Jeanne Seagle’s favorite Bible verse begins, “He leadeth me beside still waters and he restoreth my soul.”

“I’m not religious; don’t get me wrong,” Seagle says. “But I had to learn my Bible verses as a kid. And I remember them. I really like that one.”

Her own still waters are found at Dacus Lake, the subject of “Beside Still Waters,” Seagle’s first one-person art show at L Ross Gallery.

Fletcher Golden

Fletcher Golden

‘Jeanne In Fog’

“My subject matter is the land inside the levee right across the Mississippi River from Downtown. Dacus Lake,” she says. “I have a great affinity for that land. I’ve always loved to go across the river, from the time when I first moved to Memphis. It was so much fun to go ride around in the fields and go down to the sandbars. I go over there a lot. It’s just a great getaway from Midtown Memphis. I can drive over the bridge and be over in the wilderness in 20 minutes.”

Seagle’s show includes 11 large black-and-white drawings and 11 watercolors of the Dacus Lake area. She takes photographs, which she uses for her drawings. “They’re very precise. Very photo-realistic drawings. It takes me about a month to do each one.”

Jeanne Seagle

Jeanne Seagle

of Humor,’ News of the Weird illustration for the ‘Memphis Flyer’

During her art career, Seagle, 72, has worked as an illustrator for ad agencies and publications, including the Memphis Flyer, where her cartoons illustrated News of the Weird for many years. Her public art can be seen at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital, and Methodist University Hospital. Books that feature her illustrations include Mickey and the Golem by Steve Stern and Mommy Without Hair by Selene Benitone.

But Dacus Lake has flowed through her artwork for decades.

In the mid-1990s, before they were married, Seagle and Fletcher Golden spent a lot of time at Dacus Lake, where Golden lived for a while in a mobile home. “I’d just go over every Friday night and ride through the bean fields. I really got to know the land over there. I house-sat for him, and I would just go down to the river and paint and draw.”

The area was a new world for Seagle, who was born in Pueblo, Colorado. “All of my art was about going out to Colorado to visit my family,” she says. “I just did brightly colored paintings of mountains and canyons and mesas and that kind of thing. I’d go out there every year and ride around and paint.”

When her elderly relatives died and she stopped making the trip to Colorado, Seagle was at a loss for subject matter. “I was not all that crazy about the flat Delta land. But little by little I started seeing all the subtle beauty and the surprises you find when you get up close in the swampland and the waterways. And I started making pictures of this Delta land.”

It never stays the same, she says. “It floods every year. It’s inside the levee, and that makes the landscape change. The waters rise and recede. It’s a great place for all kinds of water birds and animals to live. And because it floods every year, it’s not developed. It keeps the humans away. Because of that, there are animals that just roam up and down the Mississippi for hundreds and hundreds of miles.

“If you go early in the morning, you see these animals. I saw a panther one time when I got up early and was sitting quietly doing some watercolor painting.”

And then there are the trees. “Because it floods, the roads are elevated so that trees grow up around them, but the trees take on very strange shapes, too, because of the Delta tornadoes that come through and tear off the limbs of the trees. They’re all raggedy-looking trees that are so unusual.”

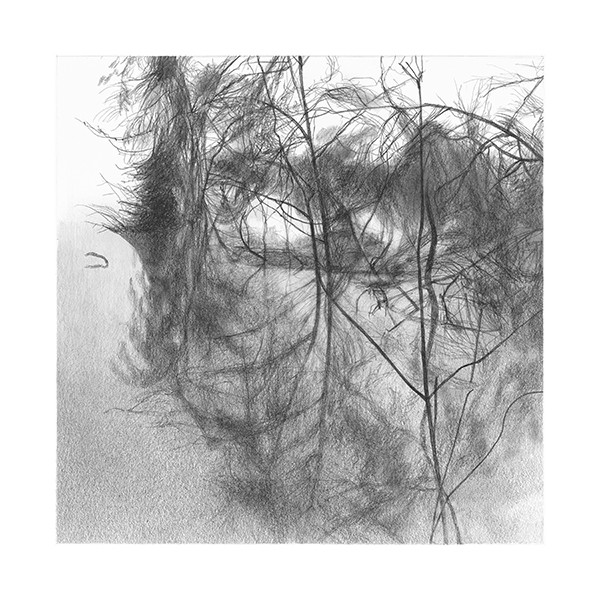

Jeanne Seagle

Jeanne Seagle

charcoal pencil on paper

The area does attract some eccentric people, Seagle says. “When Fletcher lived there and I was visiting on a regular basis, there was a bait shop on stilts. It was kind of a community gathering place.”

And, she says, “There were other people living over there at the fish camp — people who don’t like living in civilization. They were people who are close to the land, people who hunt for beaver tails. Just very earthy, country people who have known all about the country, and the last thing they want to do is live in civilization. We got to know them, and that was really interesting.”

Seagle’s love of nature began when she was a child. Her family moved from Colorado to Mississippi when she was very young, then they moved to the woods of Arkansas when she was five. “My father worked for the department of forestry, and he got a job as a forest ranger in Western Arkansas in the Ouachita Mountains. As a little child, I was living in this forest. An only child.”

Seagle spent time drawing and walking through the woods by herself. “Being all alone with no brothers and sisters out in the country was probably a big influence,” she says. “If I’d been living in town and had lots of people to play with, I might not have become an artist.”

She was known for her art ability in school. “I remember in the first grade I would draw tattoos on little boys and I’d draw paper dolls for the little girls. I charged a dime. I kept on doing that all through school. I was the class artist.”

