More and more Memphians are missing out on the American Dream, especially if you consider homeownership a centerpiece of that dream. Wall Street corporations are sucking up homes in struggling neighborhoods, spitting them back out as rentals, and — in doing so — sucking out wealth and access to upward mobility, particularly in African-American communities.

Some experts on this crisis call these corporations “vultures,” saying they use tactics comparable to the mafia. Across the country, they’re scooping up houses in low-income neighborhoods — sometimes by the hundreds — wringing what profits they can from them, leaving the empty shells, and moving on. The experts call this a “pump and dump” strategy. These companies sometimes use evictions as a way to get back rent, as well as levying fines and fees on tenants, a strategy designed to push profits even higher.

It’s a national problem, but Memphis is the poster child for it. Last year, 65 percent of Memphis’ single-family homes were rented, not owned. The figure was enough for Zillow, the real estate website, to list Memphis as the country’s fastest-growing rental market in 2018.

That rental rate is a massive statistic, given that more than three-quarters of the city’s housing stock is comprised of single-family homes. Investor groups and large corporations own 95,604 of those properties; more than 40 percent of those owners are from outside of Tennessee. It’s probably fair to say they don’t have the city’s — or their own tenants’ — best interests at heart.

“All these guys want to do is to maximize the short-term gain,” says Austin Harrison, a researcher from Georgia State University and a housing consultant, during a recent event in Memphis. “They don’t inspect the properties. You’ll hear stories about mold, or the plumbing or the electricity not working. They don’t fix anything.”

Those who’ve studied the issue say the problem runs deeper than real estate. It gets down to poverty, often cited as the city’s greatest scourge. How can we beat poverty here, experts ask, if African Americans can’t build wealth through homeownership in a majority-African-American city?

“As if the Great Recession’s foreclosure crisis of 2007-2008 was not bad enough, more than a decade later, instead of a phoenix rising from the wake of the burst housing bubble, the vultures have descended upon the housing market in Memphis,” reads a policy paper released recently from the University of Memphis’ Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Change. “The result is a policy crisis and the exacerbation of the wealth and racial division in the city.”

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

Robert Holden, who is currently experiencing homelessness, very generously allowed himself to be photographed as he looked through a “picker pile” — the de facto symbol of Memphis’ eviction crisis.

Frayser: “Prime Feeding Ground”

Steve Lockwood sees outside corporate involvement in Frayser housing every day. He’s the director of the Frayser Community Development Corporation (FCDC), and as he drives in his silver pickup around the community of about 45,000, it seems he knows just about every house.

He thinks outside investment in neighborhoods like Frayser is, simply put, “bad.” Local brokers and developers sell the community’s homes to big firms all over the world, from California to New Zealand, he says. But at least two real estate players in Frayser do good work, Lockwood says, and are “good actors.” So he tries to work with them.

“Our objective all along has been to work on market forces, rather than pretend we could do it all ourselves because we can’t, and we know that,” he says.

One of them, a local broker, buys up homes, cleans them up, and does “perfectly good work,” Lockwood says. He paints his renovated houses in a signature red, gray, or green. Lockwood says even if the developer’s houses result in more renters, rather than creating new homeowners, the homes at least help revitalize the rest of the neighborhood.

On a recent tour of Frayser, Lockwood points to four concrete slabs, PVC tubing still stuck out of the ground where plumbing was planned. The development failed — 25 years ago — but the slabs and pipes remain. It’s part of the “funk” that still pervades parts of Frayser, he says.

Less than a mile from the slabs, siding was going up on one of several new homes by a builder Lockwood likes, another “good actor” making real estate money in Frayser, he says. Lockwood and the FCDC connect potential homeowners to that builder. The group helps people get approved for loans and sends them to the builder, with no commission or any money changing hands. “We’re just trying to affect the neighborhood,” Lockwood says. If the FCDC doesn’t help the builder find local buyers, he may sell to out-of-town investors.

“I’m still trying to tip the ratios here, or figure out at what point is this no longer prime feeding ground for investors,” Lockwood says. “I’m afraid it’s prime feeding ground for quite a while yet, and there’s not much I can do about that.”

Remember the Recession?

It’s hard to know if Frayser is a prime target for Wall Street investors. But Frayser certainly was one of the the hardest hit by Wall Street in the wake of the Great Recession.

Frayser was the foreclosure capital of Tennessee, according to the FCDC. The 38127 ZIP code saw the most foreclosures in the Memphis area every year from 2000 to 2015. Those foreclosures gutted Frayser, leaving vacant houses all over the community.

But it wasn’t only low-income communities like Frayser that were hit. Foreclosure rates all over Memphis shot up 13 percent in the first half of 2008, compared to the same time the year before, according to a Memphis Daily News story by Eric Smith, published in September 2008.

“Foreclosure’s reach knows no bounds, no race, no limit on home value, no restriction on loan product,” Smith wrote. “Its reputation as being constrained to only the poorest parts of town dissipated long ago, and while it’s true that foreclosures historically have occurred in marginal neighborhoods where minority borrowers were targets of bad mortgages, foreclosure is happening frequently and with ferocity in suburbs such as Cordova, Arlington, and Collierville.”

As we know now, the national economy — and Memphis — has rebounded. The “Memphis has momentum” slogan helped Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland win another four years in office this year. Much of that momentum was pushed ahead by payment-in-lieu-of-taxes (PILOT) deals given to real estate developers, principally designed to help spur the economy out of the recession.

A 2018 study by Community Lift, a group working to accelerate the revival of the city’s disinvested neighborhoods, says the incentives have worked, for some. While shiny, new roofs sprout in abundance throughout the fertile, PILOT-charged Poplar corridor, many neighborhoods outside that verdant valley haven’t yet been lifted by the rising tide.

“Memphis has been experiencing unequal economic development,” reads a summary of the “Searching for Economic Development Equity” study. “Some neighborhoods are growing while others are stagnating or even declining.”

Lockwood says in the 1970s (when the median household incomes in Frayser were 110 percent of those in Shelby County), many Frayser residents worked at International Harvester or at the nearby Firestone tire plant. When the plants closed, many people left.

He describes much of what happened to Frayser’s population as “middle-class flight,” not necessarily “while flight.” But whatever the reason, when the people left, hundreds of homes were left vacant. According to a May 2018 report by the Frayser CDC, 1,500 homes — 11 percent of all homes in Frayser — were empty.

A research study by Community Lift says buildings in older neighborhoods often don’t meet current standards for warehouses. Therefore, most industries that the city manages to attract or retain choose to locate in industrial zones that have more suitable buildings or available land or new construction options. Blue-collar jobs concentrate in those areas, and white-collar jobs concentrate in the Poplar/I-240 corridor and Downtown, where the Downtown Memphis Commission has led efforts to attract and retain businesses and corporate headquarters.

“Not surprisingly, the neighborhoods experiencing the strongest job growth are the ones near jobs centers, or those that have good transit access to those jobs (Downtown, East Memphis, the Medical District, Midtown, and the University District),” reads the Community Lift study. “Neighborhoods farther away from those job centers have experienced decline or stagnation. Many of the job centers on the fringes of the city are very poorly served by transit connections to places with the highest unemployment.”

But there is a ray of hope in Frayser. In August, plans became public for a “colossal” (according to a Commercial Appeal headline) warehouse planned for 99 acres in Frayser, just north of the Nike distribution center. While no ground has broken on the project yet, Mayor Strickland tweeted at the time that the project was proof that “Memphis — all of Memphis — has momentum!”

The Vultures Return

It’s not really clear just how or why out-of-town investors began taking interest in Memphis’ lower-income neighborhoods. Whatever their motives, the “vultures” are back, according to that U of M Institute for Change study, and they’ve come again from Wall Street.

