You can always tell when a person has worked in a restaurant. There’s an empathy that can only be cultivated by those who’ve stood between a hungry mouth and a $28 pork chop, a special understanding of the way a bunch of motley misfits can be a family. Service industry work develops the “soft skills” recruiters talk about on LinkedIn — discipline, promptness, the ability to absorb criticism, and most important, how to read people like a book. The work is thankless and fun and messy, and the world would be a kinder place if more people tried it. With all due respect to my former professors, I’ve long believed I gained more knowledge in kitchens, bars, and dining rooms than any college could even hold.

Working in a restaurant, you see the full spectrum of behavior and emotions. The best is in the kitchen, where people from different backgrounds who speak different languages work together. It’s in the enduring friendships made between trips from kitchen to table — full hands both ways, of course — and fortified at the bar once the money’s been counted and the floors have been swept. It’s at the restaurant across the street, where the chef is happy to spare some rosemary because the truck didn’t show, and the bartender has a shot waiting for you when you wander over on your smoke break. It’s at family meal, a service industry tradition other fields really ought to copycat. It’s in a good review and the look in a guest’s eyes when they take that first amazing bite.

The worst is at the table, when you can barely sputter a “Good evening!” before being interrupted by a brash “DIET COKE!” It’s on the line, when you’ve screwed up so badly and you want to yell back, but you know you deserve every curse word being flung your way. It’s at a corner banquette at the end of the night, when you discover you didn’t earn enough tips to cover your car note because Table 18 wrote “Here’s a tip: you should smile more” on their credit card slip. It’s a call from your manager, waking you up before the second shift of your double, asking if you can come in early. The absolute worst is on Yelp, where everybody “really wanted to like this place” but not enough to tell anyone they had asked for sweet potato fries, not regular ones.

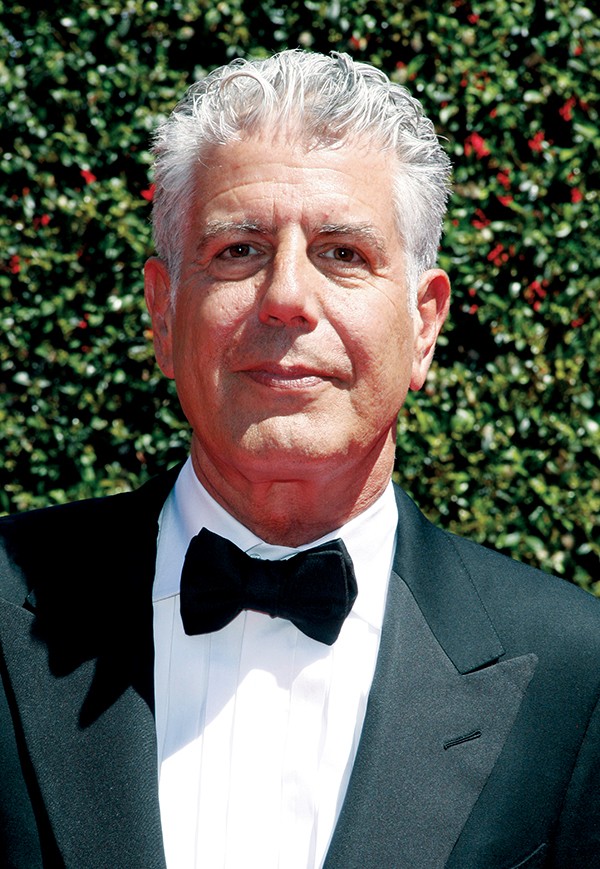

Starstock | Dreamstime.com

Starstock | Dreamstime.com

Anthony Bourdain

I haven’t tied on an apron in years, but restaurant people will always be part of my tribe. The industry attracts a certain kind of individual, whom I consider to be my people. I’m talking about chefs, bartenders, servers who choose standing for 14 hours, enthusiastically describing tonight’s fresh catch, or artfully arranging herbs on a plate as a lifestyle. I get them.

That’s why Anthony Bourdain was so beloved: He got them, too, and sought to elevate them to the status they deserve. We need food to live. Food is integral to every single culture. Nourishment is an expression of love. Bourdain arrived at the onset of the “foodie” craze with a different perspective and a mission to tell stories beyond what’s on the plate. Knowing those stories made everything taste better.

He was a bard. He was an avatar of so many wise and brilliant restaurant people who, at least in my experience, are the best people.

And the best people never seem to stick around as long as you want or need them to. I’ve attended a lot of funerals for restaurant friends who left the world too soon and for unfair reasons. So the grief felt familiar when I saw the news alert on my phone last Friday morning.

With all celebrity suicides come pleas to get help if you feel suicidal thoughts. If those pleas save one life, I’m happy to hear it. While it’s true that no one is immune, anyone who has suffered can tell you it’s not that simple. It’s hard to tell someone’s in pain when the chemicals that inspire genius in the arts — whether they’re the culinary, literary, or performing kind — are the same ones that take creators to dark places. The adrenaline of a Saturday night dinner rush mutes the voices just as an addict’s intoxicant of choice. Bringing happiness to others briefly fills the hole where one’s own joy belongs.

Instead, I’ll offer some different advice, straight from the pages of Kitchen Confidential: Never use a garlic press. And if you ever get an opportunity to talk shop with a chef, bartender, or another service industry lifer, sit down and listen. They’ve seen some stuff.

Jen Clarke is an unapologetic Memphian. Follow @jensized on Twitter.