We’ve planned this cover for a couple of weeks, calling on sources, digging through social media, and going to rallies and marches to find the faces of Memphis resistance. Turns out, all we really had to do was check with City Hall. The city of Memphis has a list.

The Commercial Appeal‘s Ryan Poe uncovered the Memphis Police Department’s “escort list” through an open records request and revealed it in a story Friday. The list features the names of dozens of Memphis activists, organizers, disgruntled former employees, and others. Those on the list “have to be escorted inside City Hall at all times,” according to a note on the list signed by MPD Lieutenant Albert Bonner.

Mayor Jim Strickland said he hadn’t seen the list before Poe’s story surfaced and said he will review it with MPD director Michael Rallings to discuss its future.

“It is the professional assessment of the Memphis Police Department’s Homeland Security Bureau that individuals on the list pose a potential security risk,” Strickland said in a statement, Saturday. “It’s important to note that these individuals have not been banned from City Hall. They simply require an escort.”

Citing ignorance of the City Hall security list is one thing, but we do have insight into how Strickland handles protests. When Greensward supporters took to the grassy field in Overton Park last April (armed with protest signs, streamers, guitars, and kids in costumes), Strickland ordered 88 security staffers (including MPD, Memphis Fire Services, Memphis Animal Services, and more) to the site. The show of force included clandestine surveillance units, mounted police, a fleet of police cruisers, and a cop chopper circling overhead. All of this cost taxpayers around $37,000.

A few months later, about 1,000 protestors shut down the Hernando de Soto Bridge in an action aimed at drawing attention to the deaths of several black men at the hands of police across the country. MPD officers, and Rallings, himself, ensured that protestors marched peacefully and safely through downtown streets and onto the bridge. Once there, they were met with a sea of blue lights, a squad of cops clad in black riot gear, and a police helicopter.

Both protests ended peacefully, and the overwhelming police presence may have had something to do with it. The City Hall list, though, feels like overreach — targeted and possibly aimed at intimidation.

The original introduction to this piece described a city that lauds the efforts of its resistors. We paint their faces 15 feet high on the sides of buildings and call them “Upstanders.” We turned the site of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s final moments into the iconic National Civil Rights Museum, which helps visitors and locals alike learn about what King and other civil rights leaders fought and died for. Through that lens, we’ve watched with some pride as grassroots efforts in Memphis have sprouted and grown since the inauguration of President Donald Trump. If any city is going to respect those who rise up and resist, it should be Memphis.

Maybe future generations will paint visages of the new resistance on another Upstanders Mural, like the one in South Main. Though the spectrum of resistance and activist groups in Memphis is wide and diverse, we’ve selected a few to highlight. Memphis, meet (some of) the resistance. — Toby Sells

