If you drive through Midtown, there are no shortages of places to find fresh food. In fact, there are three full-scale grocery stores within a one-mile radius of each other. But, as you venture further south, along Bellevue into South Memphis, you won’t find many grocery stores. Instead, you’ll see streets lined with fast food joints, dollar stores, and corner stores selling junk food, beer, cigarettes, and a few overpriced groceries such as white bread and milk.

Marlon Foster, longtime resident of South Memphis and pastor of Christ Quest Community Church near McLemore and Mississippi Boulevard, says accessing healthy, non-processed food is a huge struggle among his neighbors. People “literally right next door to me don’t have real food to eat. There are a lot of people who walk up and down the street to get food from me and other neighbors,” Foster says. “We see it all the time”

Since the church opened 14 years ago, Foster says he’s been offering Sunday-morning breakfast to his congregation. Half come just for the guaranteed meal, he says.

“It’s about gathering, but it’s also a direct confrontation of hunger,” Foster says. “People are not coming to socialize; they’re coming because they’re hungry and need something to eat.”

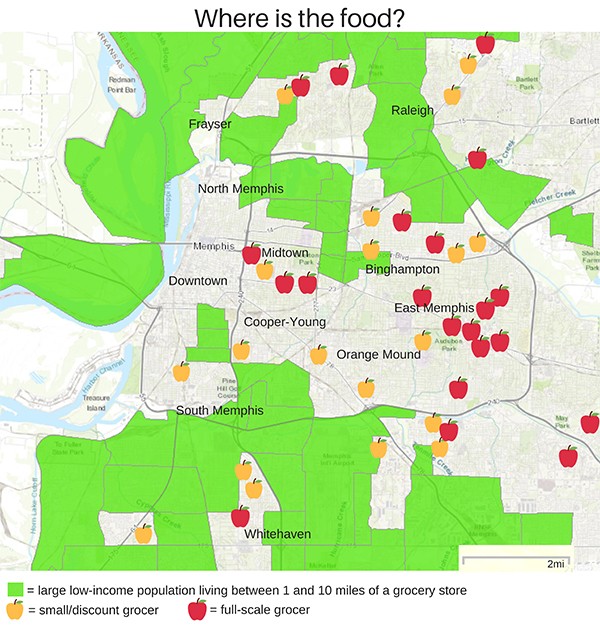

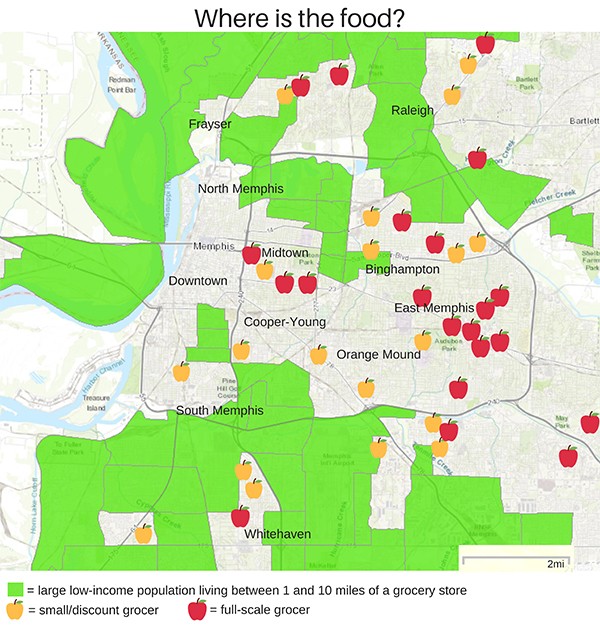

Source: USDA; modified for the story

Source: USDA; modified for the story

The green fields in the above map indicate food deserts.

South Memphis isn’t the only Memphis neighborhood where residents don’t have reliable access to fresh, healthy food. In fact, on the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s atlas that highlights areas in the U.S. with low access to food, much of the city of Memphis is colored green. In this case, green isn’t good. Green means that the people living in that census tract are low-income and live between one and 10 miles from a grocery store.

Click a button on the interactive site, and magenta begins to overlap with green, showing the areas in Memphis where a large portion of households don’t own cars. Green plus magenta equals food desert, which the USDA defines as a community where at least 500 people and/or 33 percent of the population reside more than one mile from a grocery store and do not own an automobile. These areas exist heavily here in Whitehaven, Orange Mound, South Memphis, and North Memphis.

The latest report by Feeding America, a national hunger-relief organization, shows that 198,610 Shelby County residents were food insecure in 2015, meaning about 21 percent of the population faced “lack of access, at times, to enough food for an active, healthy life for all household members and limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate foods.”

These are communities where residents do not live in close proximity to affordable and healthy food retailers, especially those that sell fresh fruits and vegetables. Healthy food options in these communities are either hard to find or unaffordable. Residents can, however, easily access processed food with little or no nutritional benefit and that is high in fat, sugar, and sodium.

