If you want to open a can of philosophical worms, watch Olympia.

Leni Riefenstahl filming the famous diving sequences for Olympia in 1936,

I originally decided to add Olympia to my Politics and the Movies series while watching the Olympics. I thought it would be a good way to talk about propaganda, a subject that is more important than ever as we try to sustain democracy in the information age. What better way to approach the subject than tackling the work of Hitler’s favorite filmmaker, Leni Riefenstahl?

Her film Triumph of the Will was presented as a documentary of the 1934 Nazi Party Congress at Nuremberg, Germany. But, seeing as it was commissioned and paid for by the Hitler regime that had, at that point, only been in power for a year, it’s the textbook example of state propoganda. I don’t know if I can really recommend watching Triumph of the Will (I had to watch it in a film class a long time ago), but you’ve seen echoes of the imagery Riefenstahl created to glorify the Third Reich. The final scene of Star Wars, where the heroes are given medals, is a direct lift from Triumph of the Will. In its opening scenes, Hitler arrives at Nuremberg in an airplane, greeted by a hoard of adoring followers. This has been Donald Trump’s MO through much of his campaign. As quoted in the Wikipedia article about Triumph of the Will, Riefenstahl said her instructions from Hitler were, in retrospect, chillingly simple: “He wanted a film which would move, appeal to, impress an audience which was not necessarily interested in politics.”

The iconic long shot of the Nuremberg rally in Triumph Of The Will. George Lucas would later reference this image for the closing scene of the original Star Wars.

Just as today, Hitler was interested in quickly impressing the “low-information voter”. There’s no question that all of Riefenstahl’s work, including Triumph of the Will, is visually beautiful. She had an unerring eye for composition and a strong experimental streak she inherited from the German Expressionist filmmakers with whom she worked as an actress in the 1920s. Triumph of the Will is fascism putting its best foot forward. The appeal of fascism is the natural human urge to belong to a tribe, and for that tribe to be strong. To belong to a tribe means you will be protected, and that difficult questions such as “What is my place in the world?” and “What will I do when I grow up?” have easy answers. Fascism promises to ease the psychic pain of being an individual in a chaotic world.

Riefenstahl’s images of nude athletes were inspired by classical Greek statues.

Hitler and his propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels were so impressed with Triumph of the Will that they commissioned Riefenstahl to create a documentary about the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. The modern games had been going on for 40 years at that point, but no one had ever made a serious attempt at filming them before. Riefenstahl set about the task with typical forethought and attention to detail. One of the many innovations the Nazis brought to the Olympics was the torch relay, and Olympia uses it as a powerful opening sequence to connect the world of classical Greece to the present of 1936.

The torch lighting sequence from Olympia.

Here’s the thing about Olympia: It looks like pretty much every Olympics you’ve seen on television. Or rather, all of the ways you have seen The Olympics on television were invented by Leni Riefenstahl as part of a Nazi propaganda film. She uses slow motion, extreme close ups of the athlete’s faces and bodies, candid footage of competitors warming up and chatting before events, and shots of the crowd cheering for their countries favorites. (The “USA! USA!” chant was already familiar to the crowd, but the one laugh out loud moment for me was a chant by English track and field fans: “We want you to win!”) There’s plenty of rooting for the home team, too. Different cuts of the movie were released in English and French. The cut of Olympia available on YouTube is the original German, and the Nazi athletes are referred to as “our men.” But it’s ultimately much less biased than NBC’s primetime coverage of the gymnastics competitions, where it sometimes looked like the Americans were the only ones competing. Propaganda works because people like it.

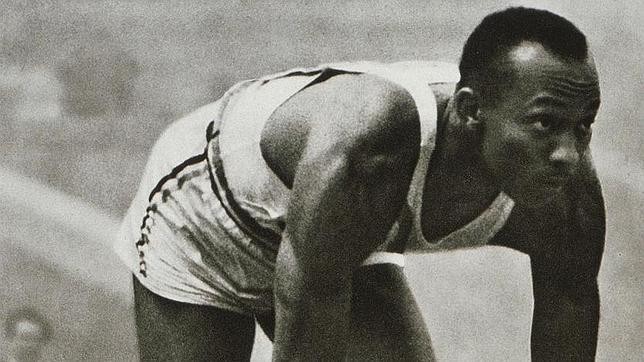

Jesse Owens in Olympia

But Olympia fails at its mission of being pure Nazi propaganda. Hitler wanted the 1936 games to prove his theories of Aryan racial superiority, but he didn’t count on Jesse Owens, one of the greatest athletes who ever lived, and who just happened to be both American and black. In Olympia, Owens doesn’t just win his races, he demolishes the competition in a way not seen again until Usain Bolt took to the track. Riefenstahl doesn’t sugar coat it, even for German audiences. People who have never done any film or video editing don’t realize how much power the editor has. Riefenstahl was working with hundreds of hours of candid footage shot by a small army of cameramen. It would have been easy to pick images of Owens when he was badly lit, or grimacing, or, like NBC did with the non-American gymnasts, just edit him out entirely. Riefenstahl does none of that. It’s clear from Olympia that Owens was the most physically fit person on the field, and he had kind, intelligent eyes and a magnetic smile to boot. Riefenstahl’s camera loves him. And it’s not just Owens. American distance runner John Woodruff won a dramatic 800 meter race with a combination of daring strategy and sheer speed. He was also black. The Japanese won gold and bronze in the marathon. Indians, Africans, South Americans are all represented among the athletic excellence Riefenstahl filmed. The humanist message of the games shines through the layers of attempted propaganda, giving Olympia a remarkable, and perhaps unique, tension.

Jesse Owens prepares to set a world record at the Berlin Olympics.

The examples of beautiful art created by loathsome individuals lie thick on the ground all around us. Pablo Picasso was perhaps the 20th century’s greatest visual genius, but you wouldn’t want your sister to date him. Ezra Pound, who not only wrote incredible poetry of his own but also edited T.S. Eliot, was much more clearly a true Fascist believer than Riefenstahl. Must we throw out “The Wasteland”? In film, there’s Roman Polanski, whose Chinatown is on the shortlist of the greatest films ever made, but who has been on the run from a statutory rape conviction since 1977. Woody Allen is widely admired as a filmmaker, but he had an affair with and ultimately married his adoptive stepdaughter. Does that make Manhattan any less of a film? Right now, the most anticipated film of the fall is Birth Of A Nation, a drama about the Nat Turner slave rebellion that sold at Sundance for the largest amount ever paid for an indie film. When it came to light that director Nate Parker was accused of rape in 2001, and his accuser committed suicide in 2012, the American Film Institute cancelled a scheduled screening. I haven’t seen the film, but if Parker, who was acquitted in a trial, really was guilty, does that automatically mean the film is bad and should not be viewed? Are the Olympics tainted because the techniques and images that made the games an icon of modernity came from a Nazi propagandist? Democracies use propaganda, too, and advertising has perfected the techniques Riefenstahl pioneered. The tools are neutral, it is the purpose to which they are put that matters.

Adolf Hitler and Leni Riefenstahl.

Since I believe that authorial intent is secondary to audience reaction in the creation of meaning, I tend to advocate separating the artist from the art. So what to make of Riefenstahl? If you’ve ever tried to raise money to make a film—or raise capital to start any kind of business, for that matter—you might have found yourself in a situation where you had to decide whether or not to take money from an unsavory character. Filmmakers in the Hollywood system constantly find themselves in a position where they must compromise their visions in favor of their financiers political whims. When I wrote a paper on Riefenstahl in college, I came away with the impression of a woman whose primary motivation was making beautiful images, and who was willing to let the ideological chips fall where they may. But that doesn’t excuse Triumph of the Will. Some bridges are just too far to cross.