We’re a nation and a city that likes to eat and eat a lot.

Memphis just wrapped up its annual barbecue contest that turns Tom Lee Park into a festival of pork and beer. For two years in a row, Men’s Fitness magazine has recognized Memphis as one of America’s Ten Fattest Cities. We like fried chicken, fried catfish, and fried pies. The ads and restaurant listings in this and other newspapers are a testament to Memphians’ love of food that’s good, if not necessarily good for you. On the Food Network this week, celebrity chef and “intrepid tourist” Rachael Ray shows viewers how to eat out in Memphis on “only $40 a day.”

$40 a day? Are you kidding?

There is another side to the story. In Shelby County, 178,000 people get food stamps. According to the Tennessee Department of Human Services (DHS), the average allotment for recipients is $96.69 a month or $22.47 for one week. Local DHS counselors say monthly payments range from less than $50 to over $1,000 for a single mother with 10 children. An impoverished single person with no income or housing, for example, would get $155 a month in food stamps, but, earned income, welfare, and other assistance typically reduce that amount. All told, Shelby Countians received more than $18 million in food stamps for the month of April.

Following the lead of four members of Congress who also took the “National Food Stamp Challenge” in May, two Flyer reporters set out to see what it is like to eat on $22.47 for one week. The food stamp program is up for reauthorization this year, and some members of Congress are calling for an increase in benefits.

In a Memphis grocery store, $22 doesn’t go very far. Fresh fruit such as apples at $1.79 a pound or fresh fish at $4.50 a pound takes a big bite out of the budget. Cheaper cuts of meat, whole chickens, hamburger with a high fat content, canned tuna fish, potatoes, milk, dry cereal, and pasta are good budget stretchers and reasonably healthy and filling. Potato chips, soft drinks, and other snacks are budget busters. So are even occasional meals at fast-food restaurants, where a meal can easily cost $5.

A $22 budget does not lend itself to healthy eating. Just the opposite appears to be true, which helps account for the presence of cities with large percentages of poor people on those “fattest city” lists.

“Most food stamp recipients seem to purchase high-starch foods and high-fat foods that are less perishable than fresh fruits and vegetables,” says Sandra Shivers, head of the Tennessee Nutrition and Consumer Education Program at the University of Tennessee. “However, less healthful food choices in the long term tend to cause increases in weight rather than weight loss. It is difficult to make healthful food choices on a limited budget.”

Richard Dobbs, director of food stamp policy for DHS, says food stamps supplement rather than replace the entire food budget for most recipients, with earned income, school free-lunch programs, and local food banks filling the gaps.

“Once upon a time, the federal minimum wage of $5.15 an hour was supposed to be sufficient to keep a person off food stamps,” says Dobbs.

That is no longer the case. Even the $10 an hour “living wage” approved last week by the Shelby County Commission would still make some people eligible for food stamp assistance. For a family of three, the food stamp threshold is a monthly gross income of $1,799, which is slightly more than the $1,600 a month a person would earn working 40 hours a week at $10 an hour.

In emergencies, the Metropolitan Inter-Faith Association (MIFA) will issue families vouchers for a five-day supply of food from one of 32 local food pantries. The amount differs by family size, but for a single person to get the minimum amounts for a nutritionally balanced diet, the pantry should give them four cans of vegetables, three cans of fruit, three packages of dried milk, cereal, pasta or rice, peanut butter, tuna, peas or beans, two “main dishes” such as canned beef stew or chili, and a loaf of bread. By Flyer calculations, that costs about $22.

“If you are getting food stamps, sometimes at the end of the month, you might run out,” says Ina Lang, MIFA’s food pantry coordinator. “You might have a power outage or something, and your food spoils.”

MIFA sees about 25 to 30 families each day. That number spikes in the summer when children are out of school and do not have access to free breakfasts and lunches, and during holidays.

“It’s just not enough to carry them through the month,” Lang says of the program’s clients. “At the first of each month, we have a slowdown because people are getting their checks and their food stamps are coming in.”

Dobbs says the key to a reasonably healthy lifestyle on food stamps is “plan your menus and your leftovers.”

Flyer reporters quickly learned that in our experiment. Here’s what we bought and what we ate.

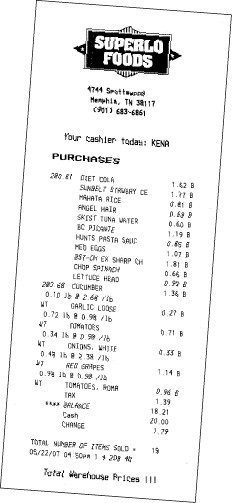

John Branston’s shopping list

Bread ($1.49); peanut butter ($1.39); can of chicken broth (79 cents); box of Spanish rice mix (79 cents); box of Hamburger Helper ($2); gallon of 2 percent milk ($3.33); two pounds hamburger ($4.90); one pound carrots (89 cents); one can of tomatoes (89 cents); one can black beans (89 cents); three pounds of white potatoes ($1.49); three ears of corn ($1); one box of generic-brand corn flakes ($1.99); one-pound bag of long-grain rice ($1); half-dozen eggs (79 cents). Total: $23.63. (There is no sales tax on food stamp purchases.)

dreamstime.com

dreamstime.com

Midwestern baby boomers like me were raised to believe milk would keep you healthy if you didn’t eat or drink anything else. A gallon would cover cereal and one meal each day. Carrots and corn were a nod to fresh food. Lean hamburger and $1.49 bread costs more but goes farther. The total of $23.63 was over target by $1.16, but DHS assumes there is something in the pantry at the beginning and end of the week. In this case, I did not count coffee, tea bags for iced tea, one pack of saltine crackers, salt and pepper and spices, margarine, and a half jar of jelly.

Friday: Breakfast of coffee, cereal and milk, toast and jam. Lunch of Spanish rice mixed with canned tomatoes and black beans with water to drink. Dinner of peanut butter sandwich and milk.

Comment: Rice mix was hearty, tasty, filling, and should last three meals.

Saturday: Breakfast of coffee, cereal and milk, and toast. Lunch of scrambled eggs, toast, crackers and peanut butter. Dinner of corn, baked potato, milk, and a hamburger.

Comment: Hungry, but the big hamburger helped.

Sunday: Breakfast of cereal and milk, toast, and coffee. Lunch of leftover Spanish rice mix. Dinner of leftover hamburger on bread, carrots, milk, and crackers with peanut butter.

Comment: Good thing I like leftovers. Crackers and peanut butter are filling.

Monday: Breakfast of cereal and milk, toast and coffee. Lunch of Spanish rice leftovers. Dinner of hamburger casserole made with one pound of burger plus Hamburger Helper, one ear of corn, and milk.

Dreamstime.com

Dreamstime.com

Comment: Hamburger casserole tastes better than it looks, but it is supposed to make five servings. I ate almost half of it, or about 700 calories’ worth.

Tuesday: Breakfast of cereal and milk, toast, and two scrambled eggs. Lunch of leftover casserole. Dinner of more leftover casserole, peanut butter sandwich, milk, and carrots.

Comment: I have lost a few pounds but am not too hungry. My wife says the casserole smells pretty good. But who has a scraper in the age of baby carrots?

Wednesday: Breakfast of cereal and milk, toast, and coffee. Lunch of rice cooked in chicken broth with curry powder and a peanut butter sandwich. Dinner of the rest of the rice plus an ear of corn and milk.

Comment: Rice is tasty and broth gives it flavor and some calories.

Thursday: Breakfast of cereal and milk, coffee, toast, and last two eggs. Lunch of peanut butter and jelly sandwich, crackers, raw carrots. Dinner of baked potato, milk, carrots, and crackers.