Wade Rathke is a founder of the nonprofit ACORN International and one of the authors of the U of M policy paper. He says in the “pump-and-dump” strategy, vulture firms will buy homes, slap a couple of coats of paint on them, line up some renters, then maybe evict them if the timing works out. They repeat this process for years, until the money dries up. When it does, the company walks away, leaving a vacant home and big question marks on who to call when the grass needs to be cut or when it becomes blighted.

“These Wall Street guys — if you think of them in the same mindset as the mafiosos — they are predatory landlords,” said Ben Sissman, a Memphis-based foreclosure prevention attorney, during the recent State of Memphis Housing summit. “They’re selling high and doing no work. They deny responsibility for what they’re doing. All they want is the rent money and nothing else.”

A 2018 Washington Post story reported that out-of-town investors bought 20 percent of all homes on the Memphis market last year. Cerberus, a Wall Street private equity firm, was the largest owner of single-family homes in Memphis in 2018, according to the Post.

So how does that affect Memphis? For one thing, such huge holdings could allow companies like Cerberus to have dominance, with the power to drive the Memphis housing market, according to Rathke.

This trend toward corporate housing ownership takes hundreds of homes off the home-buying market that might have been accessible to low- to moderate-income families — including the same families that may have been pushed out of similar homes in the foreclosure crisis, he says.

“Families [moving] in to some of these houses are paying pretty high rent and maybe have a hard time sustaining that,” Rathke says. “So, it’s basically frozen people back to where they were a decade ago. It hasn’t allowed some families in Memphis to get past the Great Recession.”

The Memphis families affected are largely African-American, according to Rathke’s research. “Renter household increases are highest among African Americans, with the total number of African-American renters double the number of white renters,” reads the paper, called “A Memphis Mirage.”

Overall, homeownership in Memphis declined from 66 percent to 59 percent from 2010 to 2017. Since the 2008 financial crisis, no major city has had a bigger percentage drop in owner-occupied single-family housing than Memphis, according to the Washington Post. The percentage of renters rose from 34 percent to 41 percent. Black homeownership fell by 1.2 percent from 2009 to 2017. African-American rental rates increased 26.1 percent during those years. In comparison, white rental rates grew three percent.

Wealth gets sucked from neighborhoods into corporate coffers, as renters replace homeowners. Residents aren’t building equity in a home. When their lease expires, they walk away with nothing to show for it. Building home equity is considered a fundamental building block to creating wealth and financial stability in America. Amy Schaftlein, executive director of United Housing in Memphis, says renters “not only lose equity in their house and the wealth they could have built through homeownership, they also lose trust in ownership as a wealth-building tool.

“We’ve seen so much wealth stripped out of, particularly, minority neighborhoods and neighborhoods with high African-American populations because those neighborhoods were, frankly, targeted,” Schaftlein adds. “That’s just awful because you see so much wealth built and then it goes tumbling. It goes back to the old days of redlining, and you just see it happening again and again.”

Consider the Picker Pile

Yellow hazard lights blink on a Salvation Army box truck as it idles in front of a home on East Parkway. Two men haul a few valuables from the vacant home, but they largely ignore a mini-landfill by the curb. In the picker pile, tube televisions with darkened screens lie helter-skelter with faded furniture, colanders, ice trays, empty dish soap containers, sweaters, jeans, and dozens of VHS tapes. The scene has a front-row view of Tiger Lane and Liberty Bowl stadium across the way.

It has all the hallmarks of an eviction, but it’s hard to know for sure. Maybe the tenant ghosted. Maybe someone died. One thing’s for sure, Memphis is seeing a lot of evictions these days, and the picker pile has come to symbolize their plight. And if you’re seeing more of them than you used to, consider that they may now be the results of investment policies of a Wall Street firm or other out-of-town “vulture capitalist” whose investors have never heard of Liberty Bowl stadium — and care nothing about what happens to the Memphians they’ve put on the street.

