With last Sunday’s Grammy Awards now behind us, we can more easily imagine the many talents that fuel the music industry. Along with headline-grabbing superstars like Bruno Mars, awards went to less celebrated roles, such as “Best Improvised Jazz Solo” and “Best Engineered Album” — offering some all-too-rare recognition for those who hone their craft over a lifetime, more for love of the art than any hunger for notoriety.

Often, in the brave new world of maximum streaming and minimum liner notes, such critical team players get no public credit for their efforts, unless they receive a Grammy nod. For Gebre Waddell, who was attending the Grammys that night as president of the Memphis chapter of The Recording Academy, it must have been especially satisfying. The local music-engineering innovator is used to toiling behind the scenes, but has lately devoted most of his energy to one thing: creating a way to give credit where credit is due in the recording industry.

It is a topic dear to the hearts and wallets of many a musician, especially in the digital age. With the advent of music streaming services like Spotify, musicians, writers, and producers have seen royalty streams run dry in the past decade. Scores of them have been stirred to action, either in high-profile lawsuits from the likes of Neil Young, or through coordinated lobbying by The Recording Academy, the American Federation of Musicians, and other groups. Memphis’ 9th District Congressman Steve Cohen is one of several co-sponsors of the Fair Play Fair Pay Act, which aims to restore royalties to more equitable levels, closing loopholes that currently allow streaming or satellite services to pay next to nothing. In the meantime, the movement marked a major victory last Saturday, when the federal Copyright Royalty Board ruled in favor of a nearly 44 percent increase in royalty rates that songwriters receive from streaming services.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

But the struggle for equitable pay for music innovators is far from over. And, as Waddell explains, it is a moot point if credits are not recognized in the first place. This stems in part from the lack of any universal database for such minutiae. It can have career-damaging consequences. Brian Hardgroove, one-time member of Public Enemy, has noted, “There is a record I produced that won a Grammy, and because I was inadvertently left out of the credits, I missed out on having that award on my shelf.”

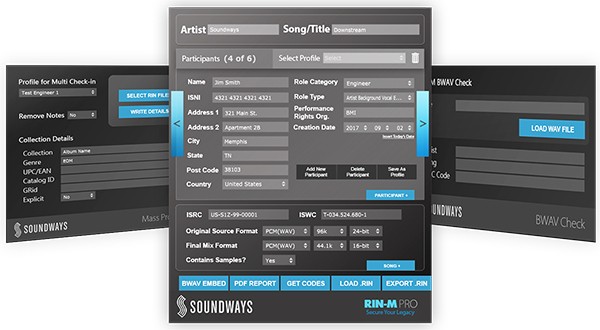

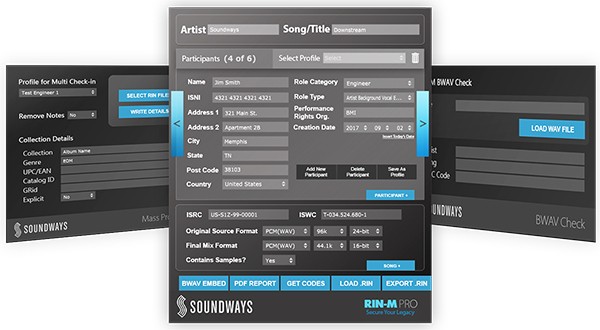

And, as Waddell says, the digital age has thus far not offered much hope for improvement. “It’s gotten worse, because 15 years ago, you could turn over a CD cover and look at the album credits. Today, if you stream something on Spotify you may not find that information at all.” Waddell began grappling with the conundrum of how to make credits more ubiquitous nearly a decade ago, when he was making a name for himself as a music software developer and mastering engineer (about which he literally wrote the book, Complete Audio Mastering, published by McGraw-Hill in 2013). A few years later, DDEX, a consortium of music industry players, created the Recording Information Notification (RIN) standard for registering credits within audio files. But it was all hypothetical: There was no practical tool to make it happen.

“After the written standard was published,” Waddell explains, “it was getting into the end of that 12-month deadline, and if nobody implemented it, it would go under review, and basically it was gonna die. So I was like, well, ‘Let’s save it. Let’s do an implementation.'”

Last year, Soundways, the music software company Waddell co-founded with Chief Technical Officer Connor Reviere, launched a product known as RIN-M to industry insiders. The response was so enthusiastic that this month they are gearing up for the widespread release, including a platform on a dedicated website, of the product, newly rechristened as Sound Credit. It’s a potential game changer for music credits in the digital age. Indeed, with the rapid international adoption of the RIN-M prototype, it may have already changed the game.

