Henry Turley is pumped.

Sitting in his office on the top floor of the Cotton Exchange overlooking the river, he is talking about his proposal called Fair Ground to redevelop the Mid-South Fairgrounds. He climbs out of his chair, ignores his ringing cell phone, and punctuates his comments with gestures and “damn rights!” for positive points and unprintable expletives for suggestions of skepticism.

“I think it’s the best idea I’ve had,” says the 67-year-old developer of Harbor Town, Uptown, and South Bluffs, among other projects. (Turley is also a minority stockholder in Contemporary Media, Inc., the Flyer‘s parent company.)

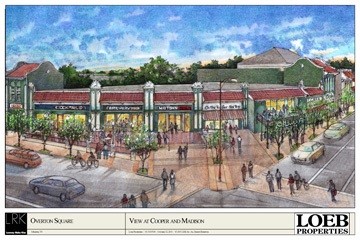

Fair Ground is scheduled to come before the Memphis City Council in early October. In some ways, it is Turley’s most ambitious and possibly most difficult project. The Fairgrounds comes with plenty of baggage, including an aging stadium, a defunct coliseum, and an abandoned amusement park. Fair Ground LLC, a black-and-white gang of seven that includes Turley, Robert Loeb, Archie Willis III, Mark Yates, Jason Wexler, Elliot Perry, and Arthur Gilliam Jr., wants to turn it into a combination of sports complex, renovated stadium, park, and retail center.

In a city where the majority of schools, churches, neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and even sporting events and concerts are predominantly black or white, Fair Ground aspires to create something so special that it will become common ground.

How to do that? In Turley’s words, make Liberty Bowl Memorial Stadium “as good a place for football as AutoZone Park is for baseball and FedExForum is for basketball” and eventually draw an additional 10,000 fans to each game; build a greenspace and grand entrance around the stadium that is “bigger and better” than the hallowed Grove at Ole Miss; add a sports complex modeled after the Salvation Army Kroc Center; and complete a “20 years of education” network of new public schools, Christian Brothers University, and the University of Memphis that is so good it pulls children away from private schools.

All of this is premised on a “clever real estate deal” engineered by Turley that would use taxes from the stadium and new retail stores and hotels to fund public improvements. It is, he says, “the closest thing to alchemy since the Middle Ages.”

Giving Turley his due — no other local developer has his downtown track record or applied to be master developer — the proposal, already 18 months old, has its skeptics.

Mayor Willie Herenton was supposed to sign a development agreement some time ago, but, as of this writing, had not done so. The mayor and his top aide Robert Lipscomb have been preoccupied with the Bass Pro Pyramid deal, the rebuilding of public housing, and now Beale Street. Those projects also rely on special tax streams.

“There are some significant sticking points over the financial terms,” Herenton said in an interview. “I need to be sure that our citizens derive the maximum benefit from this project with minimum exposure.”

Pressed as to what those sticking points are, he said, “It’s all about money.”

Banker Harold Byrd, a big University of Memphis supporter, has said that the Liberty Bowl will never be as well-received as an on-campus stadium and that “people in Knoxville or Oxford would laugh” at the idea of a stadium next to a shopping center.

Former Memphis mayor Dick Hackett, now head of the Children’s Museum of Memphis at the northeast corner of the Fairgrounds, has watched the gradual decline of the area up close. He chooses his words carefully.

“The project would have a profound impact on the environment we work in,” he said. “Retail is interesting and challenging. Whether it is a plus or minus depends on who the retailer is. That’s going to be a hard one.”

Hackett said the Children’s Museum “might as well be closed during football games, because our customers can’t get to it. If there are 11 events a year, then that’s 11 days a year you get beat up pretty bad from a customer standpoint.”

The museum more than defrays the lost business by charging $20 to park in its lot.

Turley is not deterred. When he looks at the Fairgrounds sitting idle in the geographic center of Memphis, he sees only a lot of memories and “200 acres of lost opportunity.”

The stadium and the Children’s Museum still draw crowds, but the rest of the property is demolished, abandoned, or underused. Libertyland amusement park, part of its roller coaster still standing, is closed. So is the Mid-South Coliseum, home to concerts and basketball games in Elliot Perry’s day, before giving way to The Pyramid and then FedExForum. Tim McCarver Stadium was demolished a few years ago, long after it was replaced by AutoZone Park. The annual Mid-South Fair is moving to Tunica, Mississippi, next year. Fairview Junior High School is blighted and has about 300 students. The main feature of the Fairgrounds on most days is several acres of asphalt parking lots.

Turley remembers playing and watching sports at the Fairgrounds in better days. Herenton remembers going to the segregated Mid-South Fair in the 1940s and 1950s, when it was the only opportunity he and other inner-city children had to see a cow or a pig. Two years ago, Herenton proposed replacing the stadium with a new one at a cost of up to $250 million. The proposal died, but Turley was intrigued. What if that kind of money was spent on a modest overhaul of the existing stadium and, more importantly, on the stadium’s surroundings?

“It makes no sense to pour millions of dollars into rehabilitating the football stadium while everything around it deteriorates,” he said.

Then he took another leap. What if the improvements were sports-related but for the benefit of weekend warriors and ordinary people instead of elite professional and amateur athletes? What if Memphians came together as sports participants as well as sports spectators? Could programs such as the Bridges Classic football games that bring together private and inner-city public schools and Memphis Athletic Ministries, which organizes competitive sports for inner-city children on a come-one-come-all basis, be the models for something much bigger?

“The Bridges football games, more than anything else, exemplify what we want Fair Ground to become,” said Turley, a graduate of Memphis University School and the University of Tennessee. “I go to the game, sit down on the Melrose side, and say I’m here on behalf of Fair Ground.”

He also has attended several Southern Heritage Classic games, and he once joined hundreds of angry fans who “stormed the gates” at a UT versus U of M game when an outmanned Liberty Bowl staff tried to funnel them all through one gate, making them miss most of the first quarter. When proponents of women’s roller derby inquired about using a building at the Fairgrounds, Turley quickly took up their cause and attended derby events.

He and others in the Fair Ground group have been meeting for several months with neighbors such as Sutton Mora-Hayes, executive director of the Cooper-Young Community Development Corporation.

“They really have a perspective of how we need something over there that is totally unique,” Mora-Hayes said. “Henry has been pretty open with the neighborhood about what the proposal is. Some ideas have been thrown around, like a Wal-Mart, that I don’t think will happen in a million years. As a neighborhood, we don’t want to say we are against anything on general principles because we are not developers. We have to trust on some level that if Henry is telling us 15 percent of the site is retail to make it successful, then we take that on faith.”

Cooper-Young has a strong group of small stores and restaurants and an annual festival but no park other than a small one near Peabody Elementary School. The neighborhood is racially mixed and most houses sell for less than $225,000.

“I look forward to it [Fair Ground] hosting a mix of ages, races, and sexes,” Mora-Hayes said.

Getting Memphians to come together for participant sports will be at least as hard as financing the project. While the Fairgrounds was deteriorating, suburbs were building super-sized baseball, soccer, and tennis complexes in Cordova, Germantown, Collierville, and Olive Branch, Mississippi. Within 100 miles of Memphis, there is strong competition for regional tournaments from facilities in Jackson, Tennessee, Jonesboro, Arkansas, and Oxford, Mississippi. Parents have become accustomed to hauling their children all over Shelby, Tipton, and DeSoto County for games and tournaments.

There is no multi-sports complex in Midtown, nor is there much in the way of hotels or retailers such as Wal-Mart or Target, which has several stores in the Greater Memphis area, but only one inside the Interstate loop. The rising cost of gasoline and reduced driving could favor the Fairgrounds, as would stronger showings by the University of Memphis football team, which attracts only about 25,000 fans on average to the 62,000 seat stadium.

A lack of customers has led to the closing of retail stores in Peabody Place downtown and the Walgreen’s and a lumber yard next to the Fairgrounds. The downtown elementary school next to AutoZone Park has so far failed to attract many white students. Nobody has to remind Turley. A year ago, his neighbors in South Bluffs were robbed and attacked. The gated entrance on the east side of South Bluffs, which was open previously, is now closed and requires a pass code.

Some misperceptions of the Fairgrounds seem based on opinion rather than evidence. In an interview last week, Herenton predicted that more than 75 percent of attendees at the final Mid-South Fair would be African American. The mayor, who is neither a fair-goer nor a football fan, criticized the fair’s marketing as an example of an outdated view of the world held by his old rival, former Shelby County mayor Jim Rout, now head of the fair. But on three separate Flyer visits to the fair, the crowd appeared to be, if anything, majority white. And Rout was there each time.

Meanwhile, Turley’s team has been asking neighbors and partners what he calls his “Kennedy question,” loosely taken after a phrase from President John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address: What can Fair Ground do for you and what can you do for Fair Ground?

The stakeholders include University of Memphis, Christian Brothers University, the AutoZone Liberty Bowl Classic, the Southern Heritage Classic, Memphis City Schools, and the Belt Line, Orange Mound, and Cooper-Young neighborhoods. Chickasaw Gardens and Memphis Country Club are less than a mile away.

“You can’t have an open discussion if people think you have already come to a conclusion,” Turley said. “We’re going to design this thing to try to help you realize your own dreams.”