Purgatory Gardens

By Peter Lefcourt

Skyhorse Publishing, 240 pp., $24.99

There’s no waiting around in the lobby in Purgatory Gardens. Peter Lefcourt gets right down to business, letting readers know in the first sentence that the Italian wants the African whacked (and first thinks of it as his homeowners association mulls a mold problem in the laundry room).

The book, Lefcourt’s latest crime novel, hits the gas from the jump, pulling readers from page to page with comic realism. But the pace is comfortable, even enough for the book’s past-their-prime cast of characters. It’s less a pedal-to-the-metal thriller and more off-path golf carting (with a chance of murder).

Sammy Dee left the mob and his former life behind when he sang on his boss, Phil “Three Balls” Finoccio. The federal witness protection program relocates him to Palm Springs, California, and the less-than-luxurious Paradise Gardens Condominium Community.

His low-profile lifestyle is upended when he gets his first natural erection in years. On a date at Olive Garden, Sammy glimpsed the “reasonably firm breasts” of his neighbor, Marcy Gray, a “mature” actress. The sight and a whiff of her perfume dilate his downstairs blood vessels without the help of pharmaceuticals.

But Sammy’s romantic pursuits are complicated by Didier Onyekachukwu, a Coastal Ivorian neighbor who also has sights on Marcy. Sammy and Didier have the same idea, the exact same idea. Unbeknownst to the other, they hire the same hitmen to take out the other.

The novel’s publisher, Skyhorse Publishing, describes the book as “Elmore Leonard meets Carl Hiaasen as directed by the Coen Brothers,” and it hits the mark. Purgatory Gardens is hardboiled like Leonard with Hiaasen’s perfectly grimy realism and the Coens’ complex slapstick.

But it ain’t no Father Dowling mystery. “Kike.” “Dykes.” “Wetback.” “Fuck.” “Shit.” “Hard on.” If you don’t like these words, stay away — Lefcourt goes for them in the first chapter.

But if you’re looking for a profane romp with warts-and-all characters looking for nothing close to redemption, you can’t go wrong with Purgatory Gardens.

— Toby Sells

Against the Grain

Bill Courtney (with Michael Arkush)

Weinstein Books, 220 pp., $26

You may be familiar with Bill Courtney. He played a central role — as a volunteer football coach — in the Oscar-winning documentary Undefeated, the story of the 2009 Manassas High School football team. (The title has deeper meaning than a team’s won-lost record.) Courtney has since gained popularity on the motivational speaker’s circuit, all the while running the lumber company — Classic American Hardwoods, Inc. — he started in 2001. Against the Grain (written with Michael Arkush) is a guidebook of sorts, Courtney’s lessons (both taught and learned) on living life true to one’s character, and how to maximize positive influence via character development. It’s a grounded, focused, often-gentle treatise on the two-word mantra Courtney holds dear: Do right.

The author has faced the kinds of adversity that would cripple many, at least emotionally. Courtney’s father left his family when Bill was very young. Only a few years after starting his business, Courtney had to lay off several employees to save the company. (Empathy can be cancerous for a business owner but is required for depth of character.) He even stared at a loaded gun in the hands of a family member. Perspective on “doing right” comes with sharp, often dangerous, learning tools.

“Give credit to those you lead, accept blame when you mess up . . . measure your effectiveness by the success of those you are charged with guiding.” Courtney’s views on sound living (and leadership skills) are shared through the relationships he’s had on the football field, the lumberyard, and his living room. Being fatherless is no excuse for not working, striving, dreaming. The grace of a grandparent can prove to be a stronger influence than the bone-rattling skills of a star linebacker. And each can influence the other. But a solid foundation is required, one Courtney helps define.

Undefeated gained acclaim for the underdog components Hollywood loves (and sells). Against the Grain celebrates the myriad details — many unseen and unheard — that help each of us find victories, small and large, when the bright lights are turned off. — Frank Murtaugh

The Mulberry Bush

By Charles McCarry

Mysterious Press, 320pp., $26

Charles McCarry is not just one of the best writers of spy novels today, he is one of our best novelists period. His The Tears of Autumn and The Better Angels are crackerjack books, mixing action and sociology, riddles and life studies with psychological depth. He’s more lucid than LeCarre and more serious than Ian Fleming. And, as ex-CIA, his details are authentic and his stories sometimes frighteningly realistic. His recurring character, Paul Christopher, is an agent with a heart and has the smarts to master tradecraft and still see clearly enough the foibles of his profession. Sometimes McCarry features Christopher up front, sometimes he’s tangential. In The Mulberry Bush he does not appear.

