The Farm School in Summertown, Tennessee, is a kid’s dream come true.

Students decide their own class schedule, who will teach what subjects, and where they’ll go on field trips. In addition to traditional subjects such as trigonometry and English, they also take classes on “Personal and Planetary Well-Being” (a hippiefied biology class) and “Radical Civics.” Last year’s history class was titled “History of U.S. Imperialism.”

On a Friday morning, nine youngsters, ages 10 to 17, are gathered in a circle in a modest classroom. Some sit on ragged couches or recliners. Others sit cross-legged on the floor. A few gently rock in computer desk chairs. One kid fiddles with a buck knife.

Their T-shirt-wearing teacher/principal, who calls himself Peter Kind Field, also sits on the floor, hugging his knees to his chest as he reads the students’ short stories aloud.

In the center of the room, a black-and-white rabbit hops aimlessly. Some students reach out to pet the bunny as it passes. When it heads in Field’s direction, a few kids giggle. Field looks down to find the rabbit nibbling on his paperwork.

“Cookie, stop eating my attendance sheet!” says Field, laughing. More giggles from the students.

This is not a traditional school. But then again, the Farm is not a traditional place.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

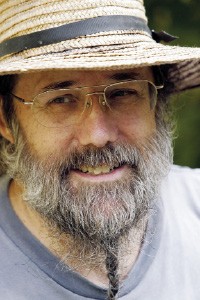

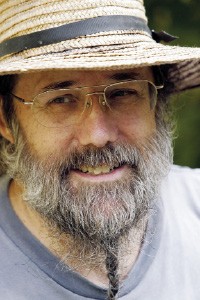

Alan Stuart Graf reaches radical civics at the Farm School.

Founded in 1971, this sprawling commune was a safe haven for West Coast hippies seeking a place to call their own. In the days of tie-dye and free love, 250 free-thinking young vegetarians, mostly from San Francisco, settled in Summertown to form their own society.

They purchased 1,000 acres of lush rolling hills and wooded forest an hour south of Nashville. They started a soy dairy, where they made tofu and soymilk, and a vegetable farm. They built houses from scratch. A horse-drawn cart hauled five-gallon bottles of water from the nearest town. When children were born, the “Farmies” set up a school.

Early settlers turned their life savings and all their possessions over to the Farm, and resources were shared equally. In its heyday, the Farm’s population exceeded 1,500. It was an experiment in communal living, and somehow it worked. For a while anyway.

Today, the Farm is run democratically, and its population has dwindled to about 300. It’s one of a handful of surviving hippie communities, and most of its original members are nearing retirement age. Fortunately, for the Farm’s future, some of their children have stuck around and are now having kids of their own.

“We’re trying to get more young people, so we have a constant turnover. We want enough children being born and raised here that we have an even distribution of ages,” says Albert Bates, who’s lived on the Farm since 1972. His children and grandchildren still live there.

In an age where global warming is a growing concern and oil prices continue to rise, the older Farm members believe their style of earth-conscious, community living is more relevant than ever. But whether the third generation will stick around to keep the community alive is anyone’s guess.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Teens direct their own learning

Hippie Haven

The road to the Farm doesn’t look much different from any rural Tennessee route — green fields, woods, an occasional grazing horse. But visitors know they’re in the right place when rusty grain silos adorned with flaking paintings of colorful mushrooms come into view. Deeper into the Farm, small homes with outdoor murals of trees and sunbeams dot the landscape.

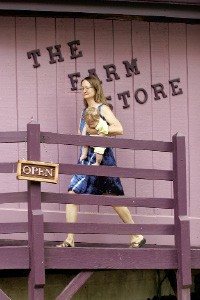

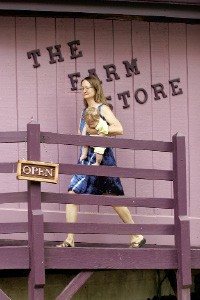

Just off the main road at the Farm’s modest health-food shop (appropriately named the Farm Store), residents pick up ready-to-eat meals such as Thai peanut tofu sandwiches (most of the Farm’s members are still vegetarians) or grocery items.

