Bright-eyed, fresh-faced, impossibly optimistic — they stand in their caps and gowns on the cusp of achieving their hopes and dreams, ready to take on the world. That is the vision of the Dreamers — the young immigrants brought to this country as children, planning to make their way in the world, if given the opportunity.

Twenty years ago, the bipartisan Senators Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) and Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) proposed the DREAM Act (Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act) to create a path to citizenship for Dreamers. On June 15, 2012, two years after Congress was unable to bypass a Senate filibuster and pass the DREAM Act, President Obama announced his executive action, DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), and said:

“These are young people who study in our schools, they play in our neighborhoods, they’re friends with our kids, they pledge allegiance to our flag. They are Americans in their heart, in their minds, in every single way but one: on paper. They were brought to this country by their parents — sometimes even as infants — and often have no idea that they’re undocumented until they apply for a job or a driver’s license or a college scholarship.”

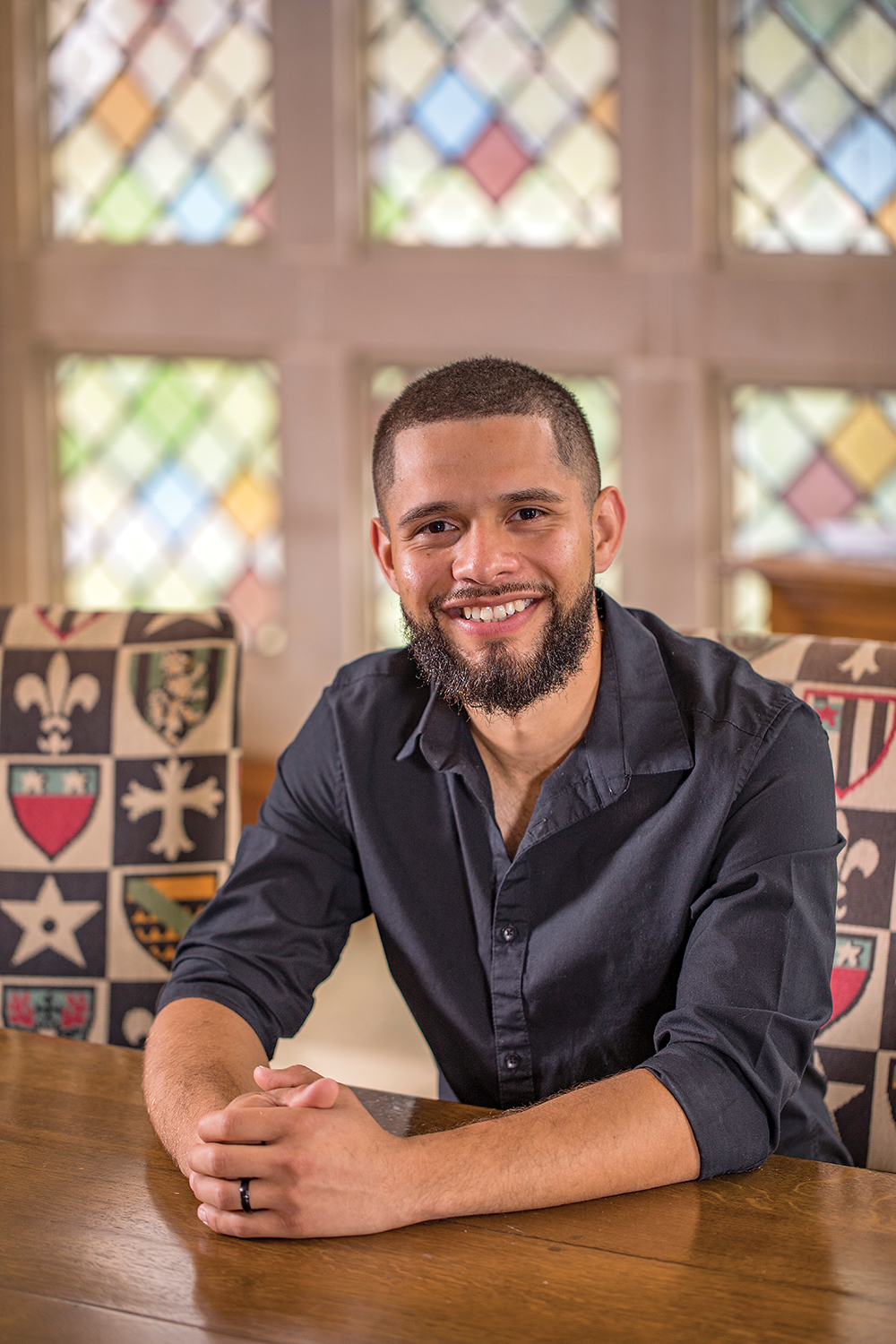

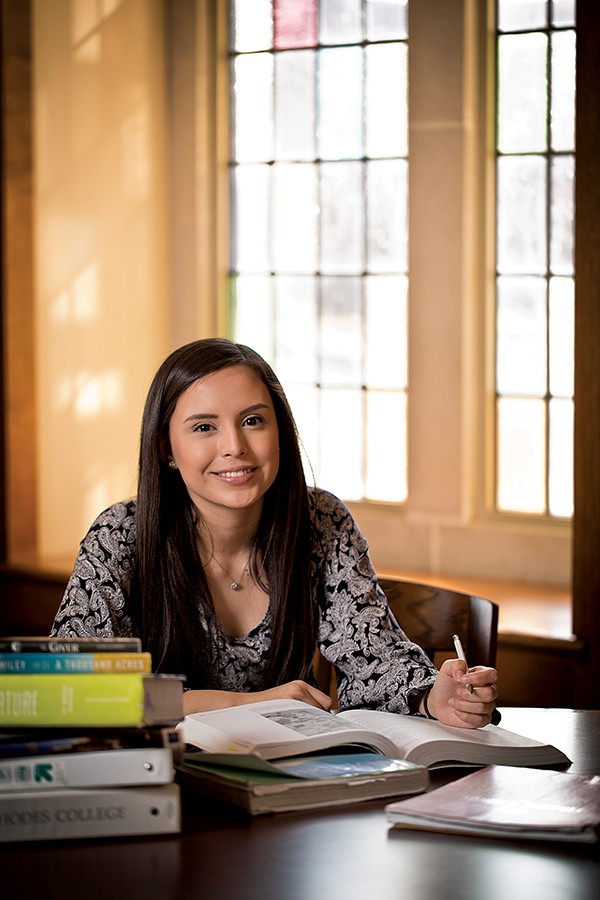

Just over five and a half years ago, on January 14, 2016, the Memphis Flyer published a cover story titled “American Dreamers,” which featured two DACA students, Jocelyn Vazquez and Frankie Paz, who lived here in Memphis. At the time, Vazquez was a senior high school student at Immaculate Conception High School in Midtown and Paz was a first-year student at Christian Brothers University. Just kids!

But like so many DACA recipients, Vazquez and Paz are no longer kids

Dream On

Vazquez and Paz are still living here in Memphis. While the optimism still shines, it has been tempered by lessons we all learn when becoming adults. However, their particular paths to adulthood have been made more difficult by the political realities of the past five years, including a viciously anti-immigration administration in Washington, an insurrection merely five months ago, and a seemingly dim future for the kind of political reform needed to modernize our immigration system.

DACA has given hundreds of thousands of young people the opportunity to stay in the U.S., study here, work here, and contribute to the nation. President Trump tried to rescind DACA in 2017 during the first year of his presidency, but the courts intervened. On June 18, 2020, the Supreme Court ruled against the administration, finding its actions to be “arbitrary and capricious.” The 643,000 young people — their friends and family, teachers and employers — breathed a collective sigh of relief.