“Revenge is a dish best served cold,” the maxim goes. The protagonist in The Mulberry Bush, a nameless first person I, seems to understand this in his very marrow. His father was run out of the CIA (Headquarters, it’s called here) and died under mysterious circumstances. He blames Headquarters and, in order to exact revenge, becomes an agent himself. He endures years of training and dangerous assignments, while all the time, within him, his vengeance pearls the grit. He is told, “The fact is, intelligence services exist to commit crimes on foreign soil for the benefit of a government . . . Espionage is a criminal activity, and in every country but their own, spies are felons and worse than felons.” This could serve not only as the exegesis for this plot, but for most of McCarry’s.

McCarry lets his narrative unfold in a slow, cleverly articulated arc. He’s in no hurry because his hero isn’t. The structure is fairly simple; the execution of it is complex and fascinating. The hero’s scheme appears to work to the letter. After many years, he becomes one of the best agents at Headquarters. But, while utilizing his perfect ruse, he crashes into South American politics and drug dealing, a hornet’s nest that seems to engulf his original intentions. To further complicate matters, he falls head over heels in love with a woman deeply involved in the goings-on.

Much of the suspense of The Mulberry Bush is generated by the reader’s ignorance of exactly what form this revenge is taking. The desire to punish an organization as large as Headquarters, rather than any particular individual, seems naïve, even foolhardy. Is our hero stumbling around, or are the diverse machinations of the plot under his control? Who is the puppeteer and who the puppet?

With great gusto, dynamite dialogue, and brilliantly fleshed-out characters, McCarry is the perfect guide, a sly Ariadne in a maze of his own diabolic design.

— Corey Mesler (Corey is the author of Memphis Movie and co-owner of Burke’s Book Store.)

Fates and Furies

By Lauren Groff

Riverhead Books, 400 pp., $27.95

Deep into Lauren Groff’s compelling third novel, where marriage is as much of a character as either spouse, the wife realizes “that there is no such thing as sure. There is no absolute anything.” This knowledge is what makes Fates and Furies such a gripping story — the reader knows what happened between Lotto and Mathilde, but what fascinates is why it happened.

Like Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, Fates and Furies offers readers a bifurcated structure. The first section, “Fates,” examines in chronological order the life of the gregarious Lancelot “Lotto” Satterwhite, heir to a bottled water fortune and destined for greatness. While the second section, “Furies,” uncovers the source of Mathilde’s aloof single-mindedness by alternating stories about her isolated childhood and constructed adult life.

From classic literature, Groff borrows a narrator who channels the Greek Chorus, a cascade of improbable events that befall the protagonists of tragedies (think Hecuba and Oedipus), and the unnerving understanding that mortals may not have control over their own lives. As Mathilde observes during her rumination on sureness, “the gods love to fuck with us.”

Missing from Fates and Furies is the delightful liberties Groff took with realism in her earlier collection of short fiction and first novel, The Monsters of Templeton. However, by replacing the fantastical with the mythological, she resurrects catharsis — that is, lets the reader vicariously purge their failures when Lotto fails, and their grief with Mathilde’s grief.

Already well-lauded (Amazon just named Fates and Furies its book of the year), this novel deserves as many readers as Gone Girl. And yet, it deserves more because, unlike more traditional page-turners, a reader of the Möbius strip that is Fates and Furies is likely to reach the end of the novel, land on the last word, “sure,” and be unsure enough about the whys of Lotto and Mathilde to begin again.

— Courtney Miller Santo (Courtney is the author of The Roots of the Olive Tree and Three Story House.)

Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink

By Elvis Costello

Blue Rider Press, 674 pp., $30

Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink by Elvis Costello is a book about show business. It can be said that Costello’s career didn’t begin with the release of 1977’s My Aim Is True, but when Costello, as a young boy, accompanied his father to the Hammersmith Palais in London where he worked as a crooner with the Joe Loss Orchestra. Show business is the MacManus (Costello’s given name is Declan MacManus) family business. It was in the darkened ballrooms of his youth that Costello first learned not only how to hold a note but how to hold an audience. More than merely getting up on stage to belt out a tune, he learned about persona and character, conveying a story or emotion, and engaging a crowd. Such a life is Costello’s birthright.

He shares his life with us through stories woven together over time and geography (this book is nonlinear, so while you might begin a chapter in Arizona in 1978, you may soon find yourself in 1969 Liverpool), and throughout we are schooled in the history of popular music. For anyone who thinks they know their early British rock music, Costello is here to assure you that you do not.

He came on the global scene in 1977 and his namesake, Elvis Presley, would perish within months of the release of Costello’s first album. He walks us through the recording, rehearsing, marketing, and touring of that album and subsequent albums with anecdotes that read like a true rock-and-roll show — quick and raucous. He writes about those in the industry he looks up to and has played with and admires still, and just a few he never cared for at all.

But the most introspective stories are saved for his family and especially the illness and recent death of his father, whose presence was a beacon for Costello throughout his life. It’s just the sort of emotion and feeling he’s put into four decades of music, and it’s that connection with the reader that makes a great entertainer and a great book.

— Richard J. Alley

City on Fire

By Garth Risk Hallberg

Knopf, 944 pp., $30

It’s New York, late ’70s. A 17-year-old girl is shot in the head in a park near a swanky building. Within that building is a party and within that party are two unhappy attendees who are connected, if somewhat distantly, to the girl. The plot of Garth Risk Hallberg’s City on Fire revolves around that girl and various other persons (punks, a journalist, a detective, a millionaire’s son and daughter, a teacher and writer, someone aka-ed the Demon Brother, and other hangers-on), and together they populate a certain New York of a certain time.

Hallberg was famously offered a $2 million advance for City on Fire, his debut novel and his attempt, reportedly, to capture ’70s-era NYC the way The Wire did with Baltimore. As for whether it does succeed in bringing that turbulent time back to life, I’m too young to remember (as is Hallberg). It does seem a certainty that Hallberg used Patti Smith’s Just Kids as a reference. (It’s a charming, evocative memoir. Pick it up for the ambience.)

Epic, ambitious, and sprawling are the words that come to mind, which is another way to say that the book is long as hell — 900 pages-plus. The first bit spins along promisingly; there’s hope and rebellion and rejection of mores. There are great paragraphs, hundreds maybe, throughout that read like clouds of art: “And you out there: Aren’t you somehow right here with me? I mean, who doesn’t still dream of a world other than this one? Who among us — if it means letting go of the insanity, the mystery, the totally useless beauty of the million once-possible New Yorks — is ready even now to give up hope?”

But all that art tends to gum up the narrative. There’s just so much of City on Fire — little action compared to the pondering and the backstories and the facsimiles of letters and ‘zines — it can be hard to keep up, and while I know what happens in the end, I can’t say for certain as to why it happens. — Susan Ellis

Black Wolves (The Black Wolves Trilogy)

By Kate Elliott

Orbit, 817 pp., $15.95

To most people, epic fantasy stories evoke a particular set of themes: ancient, powerful races, kingdoms at war, struggles between good and evil, mythical creatures, and damsels in distress.

Kate Elliot’s Black Wolves contains quite a few of these elements, but Elliott masterfully deconstructs them, giving us a fresh new take on epic fantasy. The story of Black Wolves centers around five point of view characters: Kellas, one of the eponymous Black Wolves, who serves as a royal assassin and spy; Dannarah, daughter of the legendary King Anjihosh, who slayed corrupt demons and brought law to the Hundred; Sarai, a disgraced young woman from a wealthy people who enters into a political marriage; Gil, a disgraced young man from a scorned family who must marry Sarai; and Lifka, a young woman whose life changes after she steps up to save her father from an act of injustice.