Aside from the abundance of healthy food choices and multihued murals, the scene looks like that of any other small country town. But it’s evolved quite a bit from what it was.

“In the late 1960s, the young people were gathering in San Francisco, and they eventually watched the hippie movement disintegrate out there due to all the human frailties. There were just too many people and nothing for them to do,” says Douglas Stevenson, an original Farm member who now runs the community’s website design and video production company, Village Media.

Stephen Gaskin was an English professor at San Francisco State University at the time. He began holding weekly spirituality classes each Monday night to give young people a positive place to gather. As class topics centered more and more on the importance of community, close bonds were formed.

When a group of clergymen held a conference in San Francisco on how to deal with the hippie movement, they invited Gaskin to speak. They were so impressed, they asked him to go on a nationwide speaking tour.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

A rabbit attends class at the Farm School.

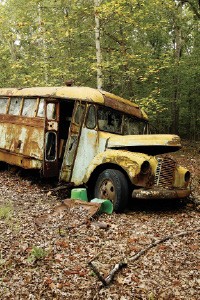

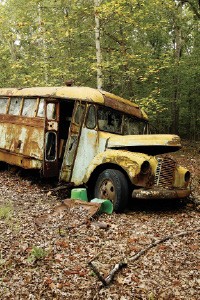

Not one to abandon his students, Gaskin invited them all along. The students gathered money and purchased old school buses in order to tour the country.

“By the time we got to the end of the tour, we had 50 school buses full of people and I’d spoken in 42 states,” says the 72-year-old Gaskin, who still resides on the Farm with his wife Ina May.

“But we metamorphosized on the caravan. Before, we’d been a bunch of people failing out of college or living with our mothers,” Gaskin says. “When we got back to San Francisco, we didn’t want to go back to doing that kind of stuff. We’d become something new while on the road.”

The group began to look for a place to form a commune. They’d had a pleasant experience when traveling through Tennessee, so they began looking for land near Nashville.

When the FBI got word that a group of hippies was looking to settle down in Middle Tennessee, area realty companies were advised not to sell to them. But the group eventually found a sympathetic landowner who offered to sell his thousand acres in Summertown.

“We were a bunch of hippies. We didn’t have any credit, but the landowner, Carlos Smith, carried the note himself. We ended up paying him back better than he expected,” Gaskin says. “And we outfoxed the FBI.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Mushroom murals on a grain silo, a reminder of the Farm’s origins origins in 1971.

Life was hard in the early days, as the former city-dwellers learned to live off the land. As Gaskin fondly remembers, “All we had for plumbing was a bucket. We were very collective in the beginning, but when you’re poor and there’s a lot of you, that’s the only sane way to be organized.”

“Everything came about by need,” says original member Thomas Hupp, who now works at the Farm’s book-publishing company, which prints hundreds of popular vegetarian cookbooks. “We developed a farm crew to grow the crops and a baby crew to deliver the babies. Eventually, we bought an old printing press and said, let’s make books on who we are and what we do.”

Everything at the Farm was given a simple title. The book company was called Book Publishing Company. The soy dairy was called Soy Dairy. The main road was named Farm Road.

“We were careful in the beginning about what we called ourselves,” Hupp says. “We called everything what it was to keep from becoming a slave to symbols.”

The place operated as a collective. Each person was provided food and plenty of land to build on. Some of the women who’d learned to deliver babies while riding on the caravan set up a midwife center. Soon, pregnant women from across the nation were traveling to the Farm to give birth.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

A Caravan bus, a reminder of the Farm’s origins in 1971.

The group even formed a nonprofit organization called Plenty International to help people in other countries affected by natural disasters. More than 100 volunteers traveled to Guatemala after the 1976 earthquake and helped build a soy dairy.