The USDA cites that in most cities, food deserts are found in low-income areas and neighborhoods of color. Memphis, a city that is about 62 percent African American, is no different. On the USDA’s food desert atlas, green largely covers the city’s poorest zip codes — 38126, 38105, 38108, and 38106, which have an average median household income of $19,107 a year. In these neighborhoods, families struggle to find and afford healthy food, children rely on school-provided meals, and parents have to make trade-offs between basic needs and adequate food.

Closed Doors

When Kroger closed two of its stores in South Memphis and Orange Mound in February, the residents who depended on those stores were suddenly struck with the reality of not having a place to buy food.

Rhonnie Brewer, chief visionary officer of local consulting firm Socially Twisted, says she doesn’t live in either of those neighborhoods, but when she heard about the predicament of the residents there, she was compelled to help “meet the need.”

After attending neighborhood meetings, while researching and contacting potential grocers to fill the space, Brewer says she realized she needed hard numbers to actually prove a grocery store could be viable in those locations. So, Brewer went to the Memphis City Council, asking for funds to conduct a grocery store feasibility study. Though some of the council members were “strongly for it,” she says, others “weren’t concerned” and couldn’t understand why a study was necessary.

“It wasn’t easy,” but after what Brewer says was “lots of presentations and lots of begging,” the council voted to fund the study.

Still, some council members said they didn’t see a need for the study. “I was dismayed,” she says. “Because anything that impacts the community’s citizens is the responsibility of the city ultimately.”

The study, based on census data, traffic counts, and other numbers, showed the need for a grocery store in the two spots, but in locations like South Memphis and Orange Mound, Brewer says the study also suggested a traditional grocery wouldn’t work. Because profit margins for the two locations were projected to be low or negative, Brewer says the grocer would need to be “creative about making money … . It’s completely doable, it requires thinking outside of the norm for grocery stores.”

Brewer then returned to the city council to propose the creation of a grocery store prototype that would be most viable in low-income areas. Creating the prototype would have cost the city about $174,000, but the council told Brewer it wasn’t in the budget. “They just didn’t go for it,” she says, and some of the council members “basically avoided me. I sent emails, called, texted, left voicemails, called their assistants, and still got no responses from some,” Brewer says. “It left me at a loss.”

Theo Davies at Green Leaf Learning Farm.

Steps Forward

Brewer’s talks with the city council were not in vain, though. Last week, the council took a step toward bringing grocery stores into the city’s food deserts, but in a different direction. The council voted to allocate $360,000 from surplus funds to an initiative meant to make it easier for grocers to open shop in underserved, low-income neighborhoods.

The Healthy Food Financing Initiative (HFFI), modeled after the USDA’s national program, is designed to expand access to nutritious food in communities by developing and equipping grocers, small retailers, corner stores, and farmers markets that sell healthy food.

Through the initiative, healthy food projects in Memphis’ USDA-certified food deserts will be incentivized with loans and other assistance to offset the costs of land/facility purchase, construction/renovation, and business start-up/operations. The initiative is spearheaded by The Works, Inc. CDC, a housing and community development group that aims to rebuild and restore South Memphis.

Roshun Austin, president and CEO of The Works says the initiative will be “vital” in eliminating food deserts in neighborhoods where she works in South Memphis, and in others, such as North Memphis, where there are “whole blocks of neighborhoods that barely have convenience stores.”

“We’re not in it just to provide a loan,” Austin says. “It’s about what we can provide and what it means for families’ health. This is a way to focus on how we reduce our health disparities.”

Ma Ani Community Service Summer Program campers.

Austin is wasting no time getting started, either. She’s been working with Rick James, owner of the local Cash Saver chain, to bring a grocery store back to Kroger’s old location in South Memphis’ Southgate Center.

James, who has already signed a lease with the property owners for the 31,000-foot space, says “it’s a done deal” and expects the store to open sometime in August. James has been operating stores in Memphis for about 30 years, and says he’s “confident” that the store will be successful.

“The neighborhood is very, very similar to the ones where we already have stores,” James says. “We know how to provide for these customers, and we’re comfortable in the community. I wouldn’t be doing it if we didn’t think it could be successful.”

Whether the store is a success or not, James says Cash Saver is “not in it for the short-run,” citing a $1 million front-end investment for store renovations.

Unlike other grocery stores, Cash Saver has a “price plus 10” format. This means at the register, customers pay the price listed on the shelf, plus tax, plus an additional 10 percent of each product’s cost. James says this allows the store to offer the lowest price for all products, instead of just for a few on-sale items. Despite the extra 10 percent, James says he’s “pretty certain” that Cash Saver’s products are cheaper than those found in other grocery stores.

