Drogon is silently judging you.

Game of Thrones was a great show that grew to love the wrong thing. Its early adopters worshipped how it fully realized its alternate universe. Its increasing budget to film battle sequences (off-screen in the manner of a stage play at first) became what its makers thought its true worth. Seduced by the dark side of their production schedule, spectacle became their master, writing their afterthought. Details grew fuzzy, their beautifully constructed dollhouse fell apart, as its audience watched not with desire but light hatred, not in fire but ice.

But even in its death throes, the penultimate episode took time to be true to itself and deflate its heroes. It numbed the viewer with endless shots of medieval civilians running from dragon firebombing by former savior, Daenerys Targaryen. Innocents ran down corridors, caught on fire, and turned to ash. Modeled after U.S. and British massacre of German civilians in Dresden during World War II, it was disgusting. All-powerful ninja Arya and stern-faced warrior Jon Snow ran around helplessly while Daenerys and lieutenant Grey Worm went mad. It may be garbled Cliff Notes for an ending George R.R. Martin may never write, but I’ll hold onto it the way a housecat does a dead mouse: long past the point of usefulness. I loved this show.

[pullquote-1] It is not normal for TV shows to end well, especially sci-fi fantasy. Lost and Battlestar Galactica adopted religious smokescreens for their inability to come up with secular answers to long-posed riddles. Game of Thrones didn’t, completely abandoning the lore of its competing in-universe faiths. Instead, it built to tough-guy nihilism, followed by happy outcomes for the majority of its action heroes and some light Tolkien-style epiloguing. Bran is king, for some reason.

There are many popular theories about why, outside of outpacing their source material, the writing quality of showrunners David Benioff and D.B. Weiss has gone from more thoughtful than most fantasy to exactly as loose and empty as much of it. Cocaine and burnout are solid options, as is a desire to move onto their recently-announced Star Wars trilogy, or the cosmic injustice of a cruel god. I think that, just as they relied on assistant-turned-writer Bryan Cogman for heavy lore lifting in the first seasons, they are relying on a different one now, Dave Hill (who helped elevate the character of Olly), and he’s just not as skilled at helping them craft sturdy plots.

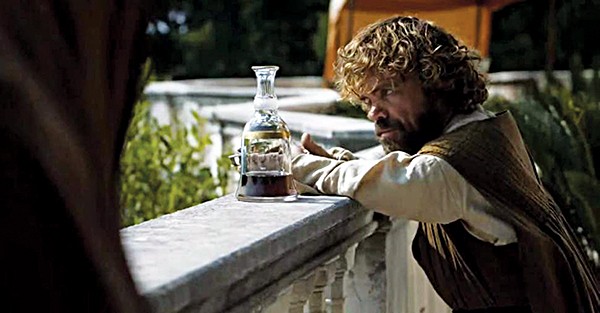

A victorious Daenerys Targaryen addresses her troops in the ruins of King’s Landing.

As many have pointed out, the series dilutes the antiwar message of the novels by its sometimes glorification of the hard-bitten warrior. How cool the Hound looks fighting the Mountain with a dragon flying behind them registered more strongly than his late assertion to mass-murderer Arya that revenge is hollow. (Likewise the online cry of “Cleganebowl!” was initially ironic: people mocked treating a death fight between brothers like an organized sport, until repetition made them sincere). The point shouldn’t be that Daenerys went crazy and killed civilians: it should be that all mass violence leads to noncombatant death, and warriors and states use it far too freely, with increasingly meaningless justification.

Director Miguel Sapochnik and Emilia Clarke did excellent work selling that slaughter. But the lack of characterization in Dany’s turn from a protector of the common people to their mass murderer made the moment nonsensical. Her reasons work when written out: a need to rule by fear, losing advisors and dragons, and numerous surrender bells frustrating or stimulating her bloodlust. Onscreen it creates a disconnect, that does clumsily get the nature of being bombed right. One minute you’re following the propaganda of a government at war, the next you’re being indiscriminately killed. Violence does not resolve character arcs. It just ends you.

Iron Throne? Not so much.

Martin’s ongoing suggestion is that this would happen with any king or queen in the right circumstances. The show’s unfortunate implication is that Dany is worse than her formerly gray, also-murderer co-heroes because she is female, from a foreign land and rides magic lizards. It’s special pleading that the other warriors suddenly care so much about collateral damage.

For the American audience, the use of Dresden as source material is a quiet self-indictment. Your tax dollars prop up one of the most powerful militaries in the world. My favorite show is saying that all war is immoral. If only the comfort and catharsis its audience found in that message could translate into peaceful action by us.

courtesy HBO

courtesy HBO  courtesy HBO

courtesy HBO  courtesy HBO

courtesy HBO