The phrase “fiscal cliff” had not yet become part of the national vocabulary, so at a retreat for the Memphis City Council and city administration one year ago, development czar Robert Lipscomb used a picture of the Titanic sinking in a field of icebergs as a metaphor for the city’s financial ship.

Because of its declining tax base, Lipscomb said, “Memphis has no margin for error. I would suggest that you have a business model which is not sustainable.”

A year later, the ship hasn’t sunk, not yet anyway. Whether Lipscomb’s alternate business model is sustainable remains to be seen. This much is certain. He is at the helm, charting the course for Memphis on four big projects that overlap the administrations of Mayor A C Wharton and his predecessor, Willie Herenton, and, in all likelihood, their successors.

This will be the defining year for the Fairgrounds redevelopment, Beale Street Entertainment District, Bass Pro Pyramid, and Heritage Trail, the name of the proposed redevelopment of two housing projects south of FedExForum. At stake are hundreds of millions of dollars in local, state, and federal funds pledged to the projects for years to come.

This year’s metaphor might be rescue ships. Memphis needs private-sector partners — a developer who can bring a name-brand retailer and hotel to the Fairgrounds, a manager for Beale Street to replace John Elkington and Performa Real Estate, a “game changer” of a grand opening from Bass Pro founder Johnny Morris, and downtown developers who share Lipscomb’s controversial vision for Heritage Trail. After years of delays, false starts, and lawsuits, all of those things are supposed to happen in 2013.

There are some new officers aboard — Janet Hooks replacing Cindy Buchanan at the newly named Division of Parks and Neighborhoods and Brian Collins replacing Roland McElrath as director of Finance — while some members of the vaunted creative class — brand manager-turned-spokeswoman Mary Cashiola and innovation specialist Kerry Hayes — departed to go into public relations. Buchanan and McElrath were holdovers from the Herenton administration responsible for, among other things, Liberty Bowl Stadium and the budget. With them gone, Lipscomb has no peers.

Lipscomb is arguably the most powerful individual in city government since the days of E.H. “Boss” Crump 60 years ago. He deserves as much credit as anyone for changing the face of public housing in Memphis, a transformational achievement. No one has held so many jobs at one time. He is currently director of Housing and Community Development (HCD) and director of the Memphis Housing Authority (MHA) and formerly was finance director. His team has three other key players: former city councilman Tom Marshall and O.T. Marshall Architects, working on Tiger Lane, Liberty Bowl Stadium, and the Pyramid; RKG Associates, a planning and market study firm based in New Hampshire that has done the master plans for the Fairgrounds, Pyramid, and Heritage Trail; and the federal government, whose support is essential for funding the projects.

Lipscomb, wearing his trademark vest sans jacket, typically makes the pitch, while Marshall and RKG provide the numbers, projections, glossy handouts, colorful renderings, and professional know-how. Tom Jones, author of the “Smart City” blog and a former special mayoral assistant in Shelby County government, often is the wordsmith.

As modern-day oracle, Lipscomb’s special gifts include financing tools such as the Tourism Development Zone (TDZ) and Tax Increment Financing districts (TIFs). The gods he intercedes with are mighty but temperamental federal agencies that can dispense wrath (lawsuits) or bounty (grants). Their ways are not known to ordinary mortals. To anger them is to risk ruin.

There are skeptics, however, on the city council and in Shelby County government. TIFs and TDZs basically call “dibs” on taxes collected downtown and in Midtown and dedicate them to specific projects. That leaves less money for elected officials to spend on schools and other needs.

Wharton is scheduled to give his State of the City speech on January 25th. Here is a look at what’s ahead in 2013:

BASS PRO PYRAMID

The world’s biggest man-cave is supposed to open in time for 2013 Christmas shopping. But don’t bet the boat on it just yet. There are some major decisions still to be made.

The lodging component has been described at various times as “a hotel” or “cabins,” which are hardly the same thing.

