There’s a strange contradiction in the hearts of performers. On the one hand, being the center of attention of a large group of people (“public speaking”) regularly tops surveys of people’s biggest fears. On the other hand, being the center of attention of a large group of people is the ultimate goal of any performer. If you want to get rich — or even make a living — as a musician, you’re going to have to be able to thrive in conditions that the vast majority of people would call hell.

That’s the big takeaway from Amy, the new documentary on the rise and fall of Amy Winehouse directed by Asif Kapadia. This is the director’s second documentary after 2010’s excellent Senna. But while the story of Formula One racing legend Ayrton Senna was mostly triumph, Winehouse’s story is a slow-motion tragedy that makes for a much more complex and challenging film.

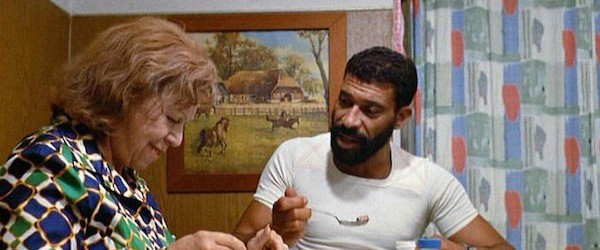

As in Senna, Kapadia uses all archival footage stitched together with a keen editing eye. There are no talking heads — the few contemporary interviews are all presented as voice-only under relevant footage. We first meet Winehouse in 1998 at age 14 singing “Happy Birthday” with her friends Lauren Gilbert and Juliette Ashby. Her prodigious talent is already evident, even though she’s just a fresh-faced “North London Jewish girl,” as Island Records president Nick Gatfield calls her. Even then, she was a woman out of time. As Britpop and hip-hop dominated the London airwaves and the beginnings of dubstep seeped through the underground, Winehouse was idolizing Ella Fitzgerald and Tony Bennett. Her first producer Salaam Remi puts it, “She had the styling of a 70-year-old jazz singer.”

There’s no shortage of images of Winehouse as a dead-eyed junkie, but Kapadia is able to show her humanity, because he won the trust of her first manager Nick Shymansky, who happened to obsessively chronicle her early tours with a handheld digital camera. Of all the people in her orbit, Shymansky comes off the best. He apparently had a bit of an unrequited crush on Winehouse, but even after she fired him in a fit of pique, he still had her best interests at heart. That is not true about literally anyone else she surrounded herself with after her 2003 album Frank became an unlikely hit in England. She started hanging out at London’s trendy Trash nightclub, where she met her husband Blake Fielder-Civil. If you’ve ever known a pair of mutually reinforcing junkies, you already know what their relationship was like. Booze, pot, coke, crack, meth, heroin — you name it, they took it. Fielder-Civil was also a musician, but when Winehouse became the biggest star in the world in the mid-2000s, he became a professional enabler.

Not that Winehouse needed much enabling. The film depicts her as never recovering from her parents’ divorce at the age of 9. She was severely depressed as a teenager and a bulimic from age 15 until she died at 27. She wrote the songs that propelled her to stardom as a way to deal with her many issues, but it was one song in particular that seemed to have doomed her. “Rehab” was written about a failed intervention Shymansky, Gilbert, and Ashby staged for her, which was squelched by her increasingly careerist father. It was kind of an afterthought on the carefully crafted Back To Black album, but when it became her biggest hit, it took on the air of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Amy functions a companion piece to Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck. The two self-destructive musical prodigies had similar trajectories, but they were treated differently by the press and public. Cobain’s junk-induced suicide was an unexpected tragedy, while the world was practically taking bets on how long it would take Winehouse’s body to give out under the onslaught of a $16,000-a-week polysubstance habit. Amy does not hesitate to point the finger at the gawkers and paparazzi who fed them, even as Kapadia depends on their copious footage to fill out the overly long end of his film. Amy succeeds at humanizing Winehouse but leaves you feeling queasy at your own eagerness to watch the trainwreck.