Durbin has not forgotten about the legislation he introduced 20 years ago. The Illinois Democrat remains determined to see the DREAM Act pass the Senate, and, speaking from the Senate floor on January 21, 2021, the day after President Biden restored DACA via executive action, he said, “Without DACA, hundreds of thousands of talented young people who have grown up in our country cannot continue their work and risk deportation every single day.” But even he recognizes how the prolonged battle has occurred while the lives of these kids continue to evolve, noting, “These young people, known as Dreamers, have lived in America since they were children, built their lives here, and are American in every way except for their immigration status.”

Making Opportunity Work

For Jocelyn Vazquez, DACA has allowed her the opportunity to study and work with some protection, though she (like all DACA recipients) must re-apply to the program every two years at a cost of $495. Thanks to DACA, according to Vazquez, “I’ve been able to do something with my college degree. I have a driver’s license and a sense of protection.”

She graduated from Rhodes College in May 2020 during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and is now an eighth-grade English Language Arts teacher at Kirby Middle School. She takes a visible pride in the connections she has established with her students, a process that has developed despite the multiple challenges of being a first-year teacher, virtual teaching, and then switching to in-person teaching this past March.

Frankie Paz began college at Christian Brothers University here in Memphis in the fall of 2015; he earned a full scholarship through an arrangement to help Dreamers, offered through an outside foundation in partnership with CBU. Paz studied business with a concentration in sports management but was unable to complete his degree due to shifting family dynamics, health concerns, and work.

However, CBU represented a fantastic opportunity for Paz. On campus, he met supportive people in the administration and on faculty, but he also learned that he was largely on his own — as a first-generation college student, he had little family support and now realizes he was growing up and becoming an adult. “I began to network and learned how to meet people, talk to them, and came to understand that interacting with a wider community is fundamental for success.”

From CBU, Paz took a job with United Airlines. He interviewed for a ramp agent position, but the interviewer quickly saw Paz’s potential and placed him in customer service. United management wanted to move him to Denver permanently, but Paz, in consultation with his girlfriend (now wife), decided their future was with family here in Memphis. He is now working at a company owned by his father-in-law that specializes in customized construction work.

While these professional paths might imitate those of any young Memphian, President Trump’s attempt to roll back DACA presented serious stressors for Vazquez and Paz. Vazquez remembers the tensions associated with waiting on the Supreme Court decision in 2020: “The long three-year period between Trump’s attempt to rescind DACA and the June 2020 ruling created a constant stream of anxiety.”

Vazquez adds that Trump’s anti-DACA rhetoric shaped her thinking about money and savings: “When you don’t know if protections offered here in the U.S. and the safety of home and community will be uprooted from one day to the next, you try to save more money — you never really feel completely safe.”

Mauricio Calvo, executive director at Latino Memphis, underscores Vazquez’s sentiments. He worries about the tremendous human potential that’s wasted as DACA is rescinded, then brought back — i.e., as the political process takes precedence over the needs and aspirations of young people living in our nation. “These DACA recipients have been in a state of limbo for so long. It’s a challenge, and it means people have to make really difficult decisions,” Calvo says. “Does a person decide not to attend law school, given that there is a question about whether she could actually practice law once she graduates? Does a company pass over someone for a promotion because there is a question of what will happen with DACA?”

Paz does not dwell too much on DACA, but it is always lurking in the shadows. The 24-year-old comments how “the threats during the last few years were always there.” He diligently renewed his DACA eligibility documents this past January. He followed the 2020 presidential election, and though he cannot vote, he supported the candidate “who I thought would work to bring the nation together.” Stating the obvious, Paz says, “There’s just too much division here.”

Making Memphis Home

Family dynamics define the day-to-day life of Vazquez here in Memphis. Vazquez’s family has taken full advantage of various opportunities here in the U.S. For example, her younger sister — following in Vazquez’s footsteps — graduated from Rhodes College on May 15th with a bachelor’s in pyschology.

Vazquez’s mother no longer cleans homes for a living; instead, she opened a small restaurant here in the city, reflecting the determination, drive, and resilience of our neighbors. Her father has shifted his work from construction to property management and real estate. Her parents, especially her father, still retain the belief of so many first-generation immigrants that if you work hard enough in America, you will be successful. Vazquez’s experiences and the tenuousness of DACA, however, have left her a little bit skeptical of that notion.

To a close observer of experiences like Vazquez’s and Paz’s, “potential” is the word that best defines DACA recipients. Daniel Connolly, a reporter and author, has been covering immigration and the local Hispanic community for more than a decade. Connolly authored the critically acclaimed 2016 work of immersive journalism, The Book of Isaias: A Child of Hispanic Immigrants Seeks His Own America, which is a moving account of Kingsbury High School student Isaias Ramos and his family as they navigate life in the U.S. — in Memphis.

“These young people — it’s in the interest of society to help develop their potential,” says Connolly. The hope, optimism, human capacity, and youthful promise of kids like Paz, who was also featured in his book, continue to inspire Connolly.

Developing and nurturing the potential of DACA youth makes sense for purely practical reasons: The 643,000 current DACA recipients arrived here on average when they were seven years of age and have lived more than 20 years in the United States. They are the parents of 250,000 U.S. citizen children. It is estimated that, over the next decade, Dreamers with DACA who continue to work legally in the United States will contribute $433 billion to this nation’s GDP and will pay more than $12 billion into Social Security.

While the Dream Act languishes in Congress — 20 years on — and the politicians in Washington throw DACA around like the political football it has become, the young DACA kids grow older and become adults. “While the political fight goes on, the DACA youth are moving on with their lives,” notes Connolly.

The journalist gently brings up the Samuel Huntington paradox. In 2004, Harvard political scientist and cultural theorist Samuel P. Huntington (d. 2008) published a polemical book, titled Who Are We?: The Challenges to America’s National Identity. Huntington predicted a total social, linguistic, and cultural bifurcation in the U.S. based on immigration and data trends from Latin America. “Samuel Huntington,” comments Connolly, “wrote of a societal split and tried to frighten us by writing of a Spanish-speaking minority that never assimilates.” The journalist continues, “It’s actually the opposite of that — people are quickly finding their place in society, and this is a very hopeful sign for this nation.”

Up until a couple years ago, Paz lived with his mother in Memphis, but he moved out on his own and settled in an apartment complex in Midtown. Ironically, his neighbor in the same complex was Daniel Connolly. This was a certain sign for the Memphis journalist that Huntington was simply wrong. Integration was prevailing past the Harvard theorist’s bifurcation.

Paz — a newlywed — recently moved to East Memphis with his wife and has grown through his experiences. He has learned how the concept of family expands and evolves as the years progress and told us about gaining expertise in “budgeting, how to live and share with another person, how to be a better person.”

Vazquez said she loves Memphis and wants to stay here as an educator. “I lived in a big city [Houston, Texas], and a small rural town in Mississippi — Memphis seems like a perfect balance between those two extremes.” She is getting ready to move into a rental home near the Crosstown Concourse in the city she has chosen as her home.

Paz, together with his wife, plans to work in property investment here in the city; Memphis is home. “I see such great potential in this city, so much improvement and such opportunity for growth.” Paz has been here for a dozen years; as a two-year-old, he traveled with his family from Honduras to California and then to Memphis.

Calvo reminds us why it is so critically important to listen to the stories of Vazquez and Paz. “You know, generally, as a society, we become less sympathetic to people as they grow older,” states the Latino Memphis director, a bit wearily. “We need to understand that DACA didn’t solve the larger problem, it merely cracked the door, and that door can be closed. It’s cruel to show them the possibilities in America while not finishing the [legislative] job and giving them a full and unhindered chance at life.”

Like so many DACA recipients, Paz and Vazquez continue to move forward and have grown from young idealistic teenagers into adults confronting the realities of life’s challenges. They are our neighbors. They have chosen Memphis. As Paz says, “I can see myself staying here. I have only vague memories of Honduras. I want to build something in Memphis. … I want to contribute to Memphis.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks