arc of his life,” McCarthy says. “That day he sings to both my mothers — and thousands of field hands and factory workers. He reaches the ascent of everything he will be. He conquers pop culture by 21, and then he just enjoys the downward slope. Sure, there are moments of greatness, but his life as art belongs on that day between Tupelo and his home on Audubon Drive in Memphis. So what does Tupelo do? They tear down the old Fairgrounds.”

Ground zero for American pop culture is the purity and naiveté of rock-and-roll at its inception, when the middle class consumed and supported uncorrupted artists. The era ended when rock-and-roll, a singularly racially integrated art form, became commodified by commercial interests and became the product called “rock.” American pop culture died to an extent when Elvis did. Punk was the last pure expression of rock-and-roll.

However, that isn’t to say that rock-and-roll is dead and buried, McCarthy argues, because the pure creations from decades ago are still relevant. Worshipping at the feet of this cultural deity is still a worthwhile endeavor — and don’t confuse it with nostalgia and sentimentality, he says, which “don’t apply to things that are still relevant.”

He sees the relevance of rock-and-roll, still lingering in the arifices of the past, and he fights to protect it. “Memphis should be a time capsule for that world, where blues music and country music combined to become rock-and-roll,” McCarthy says. “We don’t need to recreate it: It already happened. We can base an entire world on that model, if we would just stop tearing that world down.”

Creating a Monster

1994-2014, Memphis — As scarring as his biological drama was, McCarthy received considerable support and love from his adopted parents. One important attribute McCarthy would learn from his Greatest Generation parents was “a Depression-era ethic, so that I could deal with poverty when I came face to face with it later, when I decided to be an artist.” He would call upon that lesson time and again. His films were low budget; he didn’t make money off of them; and he struggled to make ends meet. Much of that was by design as part of an artistic austerity. “Being a filmmaker in America is the most narcissistic, self-centered thing you could be. It even approaches evil,” he says with a laugh.

“I always wondered why the circus is a metaphor for craziness,” McCarthy says. “If that were really true about the circus being ‘crazy,’ we would never take the kids because it would be too insane. In reality, the circus contains a big ol’ safety net. So the craziness is simulated, sort of like a film festival or video game. What happens when you remove the safety net? That’s the real circus. When you have no safety net, no guaranteed salary, no trust fund, no nonprofit — that’s the last 20 years of Guerrilla Monster.” Guerrilla Monster’s three rules were: Don’t ask permission; shoot until they make you stop; and deny everything.

Don’t call McCarthy’s films “indie.” He’s careful to draw a distinction between indie film and underground film: “The indie scene is basically mainstream filmmaking without money,” he says.

“I’ve been compared to Truffaut, Fellini, and Orson Welles, all by asking women to take their clothes off in the middle of the night in Mississippi with a camera.”

It’s now or never

Past, present, and future — Much of what occupies McCarthy’s brain is what is now gone. “I miss Memphis Comics. I miss Pat’s Pizza. I miss Ellis Auditorium. I already miss the Mid-South Coliseum. I identify with it. I miss me.”

McCarthy takes the time to note that he and the Coliseum were born in the same year, and suggests we drive over to appraise its current state of neglect. McCarthy was a founding member of Save Libertyland, active in preserving the WHBQ booth at the Chisca, worked at Sun Studio for a time, served as a tour guide in Memphis, and is a strong advocate for preservation. “These things will be important to smart people 100 years from now,” he says. “And they’ll blame us as a generation that created a serious criminal offense against the 20th century, the American century, by tearing down the rock-and-roll structures that were in place in Memphis at the time when all of this music was created, when all of this goodwill was created.”

Preservation probably isn’t exactly the right English word for it. McCarthy’s advocacy isn’t about stasis but about vitality. “The further you get away from the pulse of something, the closer you get to the death of it,” he says. “This bleeds into my dislike of historic markers, because we keep those people in business.” For a few years, he has been developing a documentary about it, Destroy Memphis (tagline: “See it while you can”).

“I wasn’t born in the ’50s, where I could take advantage of the thriving middle class that spit out rock-and-roll, great movies, and great comic books — so great they were outlawed by the government. I worship those things. Those things are greater than any dogmatic religious principles.”

