Its full name is First Congregational United Church of Christ, but nobody in Memphis ever calls it that. “First Congo” isn’t the city’s oldest church or its largest. It doesn’t boast the fanciest architecture or the wealthiest congregation. But between its nascent solar energy plan, its many social justice programs, and its fruitful partnerships with so many local artists, it aims to be the city’s most visibly progressive community of faith.

“We’ll never be a megachurch,” says Reverend Cheryl Cornish, who has seen weekly church attendance grow considerably since she was installed as pastor in 1988. “We’re too far outside the mainstream, and we always have been,” she says.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Considering that controversies associated with gay marriage continue to dominate news cycles and that First Congo began to create an “open and affirming” environment for gay, lesbian, and transgender Christians in 1991, she’s probably not wrong on that account. “What we can do, however,” she adds, “is to be here for all those other people who want the things Christianity has to offer but who want it without all the bigotry.”

First Congo has a lot of history in Memphis, and it had a lot of things to celebrate in 2013. In October, the church, which was founded to serve Union soldiers following the battle of Memphis, celebrated its 150th birthday. Cornish, who joined the Memphis church when weekly attendance hovered near 25, also celebrated her 25th year as pastor. And although her leadership hasn’t seen First Congo grow into a mega-church, you only have to visit the Cooper-Young Farmers market, drop in on a symphony performance in the sanctuary, watch a documentary produced by True Story Pictures, or catch an improv show by Playback Memphis to understand that First Congo’s footprint is larger than it might initially seem. The church’s impact on Memphis culture, particularly in Midtown, is considerably deeper than active membership rolls might suggest.

In the past decade, First Congo has become home to a long roster of independent artists, actors, farmers, filmmakers, midwives, dancers, crusaders, union leaders and, yes, even bicycle and unicycle enthusiasts. The church also houses a hostel that hosts up to 6,000 international visitors annually. It shares its abundant space with a daycare center, a recycling center, a fair-trade store, a fencing instructor, a couple of vegan cooks, a volunteer bicycle shop, and at least 20 twelve-step groups.

“We believe in recovery,” says Julia Hicks, First Congo’s director of missions. Hicks says she’s never sure how many shared-space partners the church has at a given time. “But the number hovers around 30,” she says.

“What’s special is how much emphasis the church places on the arts and how much they really want to have us there,” says Voices of the South managing director Steve Swift. Swift is probably best known to area theater fans for his popular Sister Myotis character, an over-the-top drag parody of the modern conservative Christian that has somehow developed a fanbase even among conservative Christians. “You really feel supported here,” Swift says.

Voices of the South, a small but prolific confederation of theater professionals dedicated to the production of original, regionally relevant theater for children and adults, started using First Congo as an alternative performance space in 2005.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

“But we never dreamed of having our own permanent brick and mortar theater,” Swift says. “In fact we kind of reveled in our freedom to perform wherever we wanted to perform. And then the folks at First Congo came to us and asked if we’d be interested in having our own theater space.”

With the help of two enhancement grants from ArtsMemphis and a grant for moveable seating from the Jeniam Foundation, Voices quickly transformed the cramped southwest corner of First Congo into TheatreSouth, a versatile and viable small performance space.

“We called it TheatreSouth because we initially thought we’d probably be renting the space out a lot,” Swift says. “But we may change the name, because we haven’t really had much time for anything but Voices of the South shows.”

“Voices has become such a major theater in this city,” Hicks says, praising Swift’s wicked, church-inspired comedy — and darker and more difficult work by storyteller Elaine Blanchard, who compiles the true stories of prisoners, especially female prisoners, and shares them, with the aid of area actors, directors, and musicians. “It’s such a mutually beneficial relationship,” Hicks says. “Even if the work isn’t religious, the theater is so committed to this community, and it is very spiritual.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

In 2000, when Cornish convinced an active membership of less than 200 souls to purchase and renovate the former Temple Baptist Church, a dilapidated 83,000 square-foot building in Midtown’s Cooper-Young neighborhood, she allowed that they were probably buying more church than the congregation could use. She sold the super-sized venture by comparing the risky undertaking to Noah’s Ark, which had to be big enough to accommodate creatures great and small.