Evictions are profit centers for them. Once an eviction is filed in court, says ACORN’s Rathke, the corporations can collect all kinds of fines and fees. “They’re collecting not only their back rent and whatever penalties that were laid out in a lease, but they’re also collecting court fees and filing fees,” he says. “There are some landlords, particularly in lower-income communities in Memphis and other cities, who are basically running this as an income cycle. Often they don’t follow through on the eviction because they’ve made, potentially, the rent plus the penalties.”

From 2016 to April 2019, 105,338 eviction notices were filed in Shelby County General Sessions Civil Court, according to Harrison’s research.

In 2016, 4,593 evictions were filed in New Orleans, 5,909 were filed in Birmingham, and 17,169 were filed in Richmond. In that same year, 31,633 eviction notices were filed in Memphis. Notices here went out to nearly 21 percent of all Memphis renters. Renters who got eviction notices were predominantly African-American, Harrison says.

FirstKey Homes, the property management firm owned by Cerberus, files for eviction at twice the rate of other property managers in Memphis, according to that Washington Post story. FirstKey went to court here more than 400 times in 2018, the story said.

Fighting the Tide

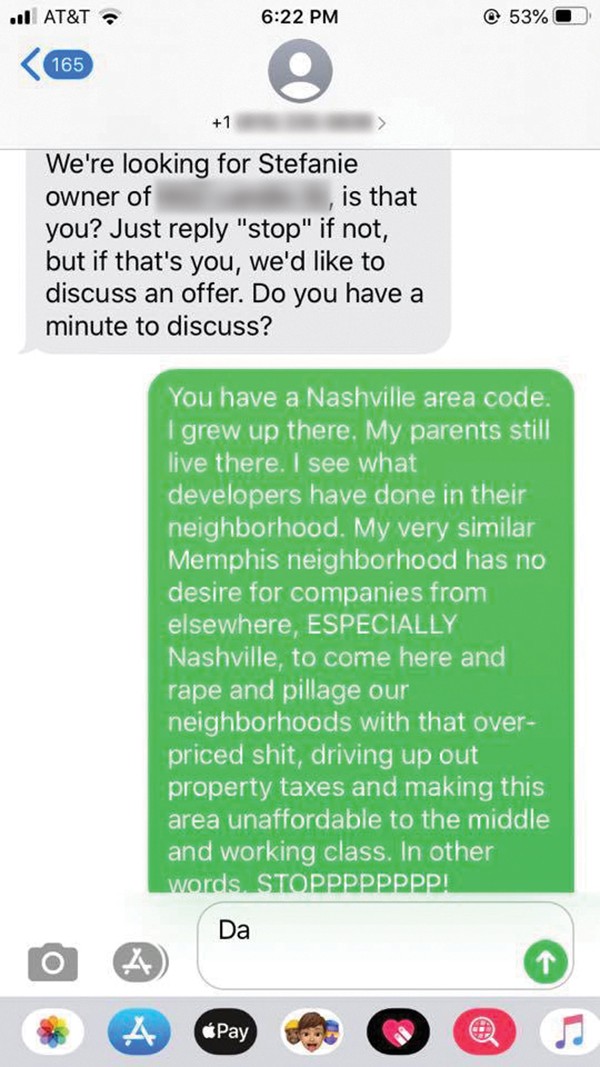

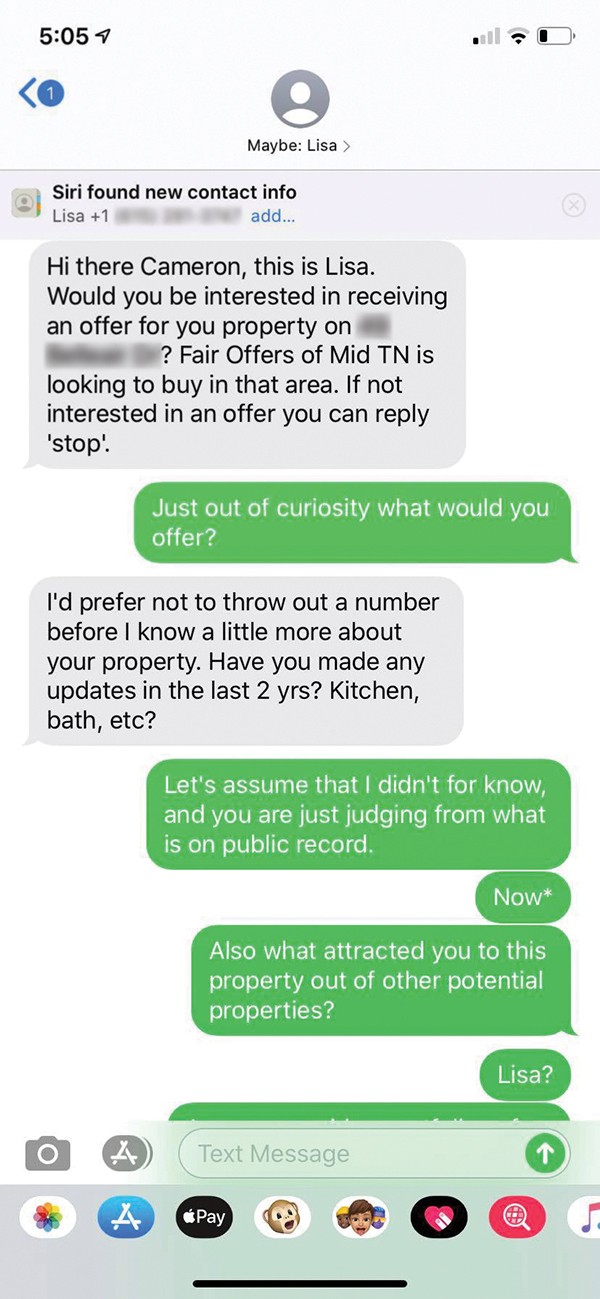

John Paul Shaffer says the members of his neighborhood advocacy group, BLDG Memphis, get uneasy when they see signs that read “I Buy Houses” pop up on their streets. There’s likely an out-of-town investor behind the sign, one with cash readily at hand.

This housing issue would be easier to manage, he says, if it were some thought-out policy. Instead, he, Lockwood, Schaftlein, and the many others working on housing in Memphis are fighting market forces, mostly against anonymous competitors with Scrooge McDuckian piles of capital.

Lockwood’s FCDC has bought, renovated, rented, and sold dozens of homes in Frayser, each with a signature brass plate with the FCDC logo. The group, with the help of some local developers, has almost completely revitalized one neighborhood with targeted, intensive investment and are working on rebuilding another.

Schaftlein’s United Housing is dedicated to sustainable homeownership throughout the Mid-South. The group sells homes, rents homes, offers down payment assistance, offers mortgages, and has funds for home improvement, whether the tenant owns the home or rents it.

Shaffer’s BLDG Memphis is a hub for all Memphis-area community development corporations such as the FCDC. BLDG Memphis helps those organizations fight for better housing in their neighborhoods.

All of them are witnessing the corporate rental-conversion issue first-hand. “This is part of the national narrative, and Memphis has come up as a hotspot,” Shaffer says. “We have a few instances where maybe over 1,000 properties are owned by one particular entity. That creates a lot of issues to provide service if these properties do become nuisances and code enforcement gets involved, and, then, the environmental courts get involved.”

Schaftlein says some renter agreements won’t allow tenants to make repairs to the home, and a run-down house has a ripple effect. A bad house lowers property values, and that can make other homeowners move away, destabilizing entire neighborhoods.

“You see a lack of pride,” she says. “You see a lack of investment. Those who can leave, do. That’s what’s happened in a lot of our neighborhoods.”

Jesse Davis

Jesse Davis

Chris McCoy

Chris McCoy

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

Facebook

Facebook

Chris Shaw

Chris Shaw