With Cash Saver set to open at the end of the summer, hope is on the horizon for the approximate 55,000 individuals living within a 3-mile radius of the shopping center. Still, in a zip code where the annual average household income is a little over $29,000, transportation options are limited and obstacles still stand in the way of getting to the store. And those without access to a car, living further than a mile from the store, by USDA definitions still reside in a food desert.

Maricela Lou-Gator welcomes Ma Ani counselor Deen Bowden and campers.

An Oasis

Opening grocery stores is one way to address the food desert epidemic in Memphis, but tucked away in South Memphis another type of solution — and an oasis — already exists. Sitting to the south of Walker, near Mississippi Boulevard, a two-third-acre learning farm spans over 30 formerly vacant, blighted lots and three abandoned buildings.

The Green Leaf Learning Farm is a USDA-organic-certified farm, where everything from jalapeños and thai chilies, to zucchini and tomatoes, to sage and thyme is grown. The food is sold at the farm, as well as the South Memphis and Cooper-Young Farmers Markets. Residents of the neighborhood receive a slightly reduced rate on food, and every week, food is given away to neighbors.

Marlon Foster is not only the pastor of Christ Quest Church, but he’s also the founder of Green Leaf and the organization that operates it: Knowledge Quest. Foster grew up just a few blocks from where the farm sits now and says he’s seen the population and economics of the neighborhood shift over the years. People moved out, businesses closed, buildings became dilapidated, and lots turned to blight, he says.

“It’s challenging for me to ride down the same streets I rode down as a kid with my parents now and remember what used to be,” Foster says, citing the number of grocery stores that used to be in the community. “We had what we needed in the neighborhood, but now a lot of it is gone. We are having to literally build from the ground up with community gardening to try to fill the gap for that loss.”

Green Leaf is an effort to be a “direct redress” to the food desert in which it operates, Foster says. “At least with the presence of Green Leaf, those food desert realities begin to diminish for those in a close proximity to the farm,” Foster says. “Through us, families do have access to healthy produce — and soon to be — eggs and honey.”

Because the goal of the farm’s parent organization, Knowledge Quest, is to provide high quality service to “one of the most under-resourced and underserved neighborhoods that traditionally would not get that,” Foster says, Green Leaf strives to grow the highest quality food.

“We don’t just provide vegetables; we’re committed to growing the healthiest of the healthiest,” Foster says. “We’re passionate about vegetables with high amounts of nutrients, like leafy greens — hence our name, Green Leaf.”

Green Leaf has three focuses: community and economic development, food access, and education. Student education, through “mass exposure” and “intentional engagement” to growing food, is the most important, Foster says.

Students at Knowledge Quest have the opportunity to learn about the different aspects of urban agriculture, and those who show interest are given the opportunity to join a club and learn more in hands-on ways. The club members learn everything from water and soil conservation to how to project harvest yields, Foster says.

“So if they want to be outside and get their hands dirty or own a farm or go into an agribusiness career one day, they’ll have that experience to do that,” Foster says. “Our goal is for a child to have the chance to experience all the elements of the food cycle.”

Urban farming is one way to curb the food desert problem, but Foster says it’s not the single solution. “I am still an advocate that it should not be that for under-resourced communities to have healthy food, they have to grow it themselves,” Foster says. “I wouldn’t want to go down that road too far — to say that it’s the whole answer.”

Foster says community farming is a good way for people to become empowered and immediately respond to challenges in their neighborhood. “But still, we want access to produce in traditional outlets,” Foster said. “I want a high-quality grocery store in proximity to me in South Memphis, where I live.”

It all works hand-in-hand, Foster says, as urban farming can be one piece of a broader solution.

More Than Food

Despite some forward strides, there are still a number of neighborhoods in Memphis where residents are without healthy food options. Rhonnie Brewer says it’s important to keep the conversation about food deserts going.

“The minute it gets quiet and it’s no longer relevant, it gets swept under the rug,” Brewer says. “Then it becomes the status quo, and it’s normal old news. At the end of the day, if you were to look at the USDA food desert atlas, you see Memphis covered in all these spots that are food deserts, and that’s an issue that has to be addressed. I just don’t want these individuals who are now living in these situations to get forgotten about.”

People often don’t understand the obstacles that stand in the way of certain demographic groups in some neighborhoods accessing fresh food, Brewer says.

“If you are a senior who lives in Orange Mound off of Park with no means of transportation, imagine the hurdles you would have to go over to get to the closest full-scale grocery.”

Grocery stores do more than just provide food, Brewer says. They often serve as anchors in communities. Where there is a grocery store, there is a centralized hub where other retail stores will likely open. It’s also a determination of where people decide to live, she says.

“When the grocery stores close, neighborhoods start to die,” Brewer says “Small businesses can’t be supported, people start to move out, and schools close. It’s like a huge domino effect. At the point where there’s no grocery store or school in the neighborhood, it’s dead.”

Source: USDA; modified for the story

Source: USDA; modified for the story