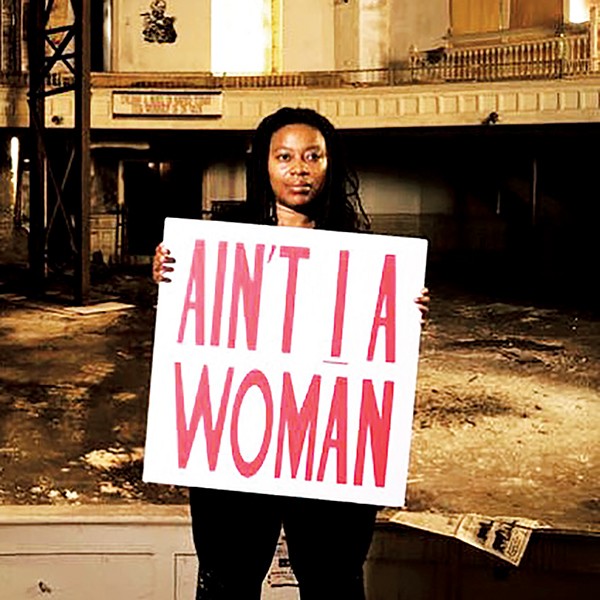

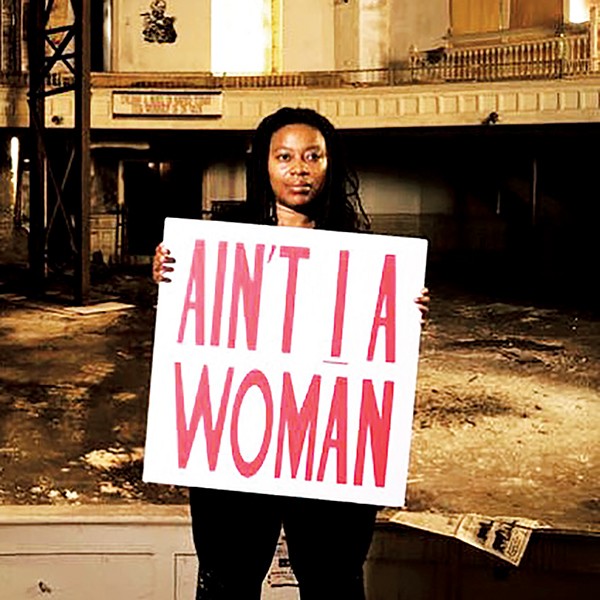

Black Lives Matter, Memphis Chapter

Perhaps the most recognizable of the social justice-oriented groups, Black Lives Matter faces ample scrutiny from law-enforcement supporters and, well, white people, though there has never been an “Only” in front of the group’s name.

BLM as a national organization formed after the death of Trayvon Martin, the unarmed Florida teenager stalked and killed by George Zimmerman, a self-proclaimed neighborhood watch vigilante. BLM has grown in size and reach, often in conjunction with protests against police killings of unarmed African Americans.

Shahidah Jones, a Memphis chapter representative, says that people’s involvement in the Memphis chapter tends to rise and recede. “It’s not a growing trend, necessarily, but people will be motivated by a particular incident and come out,” Jones says, adding that “it really depends on public traction, but also accessibility.”

Joey Miller

Joey Miller

with Black Lives Matter

In this case, accessibility refers to how much time someone is able to commit to BLM, which is why the chapter is comprised of regular members who stay steadily involved, like Jones, and volunteers who can help organize around a specific event.

“The basic core of what we’re doing is we are fighting for the liberation and equality of all black people,” said Jones.

Like most social justice groups organizing under a national presence, the local group adheres to national guiding principles. For BLM locally, the economic equality they are pursuing has many components. This year, the chapter decided that pursuing transformative justice in Memphis means working on bail reform and decriminalizing marijuana — two components of the criminal justice system that disproportionately work against people of color.

Jones advises anyone wanting to get involved with BLM Memphis to send an email and let organizers know how they would be able to contribute in terms of time and skill set. — Micaela Watts

Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ)

As more and more community activism takes aim at dismantling long-standing institutional structures — and centuries-old repercussions — on people of color, there’s a call for white individuals to join in efforts to fight racism.

For many whites, answering that call is not always a clear-cut process, particularly when it comes to grassroots movements. How to combat racism without being, well, kinda racist isn’t always clear to the race that has been at the top in this country since its founding.

SURJ exists to engage white people who want to dismantle racism. Like Black Lives Matter, SURJ is a national organization, and the Memphis chapter formed in the latter half of 2016.

Micaela Watts

Micaela Watts

of SURJ

Allison Glass, one of the representatives of the group, said the catalyst to the Memphis chapter’s formation came in July, shortly after more than 1,000 people shut down traffic on the I-40 bridge.

“It was such a powerful moment in Memphis that I think people felt really inspired,” says Glass. “If these folks are going to commit such a courageous act, then we as white people need to organize other white people to join this effort.”

In September, SURJ members dispersed through the crowds of the Cooper-Young Festival in their first action and signed up people interested in learning how to combat racism. They also sold Black Lives Matter yard signs, with the proceeds going to the national BLM organization.

“One of the core principles of SURJ is about accountability, specifically to people-of-color-led organizations. So, SURJ signed on as an organizational partner to BLM,” says Glass.

Like many community organizing groups, the interest in SURJ has risen following the election of President Trump. The organization will host its next direct training action on March 4th at Evergreen Presbyterian Church in Midtown. — MW

