Given how fast and complete the fall from power of the Tennessee Democratic Party has been, the fact that the state’s Democrats in 2014 actually have a contested primary for a major statewide office — Terry Adams vs. Gordon Ball in the U.S. Senate race (see “Politics,” p. 12) — is more than remarkable.

Almost as remarkable as the fall itself. This is a party, after all, whose control of state government was reasonably secure from the end of Reconstruction until well into the current century. There had been challenges from the Republican Party, to be sure — beginning in the mid-1960s, when tensions between pro- and anti-Clement factions allowed the election of Republican Senator Howard Baker, who was followed into statewide power by Governor Winfield Dunn and Senator Bill Brock.

There were GOP stirrings in the legislature, too. But Richard Nixon’s Watergate scandal tamped things down a bit, in Tennessee as elsewhere. And arguably it was only the Nixonesque follies of scandal-ridden Democratic Governor Ray Blanton that allowed the two-term gubernatorial interlude of Republican Lamar Alexander.

The GOP got another bounce in 1994, with the election of Senators Bill Frist and Fred Thompson and Governor Don Sundquist, but this was at most a bellweather period for Tennessee, with the balance between the two major parties corresponding to that in the nation at large.

In any case, Tennessee Democrats had control of the governorship, the state’s congressional delegation, and both chambers of the General Assembly as recently as 2006.

That was then, this is now, when, in the estimation of state Senator Reginald Tate, the Memphian who aspires to be the next Senate Democratic leader, the Democratic Party may have five members to start the forthcoming legislative session.

“Man, we could have caucus meetings in my car,” says Tate, who lost his first bid for leader in 2013, by a vote of 4-3, to fellow Memphian Jim Kyle, the Senate Democrats’ traditional caucus head and a leading candidate for Chancery Court this year.

There were seven Senate Democrats in the 2013-14 session, out of a total of 33, and the party’s House delegation numbered 28 of the chamber’s 99 members.

So what happened? Like the rest of the South, Tennessee began drifting toward the GOP at about the time, paradoxically, when the Democratic Party, long the party of middle- and working-class whites, began to expand its mission to people of color, to women, and to a variety of other erstwhile heterodoxies.

For a while, that process swelled and sustained the Democratic coalition, but at some point the white middle class — the male part of it, especially — began to make common cause with the well-off constituencies (“job creators” in the jargon of today’s conservatives) who had always constituted the core of Republicanism.

Wealth is, after all, just one kind of status quo. “Values” voters had something to hang on to, as well. Most of the latter never quite got out from under economic duress — especially in the costlier new suburbs to which they retreated in an effort to rekindle the ever-eroding homogeneity they had been used to. They discovered that they, too, like the traditional businessmen and industrialists of the old GOP, resented the hell out of taxes, which they increasingly saw as destined to support unfamiliar ethnicities and radicalisms. Hence the rabid distrust of government by the Tea Party, that bloc of right-wing populists whose New Deal ancestries still survive in their hatred of big-bank bailouts.

There were other triggers along the way. The Tennessee Waltz prosecution of local and state governmental figures mid-way through the current century’s first decade netted Democrats disproportionately — either incidentally or, as skeptical Democrats eyeing the Bush-era Justice Department might imagine, on purpose.

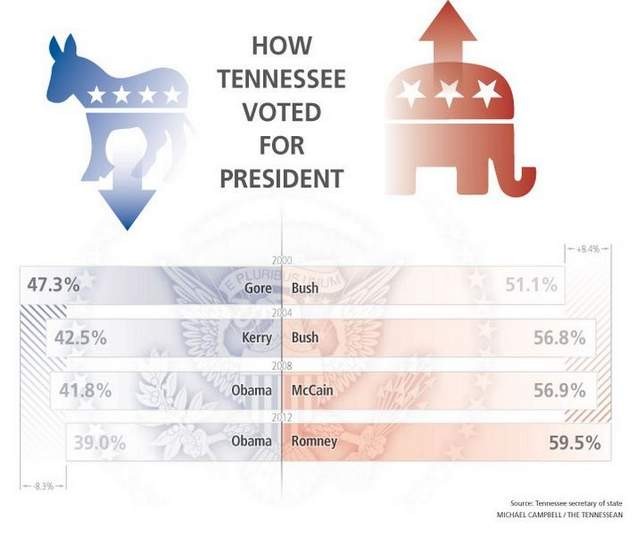

Then there was the presidential election of 2008. Barack Obama’s nomination and subsequent election may have been a triumph for progressivism and the American dream, but what remained of a coherent Democratic power structure in Tennessee had been loyal to Hillary Clinton, and her defeat in the national primaries left it in shambles — a circumstance made worse by the Obama-Biden ticket’s disinclination to campaign in Tennessee or to channel significant funds to the state party.

In 2008, the state House joined the state Senate in electing a Republican majority. And in 2010 — a political off-year on steroids — Democratic candidates were engulfed by a newly indigenous Tea Party wave. And 2012 — ironically the year of another Democratic victory nationwide — saw the Democratic Party in Tennessee, pitilessly gerrymandered, authentically unpopular, and afflicted by self-doubt, virtually eliminated.

So here we are.

Jackson Baker is a Flyer senior editor.