Dreamstime.com

Dreamstime.com

Comment: Last day and a good thing. No meat, nothing left but part of a jar of peanut butter and half a bag of rice from the original shopping trip. In the real world, I would scrounge some free pizza or fruit to fill up.

Freebies for the week: One beer from a friend at a Redbirds game, one beer at a Saturday-night music event, one banana, two diet Cokes, one bowl of instant oatmeal scrounged from office break room as a snack.

Best buy: Gallon of milk.

Best dish: Zatarain’s Spanish rice mix with black beans and tomatoes.

Worst buy: None. No margin for error. You buy it, you eat it.

Cravings: Not-from-concentrate orange juice.

Out of the question: Eating out, wine, fresh fish, and fresh vegetables.

Registered dietician Carrie Barker comments: “You were consuming an average of 2,200 calories each day, including the food freebies you listed. You need an estimated 2,600 calories a day to maintain your current body weight, so it’s no wonder you lost weight.” — JB

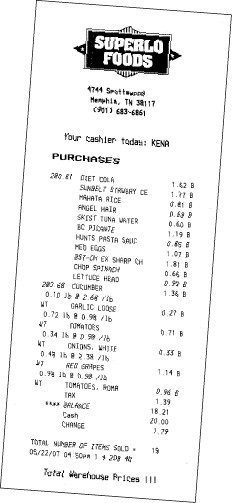

Mary Cashiola’s shopping list

Box of cereal bars (eight for $1.77); a pound of rice (81 cents); pound of angel-hair spaghetti (68 cents); can of tuna (60 cents); jar of salsa ($1.19); can of pasta sauce (85 cents); dozen eggs ($1.07); cheddar cheese ($1.81); frozen spinach (66 cents); head of iceberg lettuce (99 cents); two cucumbers ($1.36); garlic (27 cents); tomato (71 cents); five Roma tomatoes (96 cents); onion (33 cents); three two-liter bottles of generic soda ($2.43); red grapes ($1.14); half-loaf of bread (79 cents); small jar of peanut butter ($1.37); small jar of honey ($1.50). Total: $21.29.

Dreamstime.com

Dreamstime.com

The cheery sign hanging above the mountains of artichokes, blankets of leafy greens, and bundles of asparagus is mocking me. “Five a day for better health” it reads, right underneath a picture of a happy sun.

The sun may be smiling, but I am not. I am determined to include fresh fruit and vegetables in my food stamp diet, but it is not going to be easy.

Some, like Representative Jim McGovern of Massachusetts, one of the congressmen who took the “food stamp challenge,” say it can’t be done. I think he’s probably right. I have roughly $22 for the week. And fruit — even in early summer — is expensive.

Navel oranges are $1 each. A bag of regular oranges is $6. A package of six Red Delicious apples is $1.98.

I have my heart set on red seedless grapes, which are priced at $2.38 a pound. I pick up a normal-sized bag and place it on the scale. It’s a friggin’ pound and a half. That’s no good.

I replace it and pick up a much smaller bag. Think six grapes on a twig. This I can afford.

My colleague John Branston planned his week’s food in meals. I think this is the smart way to go. But if I bought things I never eat, I wouldn’t last a day.

To maintain both a healthy diet and one with enough calories, the experts say to cook foods from scratch and avoid snacks and empty calories. Prepackaged foods are out, as are convenience foods. Not that it always happens that way.

“People want to be able to have snack foods at home,” says Donna Downen, an agent with the local office of the University of Tennessee’s agricultural extension office who specializes in consumer sciences. “At the grocery store, you can buy potato chips with food stamps. I can’t tell you that you can’t use your food stamp money on chips, that you need to buy fresh potatoes.”

When planning my budget, I started with my own personal staples, those things I simply cannot live without — cucumbers, tomatoes, cheddar cheese, and soda — and worked around them.