As word spread about the Farm, hippies from around the country began arriving by the busload. Some came to visit and never left. Barbara and Neal Bloomfield came to deliver their baby through the Farm’s midwife program.

“We made good friends, and we decided we wanted to raise our children in a community,” says Barbara Bloomfield, a vegan cookbook author who raised her three kids on the Farm.

The Farm’s population rose to 1,500 by 1983, but with more and more people drawing from slim resources, the communal system began to fall apart.

“We’d gotten to a place where we weren’t even keeping good books because we were so big,” Gaskin says. “So we decided to break the collectivity and start having people pay dues.”

The Big Change

Not everyone was pleased with the new set-up, dubbed the “changeover” by folks still living on the Farm. Many who’d migrated to Tennessee for the communal experience weren’t prepared to earn their own salaries or own their own homes. Others were disenchanted when they realized the experiment wasn’t working. People left in droves. “It was a great dissolution. Some people were, like, the dream is over. We’ve failed,” Stevenson says.

For some, life got easier after the changeover. Neal Bloomfield earned a good living operating a construction company. The new system allowed him to keep his profits rather than turn them over to the collective.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Barbara Bloomfield prepares boxes for the Farm’s book publishing business.

“We didn’t mind keeping our own money,” Barbara says. “The old Farm was definitely fun, but it got intense.”

Attorney Alan Stuart Graf, who’d been living on the Farm since 1972, wasn’t as pleased with the new system and left.

“One of the biggest problems we had back on the old Farm was who was going to do the dishes,” laughs the ponytailed lawyer. “I left in 1984, when I realized the Farm wasn’t doing what it set out to do in the first place.”

The population scaled back to its original size and remains fairly stable today. But unlike many others who left, Graf returned in 2006 after spending years working as a civil rights attorney in Portland, Oregon. Today, Graf works as a Social Security and disability lawyer, teaches radical civics at the Farm School, and serves on the Farm’s board of directors.

He’s grown more comfortable with the way the Farm operates today.

“If someone doesn’t like something now, they can get a petition together with 15 percent of the voting members,” Graf says. “We still try to base our system on the highest principles of humanity: love and compassion.”

Today, a seven-member board of directors operates the Farm. It takes responsibility for the Farm’s financial assets, oversees health and safety, decides where roads are built, and deals with construction issues on communally owned buildings. (The land, the Farm store, and tofu dairy are still collectively owned.)

“Every year, people put in proposals on what should be in the Farm’s budget,” says Barbara Bloomfield, who serves as chair of the board.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Ina May Gaskin teaches a class in midwifery at the Farm, located south of Nashville.

Members pay $75 a month in dues. The money goes toward basics like water and roads. Members can pledge to add more money to the budget for extras such as maintaining the swimming hole or the community cemetery.

New members are always welcome, but the Farm’s membership committee must first evaluate the finances of potential members to ensure they’re economically viable.

“We’ve evolved quite a bit. We were only communal for 10 years, but we’ve been living like this for over 20 years,” says Stevenson, who stuck around through the change. “We’ve had time to finish our houses and people have gotten careers. They’re gaining real incomes.”

One thing that may strike visitors as strange is the lack of farming on the Farm. After the governing system changed, so did the need for residents to grow their own food.

“We don’t farm as much now. It’s economics and scale,” Gaskin explains. “We can buy organic soybeans cheaper than we can grow them because we’re not a big grower anymore.”

But other Farm businesses continue to thrive. Barbara Elliott runs the soy dairy in a building next to the Farm Store. Every couple of weeks, her small crew produces 3,500 pounds of tofu, as well as soy milk and soy yogurt.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

“We started this in the 1970s to include a variety of protein in our diets,” Elliott says. “Eating soy and plant protein also helps the environment.”

Some of the tofu is sold in the Farm Store, but they also ship the bean curd to health food stores in Nashville. The soy milk and yogurt are sold locally.

Business is also booming at the Book Publishing Company, where about 250 titles of vegetarian cookbooks, nutrition guides, and books on midwifery and Native American spirituality are currently in print. Since 1972, the company has published around 400 titles.

“Our company has actually doubled in the past couple years,” Hupp says. “It began as a creative way to generate income for the Farm. It was the one place where we got to use our college degrees.”

After the changeover, the Farm School began charging tuition to pay teachers’ salaries. As a result, many Farm parents began busing their kids to area public schools. Today, the Farm School’s 20 or so students are a combination of Farm children and kids from the surrounding communities.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

“Traditional schools do things backward,” says Field, who moved to the Farm to teach after working in New York’s public school system. “We’re interested in empowering children and allowing them to learn about what they’re really interested in.”

The Farm also has a small medical clinic set up for basic care and boasts an extensive midwife-training program. After learning to deliver babies by accident on the caravan, Gaskin’s wife Ina May wrote Spiritual Midwifery, now considered the definitive guide on home birthing techniques.

“We didn’t plan on being midwives. I was an art major and Ina May had a masters in English. But by the time we got here [in 1971], we’d delivered nine babies on the caravan,” says Pamela Hunt, who teaches midwife training courses. “Now about 120 people come here every year for workshops.”

Going Green

At the Ecovillage Training Center, the Farm’s training site for green technology and construction, various clay buildings sit unfinished. The largest one, boasting a carved green dragon spanning the length of the building, sits near the far end of the one-acre site.

Inside the cave-like Green Dragon, an experimental structure built from adobe clay, cord wood, and straw bale, things are very much still under construction. The eyes, nose, and mouth of a half-carved Aztec warrior figure protrudes from one wall. His mouth is constructed to be used as a fireplace. Another wall features jutting rocks that will one day serve as a climbing wall. Outside, a tarp covers the unfinished roof.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Albert Bates of the Farm’s Ecovillage Training Center

Albert Bates, director of the Ecovillage Training Center, says the building will one day serve as a recreational facility for the center’s apprentices and interns. The construction of the facility has been a project for Ecovillage interns using green building techniques.

The Ecovillage Training Center was developed in 1995, when Farm residents saw an emerging need for alternative, sustainable building practices. Today, people travel here to get hands-on training.

While studying at the Ecovillage, students stay in a solar-powered inn. It can accommodate up to 30 people without drawing from the conventional power grid.

Rainwater is collected for the interns’ showers, and the graywater run-off sustains the site’s organic garden. Steam from the Ecovillage’s adobe sauna heats the straw-bale greenhouse.

Though many of the Farm’s homes and businesses purchase electricity from the local power company, the Ecovillage remains as a model for how to live and build off the grid.

“We began as hippies leaving San Francisco to find spirituality. That was way before the term ‘ecovillage’ was even coined,” Bates says.

But Bates, who has authored a book on global warming and one on surviving the peak-oil crisis, hopes his center can influence not only Farm residents but others concerned about their carbon footprint.

“I think the U.S. is going to be going through major economic turmoil pretty soon. The subprime meltdown is one example,” says Bates. “These kinds of things will allow us to expand our horizons and what we mean by a sustainable economy.”

If and when the U.S. does find itself in that scenario, the Farm will be prepared thanks to the technology at the Ecovillage. Gaskin says they’re also prepared to farm again, if necessary.

“We know if times get hard, we’ve got 500 acres that we’ve been grazing horses on for years,” Gaskin says. “We can get right back into farming our own food.”

Of course, the ultimate fate of the Farm hinges on whether or not the younger generation stays. Bates estimates that only one-third of the Farm population is under 30.

“We’re trying to create a space where our kids feel welcome,” Stevenson says. “We want them to settle down here, because in addition to green building, sustainability is about how to pass on ideals from one generation to the next. When we’re dead and gone, we’d like for them to stay here and carry on.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

University of Memphis

University of Memphis  Green Living

Green Living

Maya Smith

Maya Smith  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks