Kits to help prevent and stop opioid overdoses are free in Shelby County until supplies run out.

The Shelby County Health Department (SCHD) is distributing the kits at select sites (see below) on a first-come, first-served basis. The kits contain two doses of nasal-spray naloxone (known as Narcan by its brand name), 10 fentanyl test strips, and instructions for each.

SCHD Health Officer Dr. Michelle Taylor said the kits are being distributed “to save lives.”

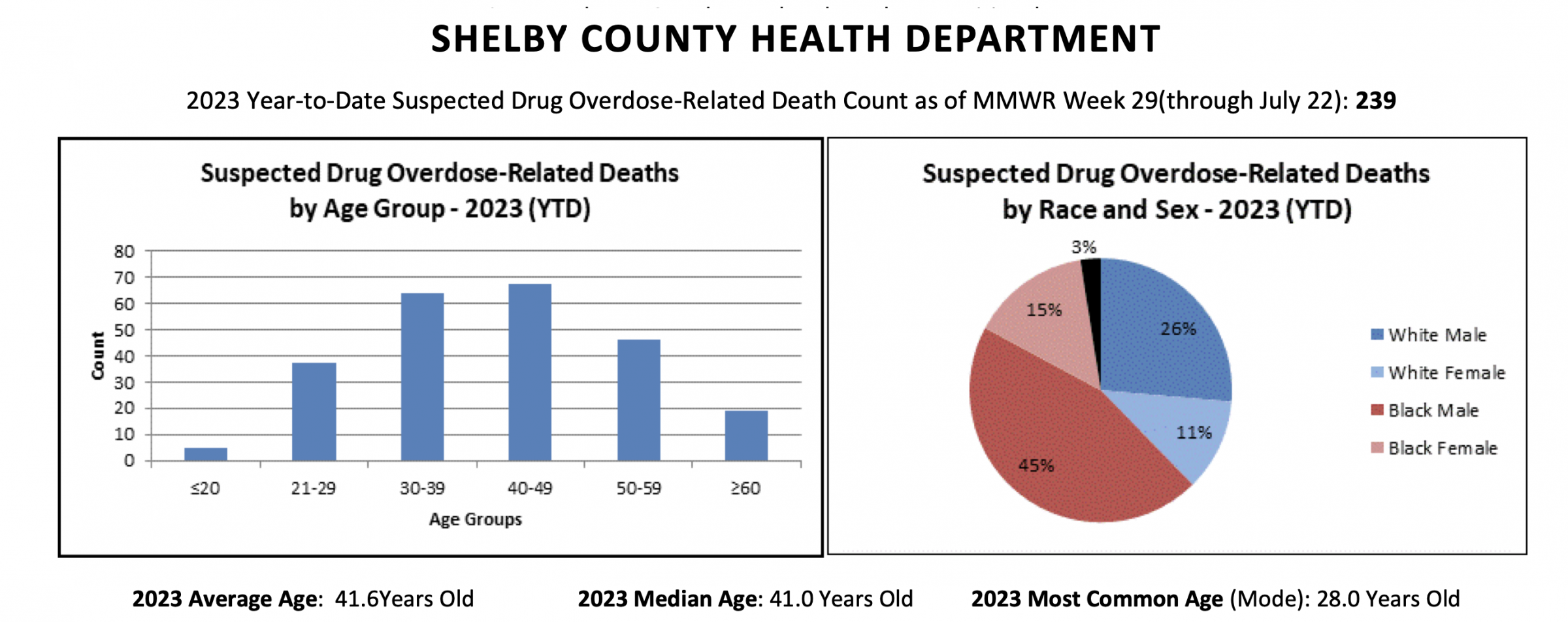

“From 2018 to 2020, overdoses killed more people in Shelby County than automobile accidents,” Taylor said in a statement.

The program is a partnership with the Tennessee Department of Health (TDH), which says naloxone is “a proven tool in the battle against drug abuse and overdose death.”

“When too much of an opioid medication is taken, [the opioid] can slow breathing to a dangerously low rate,” reads the TDH web page on naloxone training. “When breathing slows too much, overdose death can occur. Naloxone can reverse this potentially fatal situation by allowing the person to breathe normally again.”

The state says naloxone is not “dangerous medicine.” But state law does require proper training to give the drug and be covered against civil lawsuits. In 2014, the Tennessee General Assembly passed a Good Samaritan Law that give civil immunity to those administering the drug to someone they “reasonably believe” to be overdosing on an opioid.

To get the required training, the state offers an interactive online course here and a read-through version of the class here.

After the review, trainees must pass an online quiz available here. Once complete, trainees can then add their name to a printable certificate found here.

Regional Overdose Prevention Specialists (ROPS) offices are located throughout the state of Tennessee. They are the point of contact for most opioid overdose training and the distribution of naloxone.

The state says more than 450,000 units of naloxone have been distributed through ROPS from October 2017 to March 2023. In that time, state officials have documented at least 60,000 lives saved with naloxone, a number that’s likely higher “because of stigma and other factors.”

State Sen. London Lamar (D-Memphis) wanted to make naloxone even more widely available in this year’s legislative session. Her bill would have mandated that some bars (selling more than $500,000 worth of alcoholic beverages per year) keep naloxone on premises as a condition of keeping their liquor-by-the-drink license.

The legislation was similar to New York City’s “Narcan Behind Every Bar” campaign. But Lamar’s bill was never fully reviewed and stalled in the committee system.

Fentanyl test strips were illegal in Tennessee until last year. Possession of such strips were a Class A misdemeanor and distribution was a Class E felony. But lawmakers made them legal to fight opioid overdoses when Gov. Bill Lee signed a bill into law in March 2022.

To use the strips, small amounts of drugs are mixed with water. The strips are dipped into the solution for 15 seconds. Then, the strips produce colored bars to signal whether or not the sample contains fentanyl or if the test is inconclusive.

In 2018, researchers found that some community groups across the country began to distribute fentanyl test strips. At the time, they found that most (81 percent) drug users who got the strips, used them. Some (43 percent) changed their drug-use behavior because of the strips and most (77 percent) said they were more aware of overdose safety by having the strips.

Those kits with naloxone and the fentanyl test strips are available from 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. at

• SCHD headquarters

814 Jefferson Avenue

• Cawthon Public Health Clinic

1000 Haynes, 38114

• Hickory Hill Public Health Clinic

6590 Kirby Center Cove, 38118

• Millington Public Health Clinic

8225 Highway 51 North, 38053

• Shelby Crossing Public Health Clinic

6170 Macon Road, 38133

• Southland Mall Public Health Clinic

1287 Southland Mall, 38116

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  DEA

DEA