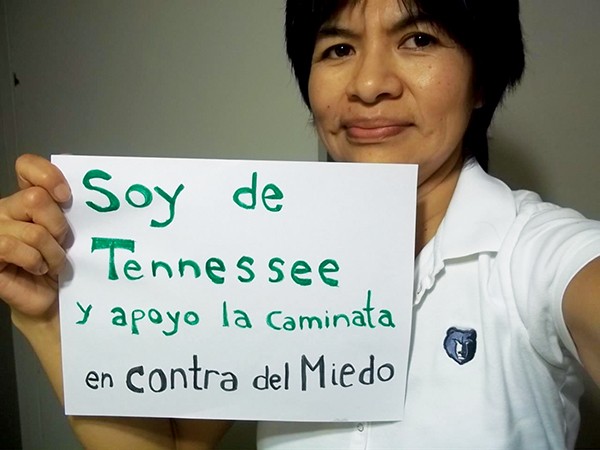

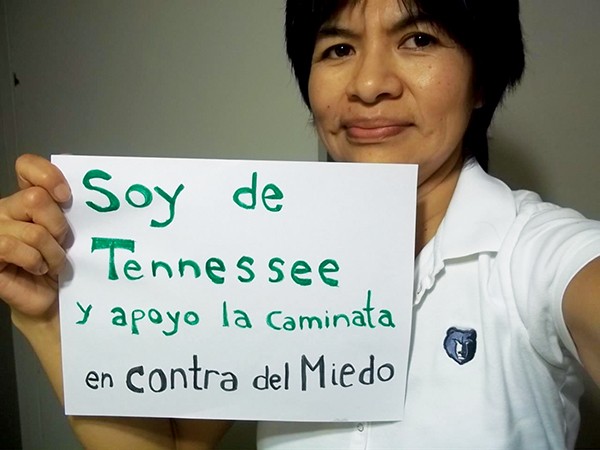

Comunidades Unidas en Una Voz

Though the Memphis chapter of Comunidades Unidas en Una Voz (United Communities in One Voice) formed in 2010, it made local headlines after organizing the 3,000 strong Memphis We Belong Here march on February 1st, in downtown Memphis.

“We never imagined the magnitude that this march would have and all the support we have received from people,” says CUUV organizer, Christina Condori.”The actions are a response to the erroneous measures being implemented that hurt our families,” she adds.

The erroneous measures Condori refers to may have come into the spotlight after President Trump’s travel ban, but CUUV has been rallying against the lesser-known immigration practices that have been dividing families in the Mid-South for years.

Christina Condori, an organizer with CUUV

They’ve called upon Shelby County officials to not work with ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement) in executing raids in Spanish-speaking communities, where individuals often do not know their rights as undocumented residents in Memphis.

“When there was a raid and people did not know their rights, we started attending TIRRC (Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition) workshops and would then transfer the learned information regarding our rights,” Condori says. CUUV has started hosting “Know Your Rights” workshops in churches, schools, and businesses within vulnerable communities.

CUUV has aligned with multiple organizations on the local and national level, including Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ-focused groups, and Fight for $15, the national living wage reform group. The diversity among their affiliated causes is linked to a core tenet, “No to xenophobia.”

CUUV plans to continue organizing against policies that harm minority communities and will strive to make Memphis a place that welcomes immigrants and refugees. “We know we are not alone,” says Condori. “We have many allies who are willing to support us.” — MW

Protect Our Aquifer

Ward Archer is no stranger to matters of the environment and public interest. Several years back, he helped raise $4 million to buy endangered property along the Wolf River from would-be loggers on behalf of the Wolf River Conservancy.

In the process, Archer ended up well grounded (in every sense of that term) with the fact that the headwaters of the Wolf — the Baker’s Pond area in northern Mississippi — served as a recharge area for the Memphis Sand aquifer, the source of Memphis’ unusually pristine drinking water. Fascinated, Archer learned everything he could about the subject of ground water in general and the Sand aquifer in particular.

Archer, who is also a board member of Contemporary Media, Inc., the Flyer‘s parent company, remains sensitive to any news regarding the aquifer and responded to the alarm raised last year by Scott Banbury of the Sierra Club about what had been a virtually unpublicized plan by the Tennessee Valley Authority to do some massive drilling into the aquifer to acquire coolant water for TVA’s forthcoming natural-gas power plant.

Banbury and experts like Brian Waldron, of the University of Memphis, made a compelling case that the drilling — five wells, three of them already approved and some of them arguably ill-placed — could result in possible contamination of the aquifer’s water supply.

Archer formed an ad hoc non-profit citizen’s group, Protect Our Aquifer, which has held numerous public meetings to raise awareness of the issue and has participated in various actions to halt the TVA drilling. The group has joined the Sierra Club in an ongoing legal appeal, now in Chancery Court, to reverse the preliminary approval of the TVA drilling by the Shelby County Groundwater Control Board.