In high school, Seagle took an art class trip to Memphis Academy of Art, which later became Memphis College of Art. “I saw these kids in there that were beatniks. I loved that. I really wanted to be a beatnik. So when I got old enough to go to college, I came up here.”

She moved to Memphis in 1967. “By this time, the Art Academy had all the great people: Ted Rust, Bill Womack, John Mcintire, Burton Callicott, Ted Faiers, Veda Reed, Bill Roberson. Murray Riss started teaching when I was there. It was just wonderful to be around these people, and I got to take classes from all of them.”

Seagle majored in illustration. “When I was a little girl, I loved looking at my mother’s magazines. I really was not exposed to art galleries. We lived in the forest ranger station in Western Arkansas, so the art that I saw was in my mother’s magazines. And I wanted to be a magazine illustrator, a children’s book illustrator.”

Her schooling was interrupted after she married her first husband, a medical student. “My first marriage was very brief — to somebody that I met here in Memphis, and we moved to Los Angeles.” That was “a different lifetime,” Seagle says. “He was gone most of the time, being an intern at the hospital.”

Jeanne Seagle

Jeanne Seagle

Jeanne Seagle and Pomegrante Studio

After her divorce, Seagle returned to Memphis, where she completed her degree at the Art Academy.

She took a job as assistant executive designer with Dobbs Houses. “I dressed like the young executives. I wanted to be a young executive. I worked at Dobbs Houses in the interior design department and went to work in a high-rise building and dressed up with hose and skirts.”

Then, she says, “The director of my department was found to be embezzling from the company and the whole department was fired. That’s when I changed. I was fired from the executive track and so I just kind of totally changed then and relaxed and became more of a Bohemian, I guess.”

In 1973, Seagle got a job working with a couple of her classmates, Ellis Chappell and Jim Williams, at The Grafe, the in-house graphics agency for Stax Records. They created and produced Stax album covers.

When The Grafe downsized, Seagle became a founder of Chappell, Williams and Seagle, an illustration studio in the Timpani Building, an old cotton warehouse. The Malmo & Associates ad agency was their biggest client. After five years, they sold the building.

“We made a bunch of money,” Seagle says. “So I just went to Europe, traveled around, went to all the art museums. I came back and I started doing fine art.”

When her money ran out, she went to work for Malmo & Associates.

In 1993, Seagle became a freelancer. A major client was Contemporary Media, Inc., where she became a regular illustrator for the Memphis Flyer. She illustrated the Flyer‘s News of the Weird column for 20 years. “That was great training for what I’m doing now,” she says, “which is obsessive black-and-white drawings.”

Her Flyer illustrations were composed of “little tiny dots,” she says. “You had to be obsessive-compulsive to do it. And that’s exactly what I’m doing now in my landscape drawings. I’m just doing these tiny little marks that take forever to do. Everybody looks at them and says, ‘Oh, my God. You just have such patience to do that.'”

Seagle also began doing public art, landing UrbanArt Commission grants to create mosaic murals on two trolley stops on Madison.

In 2012, she created the 16-foot sculpture, I Can Fly, at Le Bonheur: “It’s a giant obelisk with mosaics on all four sides depicting the seasons with children playing, climbing trees. On top is a giant bluebird about the size of a Volkswagen Beetle with a little kid riding on top of it.”

The next year, she created the 16-foot-tall Genome Kids sculpture at St. Jude. She describes it as “a giant DNA helix with whimsical-looking little children climbing it.”

She then did a series of 6-foot square paintings, including “giant painted quilts,” at Methodist.

“I made a lot of money,” she says, “and I was able to, pretty much, retire from commercial art work and turn to fine art.”

She began booking shows, beginning with a one-person show at the Delta Cultural Center in Helena. Then, she says, “Linda Ross called me up and asked me to be in one of her shows. That was really a great turning point in my fine art career, to be able to be in a well-respected gallery. I’ve been in shows with her for five or six years.”

Ross, now retired from the gallery, says, “What has always attracted me to an artist is the movement, the feeling, of the line work in their art. So it’s no wonder that I found Jeanne’s body of work so compelling. She has such a deft hand, whether it’s the broader brush strokes in her quietly moving watercolors or the delicate-layered markings in her stunning penciled landscapes. Simply masterful.”

Jeanne Seagle

Jeanne Seagle

‘Flooded Shoreline,’ charcoal pencil on paper

Seagle’s current show at L Ross Gallery was supposed to open in the spring but was pushed back because of the pandemic. Originally, Seagle thought the “the fog, the water, and these stark winter trees” would be “too depressing” for a spring show. “Then, as it turned out, with the pandemic, I don’t think pretty pastel-colored pictures of things would be very appropriate for our world right now. These mysterious, dark pictures are very appropriate.”

“The level of detail and technical skill in these pieces speak for themselves,” says L Ross Gallery owner Laurie Brown. “But, to my mind, what really sets Jeanne’s work apart is her ability to capture the quiet, ephemeral moments of life so exquisitely. You can almost hear the breeze whispering through the branches or feel the cool dampness of the fog.”

As for future plans, Seagle says, “I want to make bigger pictures, and I really want to start being in museums.”

Seagle and Golden, who have been married almost 20 years, live on an acre of land in Cooper-Young. “It’s made the pandemic much more bearable to have all this land, all these trees in our backyard. It really looks like we are living out in the country.”

Seagle still makes the trip to Dacus Lake. “I’m still totally fascinated with this landscape. It’s always changing. The water conditions are always changing. The floods and the water rising, morning and night, and the light — it’s just full of ever-changing subject matter that thrills me.”

“Beside Still Waters” is on view through September 5th at L Ross Gallery.