His thoughts on the subject are similar to those about Guerrilla Monster, which, he announces, may have reached its end. The fact is, he can’t afford to keep his cinematic pursuit going without financial backing. He has a family to support. “Underground films are fascinating to watch because you see struggle. I’ve been through 20 years of good old-fashioned punk rock struggle. Deliver me from struggle.

“In the ’90s,” he continues, “I used to say the voice of a dead twin told me what to do. Now I’m not sure. Sometimes I feel like I’ve lost my way. I feel like I’m in the prime of my filmmaking life, but I can no longer make films ‘on the cheap’ where I keep asking people to do things for me for free. Guerrilla Monster has served its purpose. ‘Twas reality that killed the beast.”

If he has to, he will focus on comic books, which carry much less budgetary overhead. “I probably have another 20 years before my hand starts to shake. You’ve only got so much time to create.”

What he really wants to do, though, is to get his films financed. He has a script, Kid Anarchy, based on a comic book he created in the 1980s with his friend George Cole. McCarthy, Cole, and Memphis filmmaker G.B. Shannon have written the script. It’s much more accessible than his past films. He thinks it could be his shot.

“I always thought Mike would be fantastic working with a solid producer and a solid script,” Brewer says. “He’s very professional and he’s really prepared.”

“If I got a million bucks to make Kid Anarchy, it wouldn’t be a Guerrilla Monster movie, it would be an indie movie with punk rock principles, closer to Richard Linklater or Mary Harron,” McCarthy says. “It’s about a 15-year-old boy in 1984 who gets kicked out of Memphis for being a juvenile delinquent. So, he goes to live with his religious aunt and uncle in northeast Mississippi, like a true fish out of water. He has to attend a new school, to pray before dinner, and he can’t listen to the Dead Kennedys anymore. It’s akin to Breaking Away, or every S.E. Hinton novel; it’s a ‘let’s discover the next Matt Dillon’ movie. It’s all that. But I can’t make it for nothing.”

In other words, it’s the McCarthy story told in reverse. Is the happy ending at the beginning or at the end of the story?

Producer John Crye, former creative director for Newmarket Films (where he oversaw the acquisition, development, and distribution of Memento, The Prestige, Whale Rider, Monster, Donnie Darko, and The Passion of the Christ), is helping McCarthy package the film in terms of investment and talent. “In this economy, the safest investments in film are with those filmmakers who can produce a $1 million film that looks like a $10 million film,” Crye says. “McCarthy proved with Cigarette Girl that he can make tens of thousands of dollars look like hundreds of thousands. The time is right for him to come out of the underground, work with a better budget, and start creating more commercially viable movies. Kid Anarchy is that. It is to Cigarette Girl what Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused was to Slacker.”

“The blues wouldn’t have been created without oppression,” McCarthy says. “Jesus wouldn’t be worshipped without crucifixion. But without any of that you don’t get resurrection. I want resurrection, I want to make money.

“I want to make Kid Anarchy. So crucify me.”

The Mike McCarthy/Guerrilla

Monster Films calendar of events:

* May 16: Mike McCarthy on WKNO’s “Checking on the Arts” with Kacky Walton

* May 17 : Malco’s Studio on the Square screens Cigarette Girl at 10 p.m.

* May 20: Cigarette Girl out on DVD, archer-records.com/cigarette-girl

* May 23 : Release party at Black Lodge, 9:30 p.m. With appearances by

Cigarette Girl stars Cori Dials and Ivy McLemore and live music from

Hanna Star and Mouserocket

* May 24 : Summer Drive-In screens Guerrilla Monster Films, featuring

Elvis Meets the Beatles, Cigarette Girl, Teenage Tupelo, The Sore Losers,

Superstarlet A.D., and Midnight Movie

For more about Mike McCarthy, including streaming videos of his films, essays, and the script for Kid Anarchy, go to guerrillamonsterfilms.com.

Dan Ball

Dan Ball  Robin Tucker

Robin Tucker

David Thompson

David Thompson  Charle Berlin

Charle Berlin  Eric Page

Eric Page