Protect Our Aquifier has a governing board of 10 and, perhaps more important, has an informal membership core of 1,800, communicating full-time via Facebook and fully able, as circumstances have demonstrated more than once, to mount an organized public presence. — Jackson Baker

The Leftist Comedy Show

It was the one-year anniversary of the Leftist Comedy Show, and show host Stan Polson thought he had one more joke — but, just to be sure, he checked an index card tucked in his breast pocket. “I’m really good at this,” he mumbled. “Oh yeah, yeah,” he said, reading deadpan from the card: “Men and women are really different. [laughter] Like, if you look on the internet, you can really see a lot of that. [laughter] Women are like, ‘Quit harassing me!’ And men are like, ‘Nobody’s harassing you, whore! Shut up! Kill yourself!’ [pause] That seems different.”

Resistance can be funny. At least, that’s the take of those involved with the Leftist Comedy Show. It was born in the backyard of the Lamplighter Lounge and was supposed to be a one-off event, created by a group of friends with similar political interests. Turned out, the idea had legs, and the crowds are getting bigger.

The first events were planned with the goal of creating “safe space” comedy for audiences who might not feel comfortable at regular shows and open mics.

“A lot of people think we get offended by offensive material,” he says. “But that’s not really the case so much as we believe people when they tell us why they don’t come to comedy shows. At a leftist show, you’re not going to hear any rape jokes. You’re not going to hear any racial slurs. We heard women didn’t feel safe at open mics, comedy in Memphis was too segregated, and a lot of our transgender friends wouldn’t go because they’d hear jokes that made them uncomfortable.” The result is a comedy showcase with a lot of familiar faces on stage, but a unique audience.

The next Leftist Show is slated for April 15th at Midtown Crossing. It will be hosted by the Living Room Leftists, a local pro-union folk band. — Chris Davis

Mid-South Peace and Justice Center

“It’s all about poverty at the end of the day,” says Brad Watkins, executive director of the Mid-South Peace & Justice Center (MPJC). “Our organization was founded on the birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. because our founders believed, as Memphians, we have a special responsibility, as this was the city in which King was murdered. [They wanted to build] on the work of Dorothy Day, of Chavez, of King. This organization stands to push that vision forward.”

MPJC launched in 1982 and originally had a wide-ranging, four-pronged mission: opposing apartheid; targeting industrial polluters; calling for nuclear disarmament; and opposing U.S. military involvement in Central America. Some 20 years later, the focus was narrowed to local issues when Jacob Flowers, whose parents were active at the center in the 1980s, became executive director. The center has now become a mother ship, of sorts, for other fledgling organizations, including the Memphis Bus Riders Union, Memphis United, and H.O.P.E. (Homeless Organizing for Power & Equality).

Watkins became executive director in 2014. “If you look at homelessness,” he says, “if you look at public transit, if you look at our work with low-income tenants or immigrants or criminal-justice reform — all of that has its roots in poverty. And not just poverty like it’s just something that happens, like the weather.

“Low income people pay all the late fees; they pay all the reactivation fees,” Watkins continues. “The system bleeds people dry and keeps them trapped in poverty. If you wanted to sum up all of the issues we work on, it comes from a place of liberation from oppression, and poverty is the means to oppression.”

Watkins says the center’s role in the current spate of activism is a supportive one. He says activism works best when a movement is led by the people most affected by an issue.

“Here’s what I want to say,” says Watkins. “It’s never too late for someone to get involved. None of us were here at the beginning of the movement, and none of us are too late to be a part of it.” — Susan Ellis

Activist Grassroots Groups in Memphis (partial list):

M.A.R.C.H. (Memphis Advocates for Radical Childcare)

Fight for $15

Healthy and Free Tennessee

Memphis Bus Riders Union

Memphis Feminist Collective

Comunidades Unidas en Una Voz

Home Health Care Workers

Memphis Voices for Palestine

Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ)

Official Memphis Chapter of Black Lives Matter

Sister Reach

Save the Greensward

OurRevolution 901

Preserve Our Aquifer

Mid-South Peace & Justice Center

Basheeradesigns | Dreamstime.com

Basheeradesigns | Dreamstime.com  Joey Miller

Joey Miller  Micaela Watts

Micaela Watts

Chris Shaw

Chris Shaw