I end up buying a box of cereal bars, rice, angel-hair spaghetti, one can of tuna, a jar of salsa, a can of pasta sauce, a dozen eggs, cheddar cheese, frozen spinach, a head of iceberg lettuce, two cucumbers, garlic, a tomato, five Roma tomatoes, an onion, two two-liter bottles of generic soda, and the red grapes. My grand total is $16.82, which means I have about $5.50 for the end of the week. I assume I’ll have to spend that on starch or maybe bread and peanut butter. Other than the soda, I plan on drinking water.

Dreamstime.com

Dreamstime.com

Day one goes okay. I eat a cereal bar for breakfast and have my usual salad and grapes for lunch. But I didn’t consider a mid-afternoon snack. By 5 o’clock, I’m ready to go home. I’ve got to eat.

I make rice with spinach and sautéed onions for dinner and pop open my generic soda. Instead of eating the entire two servings, I put some rice aside for tomorrow’s lunch, but I’m hungry enough to eat it all now. I debate: How much can I eat now? How much will I need tomorrow?

This will be my downfall: portion control. Downen says maintaining portion sizes and buying the right foods are the only ways to eat healthily and stay within budget.

“Sometimes people are so hungry, they eat more than they should,” she says. “A lot of times we say, I don’t want to have the same thing two days in a row. But if you buy something that’s four servings and you only eat two, nutrition-wise, you get the most economic benefit if you eat it the next day. But most times we don’t want to do that.”

When I wake up the second day, I’m hungry. I eat a cereal bar before work, but I’m feeling a little light-headed on the drive in. The feeling subsides by mid-morning, but I eat another cereal bar just to make sure. This means I am down to one cereal bar a day for the rest of the week.

Lunch is the rice concoction from last night — I remember that I hate day-old rice — and a salad. On the other hand, I do love cucumbers. And the tomato is sweet and hearty. I savor it.

Dinner is an omelet, with spinach (saved from last night’s dinner), tomato, onion, and cheese. It is very good.

On day three, some of my friends are getting together for a pasta dinner. I have never looked so forward to a potluck.

By this time, I have realized that my diet is simply not sustainable. I’m liking the food that I’ve chosen, but it’s simply not enough. I’m being driven to distraction by hunger.

The dietician’s report confirms my feelings. My daily caloric intake should be 1,710 calories per day, but my daily average for the week is only 1,600.

For the rest of the week, I have cereal bars for breakfast and salads for lunch and the rest of the eggs for protein. I save my grapes for the last day’s lunch.

Dinner one night is rice and tuna, and the rest of the days, dinner is spaghetti with sauce and cheese. I use the rest of my budget for peanut butter, half a loaf of bread, honey, and another soda and add it to the mix for a cheese sandwich and what my mom used to call honey bear sandwiches for snacks.

I am ashamed to add that the one thing that kept me going was knowing that my hunger pangs were only temporary.

“Unfortunately,” says Sandra Shivers, with the University of Tennessee Extension Service, “we do have individuals who have no other food source other than food stamps.

“Your experiment is a realistic view of what food stamp families go through, but remember: They go from week to week with no real end in sight. We have seen individuals who do a good job of managing these resources, and we have seen some who do not. It is possible to live on this amount per week, but, as you see, it takes a great amount of work.”

Freebies for the week: two chocolate chip and raisin cookies and half a strawberry at a lecture, three adult beverages at a dance club, a piece of pizza at a get-together.

Worst buy: the salsa. I thought I would use it on rice and with my omelet, but I didn’t.

Best buy: I’ve gotta go with the angel hair and sauce. For roughly $1.50, I got a good four meals out of it. Of course, I could have done better. A pound of angel hair is supposed to be eight servings. — MC

dreamstime.com

dreamstime.com  Dreamstime.com

Dreamstime.com  Dreamstime.com

Dreamstime.com  Dreamstime.com

Dreamstime.com  Dreamstime.com

Dreamstime.com