Each of those hallmarks above deals in some sense with power — who has power, who wants power, and how this power plays out among the powerless. Power in Black Wolves manifests itself not as magical ability, but as political might — as taxes and political alliances and rule of law, as bloodlines and cultural upheaval. Elliot examines and then uproots our expectations of how this power is expressed using deft weaves of characterization, worldbuilding, and narrative twists that will stun readers.

Black Wolves is a brilliant piece of epic fantasy, and one of the best books I’ve read all year. The timeskip at the beginning of the book seems out of place at first read, but the payoff is definitely worth sticking around for.

And if that’s not enough to sell you on Black Wolves, stick around for the giant eagles. — Troy L. Wiggins (Troy’s story “Tell Him What You Want” appears in the Memphis Noir anthology.)

Memphis Man: Living High, Laying Low

By Don Nix

Sartoris Literary Group, 220 pp., $19.95

Memphis Man is the autobiography of Don Nix, the Memphis music producer and all-around rock-and-roll raconteur who worked in one capacity or another with artists like Eric Clapton, George Harrison, John Mayall, and Isaac Hayes. At just over 200 pages, Nix begins Memphis Man by describing a unique time for rock-and-roll in Memphis, a time when Elvis was performing at places like Messick High School and Dewey Phillips ruled the airwaves with his nightly Red Hot and Blue show. Memphis Man is an incredibly thorough look at Nix’s life, chock-full of wonderful stories and photographs that feature legendary musicians like Elton John, Carla Thomas, and Albert King.

Although the majority of the book reminisces on the glory days of Memphis music and what it was like to tour in a Memphis band, the clarity with which Nix tells his stories is spot-on, making the reader feel like these events took place only days ago. His story of meeting Freddie King at Chess Records in 1970 is one of my favorites, especially when he recalls performing the song “Palace of the King,” a song that Nix and Leon Russell wrote for King. The group worked on “Palace of the King” for three or four days, “stopping only to order fried chicken from Fat Jack’s.” Maybe that’s the best part of Memphis Man: the lack of pretense gives the reader an immediate feeling of relating to the author. This isn’t some heady, word trip written by a god of Memphis rock-and-roll, but instead reads like a long-lost diary, leaving the reader with a great sense of just who Don Nix really was back in his glory days.

— Chris Shaw

The Witches: Salem, 1692

By Stacy Schiff

Little Brown and Company, 498 pp., $32

Author Stacy Schiff’s The Witches is an exhaustive work on the history of the Salem witch trials. This is The Witches in a nutshell: Puritan ‘tween girls start acting crazy, interrupting prayers, convulsing, and writhing about — you know, typical teenage girl behavior. The bratty girls call out some random nice church ladies and accuse them of “afflicting” them with their evil witchcraft. Nice church ladies are all, “I’m not a witch! I’m a nice church lady!” And the girls are all, “Are so!” And the church ladies are all, “Am not!” And then, the preachers get involved, and they’re all, “She’s a witch! Burn her!”

Okay, just kidding about that burning part. All 14 of the women accused of witchcraft who were executed in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1692 were hanged. But you get the idea — just a bunch of minister dudes taking the word of teenage girls as gospel. It’s tragic and fascinating, and it leaves one to marvel at just how far we’ve come from our Puritanical, fundamentalist ancestors, for whom every facet of daily life revolved around religion.

Schiff won a Pulitzer for her biography on the life of Cleopatra, so I had higher expectations for the readability of The Witches. It’s an incredibly comprehensive work, considering that records of that time in American history are scarce. And I’m certain Schiff may have written the most exhaustive text on the Salem witch trials ever penned.

But there are so many characters — accused witches, their accusers, authority figures, ministers, servants, townspeople — and Schiff jumps seamlessly from one person’s story to the next. It’s hard to follow what’s going on, and I felt like I needed a flow chart to keep all the Williams and the Marys and the Johns straight. To top it off, Schiff attempts to spice things up with a flowery style of prose that, at times, left me completely clueless as to what I was reading.

That said, for anyone seriously interested in the history of witch trials in America, The Witches is probably the only book out there with the full story. At times, it’s more textbook than anything else. But if you can focus hard on what you’re reading, you’ll come away all the wiser.