Cornish’s Noah metaphor has taken a literal turn with the church’s new “Blessed Bee” ministry, a program to care for 100,000 honey bees during a time of widespread colony collapse and build a cottage industry based on honey production.

“Cheryl emphasized social justice, and that was always very attractive to me,” says associate pastor, Reverend Sonia Louden Walker, who joined First Congo’s ministerial staff in September 2008, after raising three children and having successful careers in broadcast journalism and the not-for-profit sector. “That was like the Jesus I always knew,” she says. “I came from the AME [African Methodist Episcopal] church and so my God was always bigger than our individual concepts of race and class.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

that reflects First Congo’s identity and responds to regular features on the church’s calendar.

Walker, who began her studies at the Memphis Theological Seminary at a time in life when most people would be looking forward to retirement, used connections she’d made while working in television to grow the church’s food ministries. She deepened First Congo’s relationship with the Memphis Food Bank and cultivated relationships with other area food distributors who have asked to remain anonymous. As the economy slipped into recession, charitable efforts aimed at addressing food insecurity grew so fast that in 2011 Molly Peacher-Ryan was hired as the church’s full time minister of food justice.

“In most work, growth is a good thing,” says Peacher-Ryan who takes care of the church’s community garden and runs the Blessed Bee program, as well as the church’s food pantry and its Food for Families ministry.

“But here, growth means things aren’t going very well. Memphis is one of the most food-insecure cities in America. And while we may love this work, none of us like the fact that we have to do this work.”

Cornish, who was president of her graduating class at Yale Divinity School, likes to remind her congregation that it was once called “The Strangers church,” so named because at the end of the 19th century, it was located in a bustling hotel district on Union Avenue near Third. She has made this curious piece of church history a part of her personal philosophy for church development. “Our job isn’t to determine who belongs in the church and who doesn’t,” she says. “Our job is to welcome the people God sends us.”

Cornish laments that she and her church have been excluded from some church and clergy circles since First Congo became an open and affirming church with strong female leadership.

“There are times I’ve thought, to do what’s right we might just have to go it alone,” she says. “And maybe that’s our mission. Historically, it fits being a church of strangers.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Worshipers at a First Congo service

It’s not clear whether Cornish and company, having meshed so closely with their community while growing their own creative neighborhood, have ever been in danger of being alone.

The pastor’s office at First Congo isn’t a very private space. You can look through a window and see directly into the dance room where, depending on the time of day, you might catch belly dancers working their abdominals or observe New York transplant Joe Murphy as he leads a group of children in a theatrical, world-music-inspired, sing-along experience called Music for Aardvarks.

Cornish says she’s inspired watching Murphy, a shared-space partner, who, in turn says he doesn’t know where Music for Aardvarks would be if it wasn’t for First Congo’s commitment to area artists.

When Murphy and his wife, Virginia, moved from New York to Memphis to raise their family, they went directly to First Congo, looking for a space to instruct, rehearse, and perform.

“It was so supportive,” Murphy says. “At First Congo, they really want people to be included. They try to open doors for everyone in inclusive ways. I want our programs to enhance that idea.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Murphy also works with his wife in the First Congo-based improv group, Playback Memphis, a company that makes the kind of art that enhances Cornish’s idea of a strangers’ church. Playback is an experimental theater troupe that explores relationships, the idea of community, and the boundaries between social justice and performance.

“Right now we’re working on a huge project with the Mid-South Peace & Justice Center,” Murphy says. “It’s called the Police/Community Reconciliation Project. We go into a community like Frayser and gather experiences and, working with the police, we ‘play it back’ to them to identify barriers that might exist.”

When First Congo celebrated its recent birthday, the congregation participated in a call-and-response litany acknowledging that some churches are better known for who they exclude than who they include. The collective answer to that charge: “We’re not all like that.” But nobody had to say a word to know the score, all you had to do was look around the sanctuary.

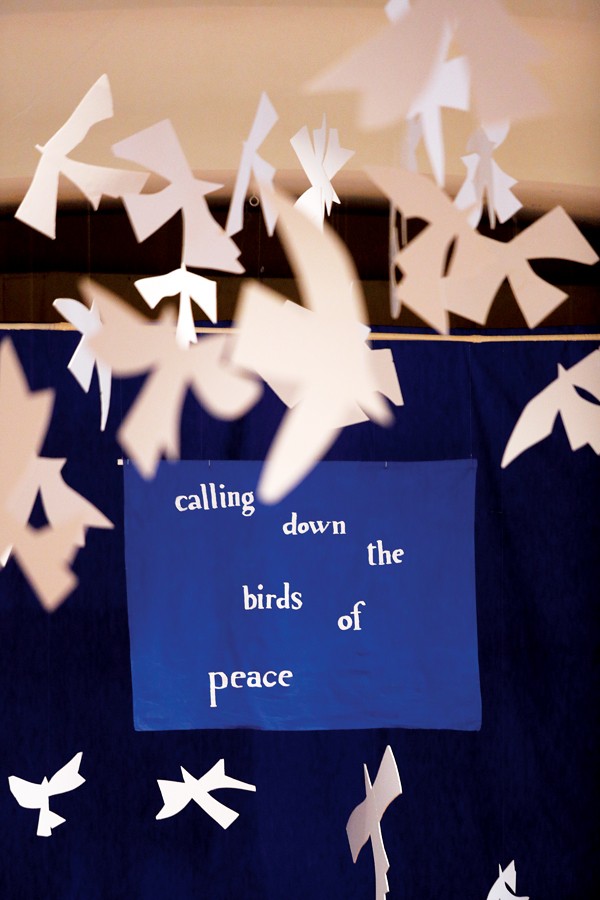

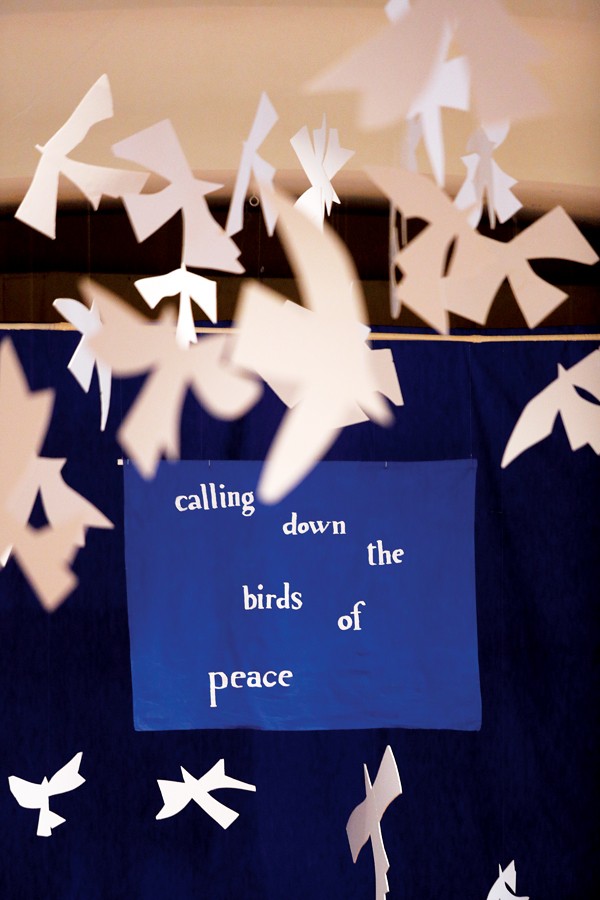

Mary Button is First Congo’s minister of visual art. She’s a New York University grad who grew up Lutheran. She made art about religion, until she trained at divinity school to develop her skills as a liturgical artist. Button is tasked with turning the First Congo sanctuary into an ever-changing series of massive art installations that reflect the congregation’s identity and respond to regular features on the church calendar. Button likes to talk about the transformative powers of art, and an idea she calls, “sacred time,” the condition she hopes her installations promote.

“It is central to First Congo’s vision to imagine God in a new way,” Button says. “That means imagining the Creator in our lives in a new way. And it means seeing ourselves in a new way in the world. These are some things that art allows us to do.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks