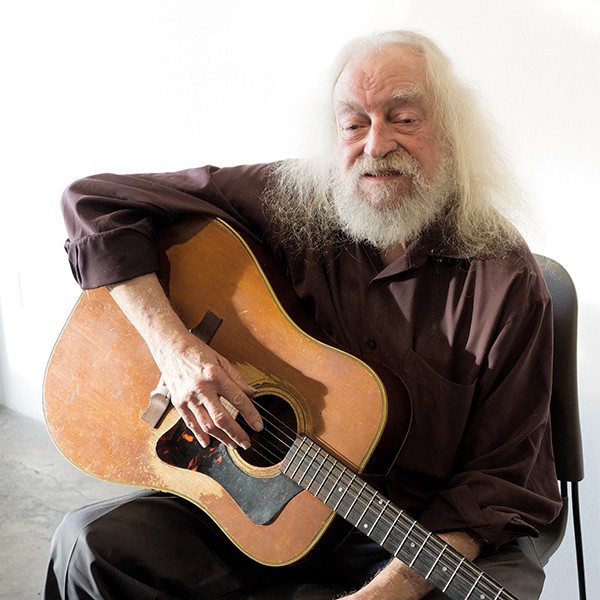

Last week, Memphis lost its most famous unknown blues legend, hippie folk singer, Zeke Johnson. To many who saw Zeke perform at clubs and coffeehouses around town, and to the young musicians he tutored in blues and folk music, he embodied all things Memphis. Looking timelessly old, but with the eyes of a teenager, he had a photographic memory, a mischievous sense of humor, and the refined manners of a Southern gentleman.

Born in 1943 in Mississippi, his family moved to Midtown Memphis when he was 11 years old. After a brief time at Ole Miss, Zeke enrolled in then-Memphis State University, leading to a storied teaching career. From 1971 to 2008, he taught English, theater, history, and humanities at Bishop Byrne High School, Lincoln Junior High School, East and Colonial High Schools, and Lausanne Collegiate School. He was married to the love of his life, Mary Donovan Long Johnson, for 41 years, until her death in 2012.

Cindy McMillion, Courtesy Connecting Memphis

Cindy McMillion, Courtesy Connecting Memphis

Zeke Johnson

As a child, Zeke sang in the church choir. But his musical life really ignited when he saw Elvis play in 1956, and even more so in 1963, when “Professor” Jim Dickinson turned him on to the blues. In 1965, he heard great Memphis blues legend Furry Lewis perform at the Bitter Lemon as the opening act for folk singer Henry Moore.

As Zeke once recalled, “I had no idea who Furry was, but the minute I heard him play ‘John Henry’ I said, ‘I got to know how to do that.'” During a break in the set, Zeke asked Furry to strum the chords a few times so he could secure the progression in his memory. Upon returning home, he immediately retuned his guitar to Vestapol (open D) tuning and began to duplicate what he had heard. By 1974, Zeke was performing as one of Furry Lewis’ regular second guitarists. He was also Furry’s devoted pupil.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Zeke was part of a group of young white artists and intellectuals, including musicians Jim Dickinson, Lee Baker, Sid Selvidge, and Jimmy Crosthwait, who fiercely opposed racism and celebrated the blues. During this time, he played with Booker “Bukka” White, Fred McDowell, John Estes, and Jesse Mae Hemphill.

Though his participation in the local music scene had waned somewhat through the years, his musical life was revived in 2010 when his longtime friend Mary Burns offered to give him a monthly gig at Java Cabana. Burns, the owner of Java Cabana, also passed away recently.

Zeke then became a regular performer at Earnestine and Hazel’s, The Cove, and many more venues around the Mid-South. He also headed the Blues Legends Birthday Series at the Center for Southern Folklore, a monthly celebration of his favorite blues musicians. And he became an avid user of social media with an international following, posting more than 170 video blogs featuring the history and anecdotes of Mississippi Delta and Memphis roots music.

In the last years of his life, he lived with all his heart, writing and recording at least 70 original songs, as well as several tribute albums, including his album, Me and Furry and Them. Since 2014, he recorded and performed with many Memphians, young and old. His playing was crazy and powerful, sounding like a three-piece band, a manic stride piano, and a slide guitar all in one.

Zeke loved all the attention he received in his final role as troubadour sage. As he introduced every song with a story, he would often declare that if his late wife Donovan were there, she would be telling him to shut up and sing. He captivated and intrigued his audiences with a voice that was loud and deep and beautifully clear. As one local player, Kyle A. Carmon, says, “Zeke’s personality was so huge, it really seemed to me like he was gonna live forever.”

The First Congregational Church of Memphis will host a memorial for Zeke Johnson on Saturday, November 23rd, 1:30-4 p.m.