“Chickenization” is a term coined by journalist Christopher Leonard to describe a phenomenon that has become ubiquitous in the American economy in the 21st century. In his 2014 book The Meat Racket: The Secret Takeover of America’s Food Business, he traced the trajectory of Tyson, the giant corporation that controls the vast majority of poultry produced in this country.

Beginning in the 1960s, Tyson was a pioneer of vertical integration — owning every link of the supply chain necessary to make your product — by buying up 33 competitors and stripping them of valuable assets. Then, armed with the data they collected from running every aspect of the operation, they outsourced the less profitable portions to independent contractors. In this case, that means small farmers who, in times past, had a number of food companies competing to buy their chickens. But since Tyson owns everything from the feed mill to the slaughterhouse, now the small farmers have to play by the rules the monopolist lays down. As a result, the chicken farmers “own” the dirty and expensive parts of the poultry business while Tyson controls the profitable portions, and there’s no way for the farmers to get ahead. People who used to be employees with benefits are now expected to bear the cost of their own employment.

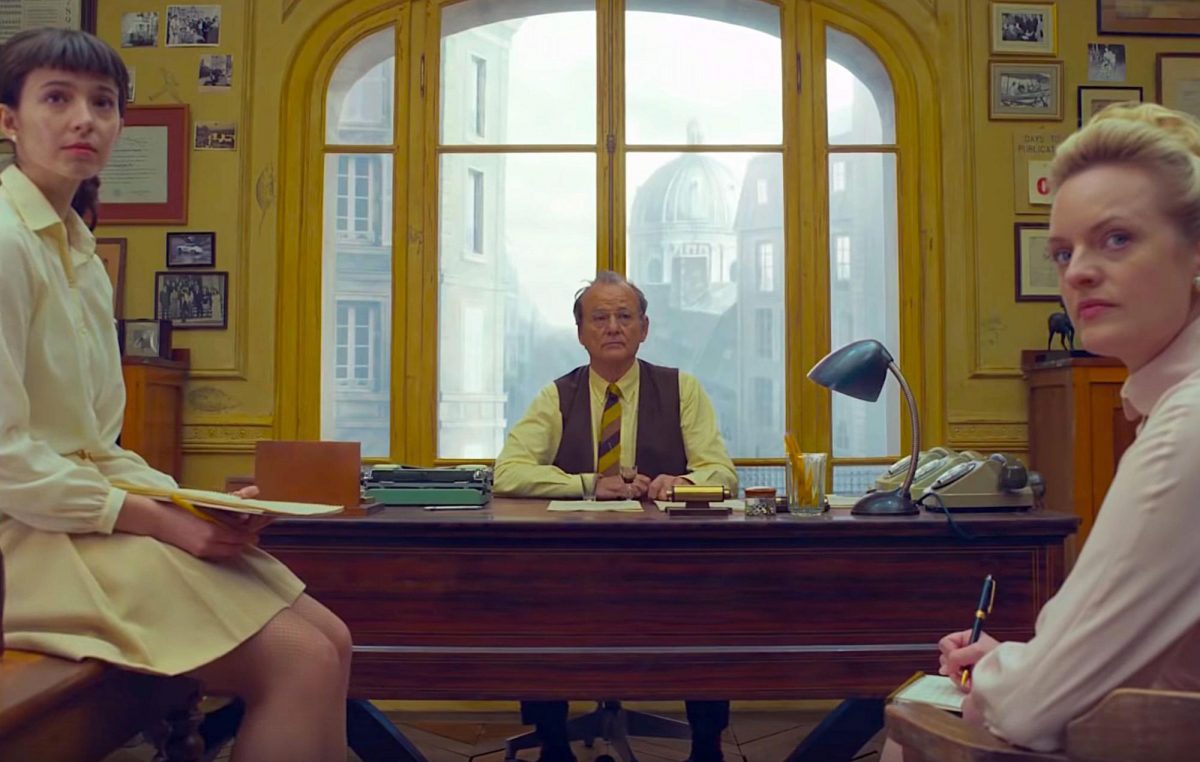

Frances McDormand plays Fern in Chloé Zhao’s Nomadland, based on the 2017 book by Jessica Bruder.

Chickenization has spread throughout the economy. Uber drivers completely depend on the company’s largesse to assign them rides, but they are stuck with the cost of maintaining their own cars. When Leonard visited towns in Arkansas whose economies are dominated by Tyson, he called it “feudalism by another name.”

In Nomadland, Fern (Frances McDormand) is experiencing the endgame for the fully chickenized worker. She and her husband lived in Empire, Nevada, where they both worked in the same gypsum plant. Fern’s middle-class lifestyle suffered a fatal one-two punch when her husband died unexpectedly and the plant shut down. With the town’s sole economic engine gone, everyone moved on, and her home, which represented all of her wealth, became worthless overnight.

Fern sells what she can, puts the rest in storage, and buys a van. She roams through the American West, going from one seasonal contract job to another. When the story opens, she is working the Christmas rush at an Amazon fulfillment center and living, along with dozens of other members of the precariat class, in an Amazon-subsidized RV park.

Is there a purer example of the Orwellian use of language in late-stage capitalism than “fulfillment center”? It sounds positively transcendental. But the reality is a vast, bleak building powered by disposable people.

Fern’s predicament is driven home early in director Chloé Zhao’s film. Laid off as soon as the holidays subside, and unceremoniously informed she’s being evicted from the trailer park, she spends New Year’s Eve alone, wearing a battered “Happy New Year!” tiara while passing out sparklers to her neighbors.

As the trailer park exodus begins, Fern learns of a gathering of nomads in the Arizona desert, run by real-life van-dwelling YouTuber, Bob Wells. In the remarkable scenes that close out the film’s first act, Fern learns survival skills and, for the first time in a long time, feels like she’s part of a community. She also meets Dave (David Strathairn), a ruggedly good-looking nomad who takes an interest in her.

Like Hillbilly Elegy, Nomadland was adapted from a nonfiction book about the ignored and rapidly growing American underclass. But Nomadland lives up to the social realist tradition of The Grapes of Wrath by portraying Fern’s quiet dignity. McDormand’s performance might just be the best of her storied career.

Zhao’s direction has one foot in the DIY underground. She and McDormand took to the van life for months during filming, capturing scenes set in real places, like the famous South Dakota roadside mecca, Wall Drug. Spectacular vistas of little-seen parts of the American landscape representing the freedom of the open road contrast with the dreary reality of the small towns where Fern scrambles to find work and keep her van running. When Fern is finally forced to swallow her pride and ask for help, there is real tension. Will she choose the illusion of self-sufficiency or a modicum of comfort and security at the cost of dependence on others?

Messy, morally complex, and never less than moving, Nomadland brings to mind Ma Joad’s final words: “They can’t wipe us out, they can’t lick us. We’ll go on forever, Pa, ’cause we’re the people.”

Nomadland is showing at Malco Paradiso, and streaming on Hulu starting Feb. 19.