Last summer, New York art critic Christian Viveros-Fauné wrote in The Village Voice that folk art is merely the new fad in big-business art collecting and that folk artists have “precious little to say about our time’s most pressing issues.” Folk artists, wrote Viveros-Fauné are “Sunday painters, stitching septuagenarians, and religious cranks” who are usually “dead, mentally impaired, or can barely speak for themselves.”

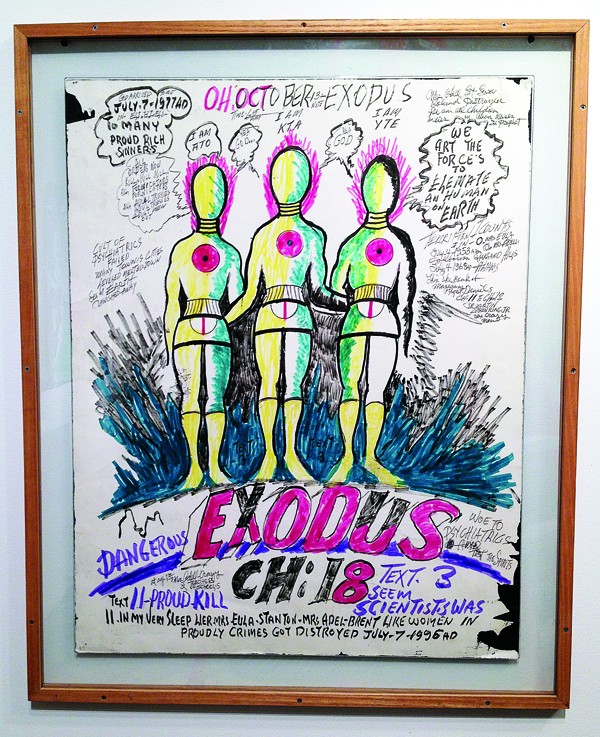

Royal Robertson’s art piece in “Akin”

Viveros-Fauné’s so-called Sunday painters would probably include reclusive spiritualist Royal Robertson, a New Orleans-based artist who used tempera paint on wood or posterboard to make work about the end of days, as well as Memphian Joe Light, a self-taught painter and driftwood sculptor. Work by Robertson and Light and eight other folk artists is currently on display at Crosstown Arts Gallery as part of the show “Akin,” through July 6th.

“Akin,” curated by Southfork gallerist Lauren Kennedy, is meant as a companion show to the Brooks’ upcoming “Marisol: Sculptures and Works on Paper” exhibition. The works all come by way of the Webb Gallery in Waxahachie, Texas. The Web Gallery, according to its website, is interested in “painted or repaired objects, fraternal lodge items, carnival banners, tramp art, memory jugs, quilts, and just killer oddball stuff.”

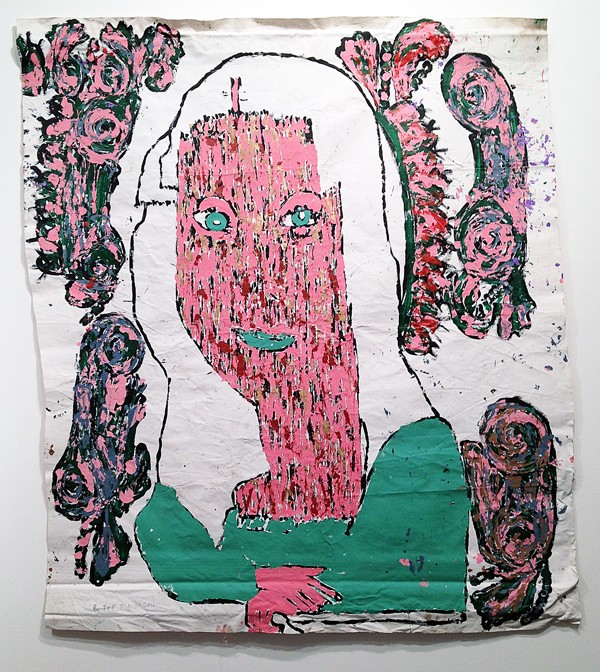

Ike Morgan’s Mona Lisa

Like the work of the genre-bending sculptor Marisol, who often used a folkish style (despite her formal training), the works in “Akin” have range. There are oblique hubcap sculptures by Hawkins Bolden alongside Ike E. Morgan’s grotesque canvas paintings of George Washington. Kennedy says, “Looking at Marisol’s work, there was a quality that struck me the way folk art does. The materials and the way you can see her hand in the work … the work felt akin to a lot of folk and outsider art that I enjoy.”

“Folk art” is a loose category. Though it usually describes work by untrained or informally trained artists, it has also come to describe a style, the hallmarks of which are cheap or found materials, obsessive mark-making, and a disregard for formal perspective. Painters like Esther Pearl Watson, whose landscapes are featured in the show and often include sparkly UFOs and scrawled writing, are more D.I.Y than traditionally folk. The same is true of Fred Stonehouse, a featured surrealist painter who holds a B.F.A. from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Stonehouse and Watson aren’t exactly outsider artists, but their work is in the folk canon, alongside Robertson’s rough drawings and Light’s Old Testament-inspired sculpture and painting.

Watson’s paintings, particularly, unify “Akin.” Her 2012 painting Bail Bonds shows a small female figure walking in front of a storefront. Yellow balloons float to the sky, and a UFO hovers unobtrusively over a leafless tree. It is a barren scene in what looks like a warm, Texas winter. A notation at the top of the painting reads, “Dad is in Jail in Florida. He gets released the 29th. Mom is upset. He doesn’t know if he wants to come back or not.” There is something flexible and self-conscious about Bail Bonds. It is accessible like a comic but has the depth of a much-worked-over painting; perhaps Watson gave the work a folkish look to create this effect.

“Akin” does well by the “religious cranks” that Viveros-Fauné maligned. The critic’s wording is reactionary and rude, but he touches on something true: Folk artists could usually give a flip about big art world business, and so folk art has always been a weird bedfellow with the gallery scene. What is called for is more shows like “Akin” that embrace a broad and warm aspect of an important community of artists.