The future of the two-level observation deck, which has never been open to the public and is accessible only by an interior staircase, is unclear. Lipscomb told The Commercial Appeal in December that “it’s going to blow people away.” But a day earlier, Alan Barner of O.T. Marshall Architects, in a briefing for downtown stakeholders, said the interior design is “fluid” and the fate of the observation deck is uncertain. If the deck is not used, then removing the floor/ceiling would open the rest of the building to natural light through the glass apex.

Calling the shots is Bass Pro founder Johnny Morris. At stake is some $200 million in public funding for redevelopment of the Pyramid and neighboring properties. The Lone Star Cement towers south of the Pyramid have already been acquired and demolished to make way for a main entrance. The floodwall on the west side has been strengthened.

Assuming that Bass Pro opens this year, the next question is what it will do for the Pinch District and the Memphis Cook Convention Center. There is no retail developer yet for the mostly blighted space between the Pyramid and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. The convention center is the “qualified public use facility” that, under a 1998 state law, is the key to the TDZ. The plan is that sales tax increases from tourists shopping at Bass Pro will pay for a bigger and better convention center in Phase 2. The result, according to a project handout: “a game changer.”

KEY DATE: A grand opening no later than November.

BEALE STREET ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICT

As the saying goes, be careful what you wish for. After 30 years, John Elkington is gone, and Beale Street is the city’s problem/opportunity. In October, following a bankruptcy court ruling, he agreed to turn over Beale Street to the city. The mayor was so excited that he promptly announced that “A C Wharton does not want to run Beale Street” and “professionals” will do that.

But who?

There was a time when Belz Enterprises was mentioned as a possible partner, but that day has passed with the failure of the Peabody Place retail center. In 2008, the Cordish Companies, a developer of urban entertainment districts in Baltimore and Louisville, took a look. Beale Street has a stable of experienced, independent-minded club and restaurant operators, including Silky Sullivan, Preston Lamm, and Bud Chittom. B.B. King’s Blues Club is the signature sign on the street, but the legendary bluesman is 87 years old and rarely appears there. To the west, the blighted (but soon to be renovated) Chisca Hotel and MLGW’s headquarters separate the entertainment district from South Main Street. To the east — and just outside the district — is Club Crave, scene of 21 shootings since 1992 and closed in December.

Beale Street may or may not be the state’s biggest tourist attraction, as Kevin Kane of the Convention and Visitors Bureau once said, but it works, either because of or in spite of Elkington’s efforts, depending on your point of view. Say this much: No other city, including some with more financial resources and people, has been able to replicate it. And there is not a McDonald’s or fast-food chain in sight.

Jeff Sanford, former head of the Downtown Commission, was hired as a consultant on Beale Street for the city and is supposed to come out with a report early this year. The big name that gets tossed around every year or so is Justin Timberlake.

“Logic would dictate that the Grizzlies ownership group would be interested in the future of Beale Street, and Justin Timberlake is part of that group,” Sanford said.

Fresh horses would help, but whoever takes over this job will have their hands full.

KEY DATE: Presentation of Sanford’s report this spring or sooner.

HERITAGE TRAIL

Formerly known as Triangle Noir, Heritage Trail was under the radar until last December, when an RKG Associates development and financing plan drew fire from downtown developers, residents, and Mike Ritz and Steve Basar of the Shelby County Commission.

The target area is the partially demolished Cleaborn and Foote Homes public housing projects, southeast of FedExForum and Clayborn Temple AME Church, where Martin Luther King Jr. spoke. Replacing housing projects with mixed-income homes and apartments encouraged big investments at the north end of downtown by St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and ALSAC. The hope is that something similar on a smaller scale could happen on the south end if it is cleaned up.

To pay for this, Lipscomb proposes a TIF that would encompass all of downtown. The 196-page master plan includes the entire downtown core, the Beale Street Entertainment District, and the South Main District and targets some 200 parcels for acquisition by the Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) by purchase or eminent domain. A master developer would be hired by the CRA.

According to a memo accompanying the plan:

“To begin funding implementation, the CRA would establish a downtown TIF District. It is projected that over 20 years the TIF would redirect $102,751,238 of city and county property taxes to the CRA.”

At a meeting in December, CRA board chairman Michael Frick assured a group opposed to the plan that their alarm was premature, and anything the board does must be approved by the city council and county commission.

“A TIF district should stand on its own, creating true incremental revenues. If we desire to subsidize public housing, we should make that direct decision and not fund it indirectly by creating a TIF district,” Basar wrote in a Flyer commentary.

Empowering the CRA with a huge TIF would create another bureaucracy, say other critics of the plan.

“Two bureaucratic organizations that are both burdened with rules — MHA and CRA — would replace one efficient and nimble agency, the Downtown Commission,” said Henry Turley, developer of Harbor Town, Uptown, and other downtown projects.

KEY DATE: CRA action in February.

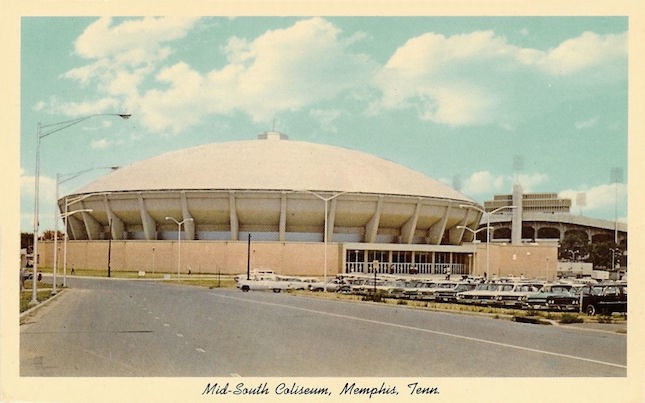

THE FAIRGROUNDS AND LIBERTY BOWL STADIUM

“Not only could they shut the stadium down, they could hold the whole Fairgrounds hostage.”

So said Lipscomb to city council members in December, as they prepared to vote on spending another $12 million on the Liberty Bowl. “They” is the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). At issue is compliance with the Americans With Disabilities Act. Last week, the city council voted 11-2 in favor of an agreement to increase the number of wheelchair-accessible seats and companion seats from the current 266 to 830 in the chronically underused, soon-to-be 59,000-seat stadium.

Lipscomb said the settlement would allow the city to move ahead with plans to present its Fairgrounds vision to the city council on January 22nd and present its TDZ application to the state on February 14th.

The proposed TDZ would include Overton Square and the Cooper-Young restaurant and entertainment district. It would be the second one in Memphis. The “qualified public use facility” required by state law is the stadium. The Convention Center and Tourism Development Financing Act of 1998, amended in 2007, also requires at least $50 million in private investment. In 2008, Turley and Overton Square developer Robert Loeb got preliminary approval for a Fairgrounds youth sportsplex, but the plan was not adopted by the city council and is dead now. Lipscomb said the team’s fee was too high. Turley said the problem was his insistence on an independent board.

In an email to the Flyer, Lipscomb said he was asked by Wharton a year ago to try to bring seven years of legal wrangling to an end.

“Debate is costly in direct costs and opportunity costs over that period and also led to an impasse and obvious rancor between the two sides,” Lipscomb said. “My role was to review it from a fresh perspective and serve as a risk manager and advance a resolution.”

The $12 million extends the useful life of the stadium, he said, and will enhance work already done on Tiger Lane and the Kroc Center, a recreation complex at the Fairgrounds funded with a grant from McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc.

Lipscomb said it is “critical” to have a good relationship with the DOJ because of grant requests on developments and teen handgun violence and other areas.

“There is always the possibility of a shutdown as but one remedy available to many grant-funding agencies,” he said. “It is very draconian, and I would hope never be resorted to.”

He said that, while others weighed in on the issue, “I will take full responsibility for the final recommendation to settle.”

Not surprising, since, as with most of the city’s “big deals” planned for 2013, Robert Lipscomb holds the cards.