— Bianca Phillips

The Vanishing Island (Chronicles of the Black Tulip)

By Barry Wolverton (Illustrated by Dave Stevenson)

Walden Pond Press, 352 pp., $16.99

The Vanishing Island is the first installment of local author Barry Wolverton’s new Chronicles of the Black Tulip series (his previous novel is the stand-alone Neversink, 2013). Set in the fictional town of Map on the coast of Britannia in 1599, the book combines alternate history, Dutch and Chinese folklore, and high-seas intrigue to create a rollicking adventure story the likes of which we have not seen in a while. Bren Owen is a young boy who feels doomed to a life of drawing maps instead of using them to travel the world, and his thwarted attempts to escape that fate only bind him more tightly to it.

Sentenced to work in the vomitorium (yes, it’s just what it sounds like) of the cruel mapmaker Rand McNally’s prestigious adventurer’s club, Bren encounters a dying stranger who entrusts him with a mysterious engraved coin. Bren’s wildest dream comes true when he receives an invitation to sail on The Albatross, the insignia ship of the famous Dutch Bicycle and Tulip Company, by the ship’s Admiral. He quickly befriends the ship’s boy, a small Chinese orphan called Mouse. But there is more to the handsome Dutch Admiral and his ship’s boy than Bren could have imagined, and not all of it is good.

Peppered with gross-out details and bits of gory violence, this book has more to offer boys than most popular titles for this age group. However, readers of all ages and genders will enjoy rooting for Bren and Mouse as they navigate treacherous adults and mystical destinations. — Kristy Dallas Alley (Kristy is the librarian at Northside High School)

Mislaid

By Nell Zink

Ecco, 256 pp., $26.99

In Nell Zink’s wry sophomore novel Mislaid, life in a small college town in Virginia isn’t as picturesque as the movies might have portrayed. Zink creates a satirical world populated by off-kilter characters with irrational motives and complex identities in a time when white America’s homogeneity seemed most stable.

Bear with me as I lay out the plot: Peggy, a closeted lesbian who also struggles with gender identity issues, is a 17 year old who doesn’t fit the mold of a prim Southern lady. She’s forced to marry a haughty gay professor named Lee after an affair leads to an unplanned pregnancy. Despite her husband’s ongoing affinity for men and her own struggles being branded “butch,” Peggy attempts and fails to live the American Dream with her philandering husband. One day, their unusual and unhappy relationship ends when Peggy runs away with her youngest child. Fearful that she will be committed, Peggy, Caucasian and blonde, adopts the identity of a dead African-American woman, and she and her daughter live a secret life in poverty until circumstances reunite the family many years later. The story alternates between Peggy in her newfound identity as a poor black woman and Lee’s intellectual endeavors fueled by narcissism. The turmoil she faces is passed on to her daughter, who must live a life of a pariah in a small Southern town because of her fraudulent identity. Confused? In Zink’s strange world, it all makes sense.

In an age of Caitlyn Jenner, Rachel Dolezal, and the #BlackLivesMatter movement, the book is very timely. I’d imagine Zink received a high five from her editor when the Dolezal story broke earlier this year. The book’s themes will resonate with modern audiences despite the time period of the story, and Zink’s emotionless, deadpan descriptions of racial and social inequality are refreshingly honest.

Zink’s writing is zany and cerebral with a witty matter-of-factness that only heightens the weirdness of the world she creates. In about 250 pages, Zink is able to address issues of family, race, class, and sexual and gender identity. The thematic brevity is matched only by her ability to craft precise emotionally complex scenes. With varying shades of a Shakespearean comedy of errors and a Faulknerian Southern gothic, her prose is both accessible and highbrow. While Zink’s voice may not be for everyone, this should be considered one of the most wonderfully relevant books of 2015. — Kevin Dean (Kevin is the executive director of Literacy Mid-South.)

The Future Belongs to Students in High Gear

By Amy D. Howell & Anne Deeter Gallaher

Gallaher/Howell, 184 pp., $15

For teens entering college or preparing for the work world, PR professionals Amy Howell and Anne Deeter Gallaher provide a handy roadmap, sharing advice on how to develop your A-game for life. They speak from experience. Each heads up their own marketing and public relations firms; Memphis-based Howell is the CEO of Howell Marketing Strategies, and Gallaher heads Deeter Gallaher Group LLC in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Both have walked this path themselves — while Gallaher’s kids are launched, Howell has her two teenage sons preparing for this important life passage.

The pair taps their own vast networks to include feedback and personal experiences from professionals on a variety of subjects that are woven throughout each chapter. The topics they cover — and the insights they provide — are beneficial. They discuss one’s digital footprint, the importance of a well-developed resumé, why personal drive matters, and making good choices in college, among others.

Some of what they write may seem apparent to adults, but perhaps not as much to young people. One example is the digital footprint students leave online and how those snarky Twitter remarks and Saturday night kegger photos on Instagram may say much more about where your teen’s priorities lie than the volunteer work they mention on their resumé.

Their point is that in order to be in high gear for the career path that lies ahead, one must be strategic in how life is conducted during the college years. Words, tone, accuracy matter — on resumés and in life. This is a book that guidance counselors and parents will want to slip under the door of their teen’s bedroom.— Jane Schneider

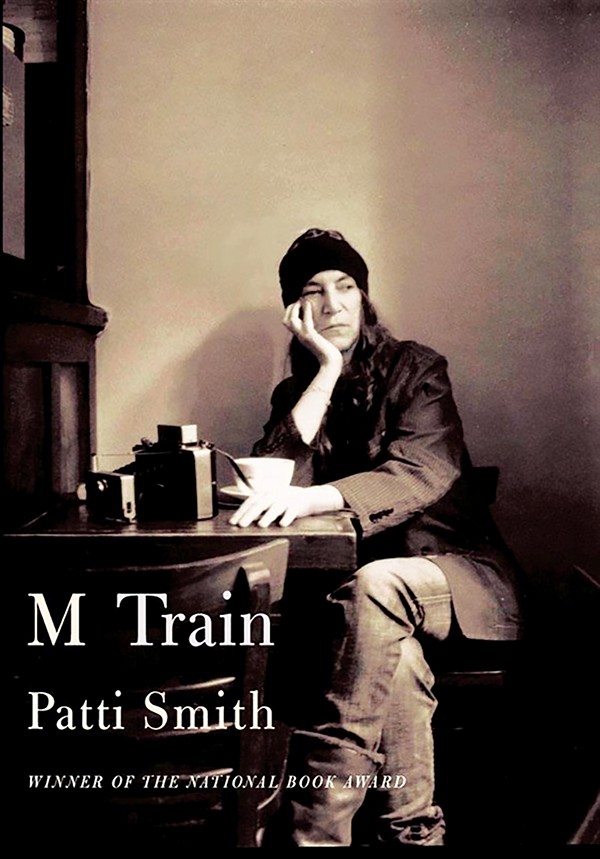

M Train

By Patti Smith

Knopf, 272 pp., $25

Patti Smith’s M Train is a dreamy reflection on the artist’s extraordinary life. Loss is the predominant theme of this gauzily mystical memoir that isn’t so much far out as it is familiar to anyone who has contemplated the ephemeral and elusive nature of memory and dreams. Smith’s prose seamlessly evokes a reverential and often melancholic atmosphere for the reader as she jumps around in time, reminiscing about her travels, her deceased husband, and the pursuit of coffee. A woman truly dedicated to caffeine, pilgrimages are undertaken to cafés from Tunis to Veracruz, where William S. Burroughs said the best beans in the world are grown.

More than anything, M Train relays Smith’s passion for literature, which, in addition to the perfect cup of coffee, is revealed to be the underlying impetus, and sometimes MacGuffin, for so many of her travels and adventures. A desire to visit Genet’s favorite prison results in a trip to French Guiana, an obsession with Murakami leads her to Mexico City, the details of which all strike the right balance between whimsy and melancholy, purposefulness and randomness.

M Train begins, ends, and is interspersed with a particular reverie involving a Lynchian, Stetson-wearing cowboy who delivers the advice, “It’s not so easy writing about nothing.” Easy or no, Smith makes art out of her introspection and creates a powerful mood of melancholy with her meditations. — Jenny Bryant