“We released RIN-M, and within two weeks, we had users in 50 countries. Today, we have active users in 64 countries, and we are getting information and feedback from these users every day,” notes Waddell. There clearly was a hunger for such a system among music professionals, who naturally have a vested interest in maintaining a credit database. According to the business model, they will be the ones paying for Sound Credit. To the average consumer, it will be free.

While record labels, libraries, studios, and other institutions will pay a subscription fee for the right to submit and edit song credits, listeners will simply see an added “bitly” link adjacent to the track listing, which will take them to the Sound Credit website and an entire database of detailed credits, from personnel involved to the equipment used. Making this information freely accessible is a high priority for Waddell. “People are wanting to see this information, and it becomes a music discovery, too. It makes the story more real. It makes music more human and less of an abstract concept. You start to get into the people behind this. And those stories are what have drawn so many people into music to begin with.”

Aside from last year’s industry-only adoption of Sound Credit, Waddell has been laying the groundwork for his game-changing software on other fronts. High-level talks with Apple and other tech giants last fall have helped shape the product for consumer use, and talks with Avid, parent company of ProTools, have helped them craft ways to make it attractive to the denizens of recording control rooms. Credits for songwriters, engineers, producers, musicians, and others can be associated with tracks even as they are being created in the studio. The goal is to interrupt studio workers’ workflow as little as possible.

But what of the credits for nearly a century of recordings pre-dating the RIN protocol? Waddell smiles craftily. “We have historical information on over 100 million songs,” but he’s hesitant to reveal how the data has been compiled. “We don’t want to introduce that into the public database yet, until after what we call the charter phase. The charter phase of Sound Credit will be a time when we are making sure that this fits the needs of the present while also anticipating as much as possible about the future. With database design you want to make sure that what you have is is pretty solid on the front end.”

If it rolls out this month as planned, and gains momentum, Sound Credit could easily become an industry standard — and a lucrative investment. “The closest company in this space is Gracenote. They are a music data company, and they were just recently acquired for $560 million,” Waddell explains. “Music data is big business.”

If profit was Waddell’s only motive, he would have left Memphis years ago, when big industry players were offering to buy the rights to the mastering and audio production software that Soundways was already marketing. Two years ago, Waddell made a life-defining decision: He would keep control of Soundways and keep it in Memphis.

His reasoning derives equally from civic responsibility and self-interest. He envisions the city once again making a name for itself as a home for innovators. And even if we have no MIT, Waddell thinks it’s achievable. “With tech, if you don’t have a formal education, it doesn’t matter as long as you have the experience and the ability. And I think that appeals to the Memphis spirit in a way. I heard Jim Dickinson describe us as ‘renegades.’ We make our own rules. We make our own paths, and that matches with the tech world — it’s such a perfect fit.”

Soundways RIN-M was developed to help music makers and music lovers keep track of song credits.

“I feel like doing this project and doing it here in Memphis is part of what gives it its strength,” says Waddell. “If you’re in Silicon Valley, just making software and you’re just gonna say, ‘Yeah, we’re doing music credits today, and we’ll be doing medical records tomorrow.’ It’s nothing like hearing those vivid stories of people being affected by it, culminating over decades in music, and wanting to deliver something. There’s nothing like that motivation.”

Waddell also has some very personal reasons to ensure that artists get their fair shake. “Most people just need to see some sort of symbol that it’s possible. When people see a great bass player at church or a great drummer, and then they hear the stories of people going to Los Angeles and playing with Stevie Wonder, you see all these pathways out. And when I say out, I don’t necessarily mean just out of Memphis, but out of a bad neighborhood. I grew up in Orange Mound. You’re looking for ways to raise your prospects.”

Stressing the influences of his family environment, Waddell says, “A lot of talent has come out of Orange Mound. It has real historical significance with the black community. It was quite unprecedented.”

Not surprisingly, the role of an unacknowledged artist played a major role in Waddell’s upbringing. “My father [James Waddell] was a sculptor, but he struggled his whole life. He did two sculptures of Martin Luther King Jr. that are just amazing. Ernest Withers took some pictures of my father when he was working on them. And yet my father struggled with depression, from never reaching any measure of success after [creating] these hundreds of sculptures in his lifetime. He didn’t have a talent for marketing, and not being able to reach an audience was a limitation.”

Waddell’s mother gave him a sense of those less fortunate around him. “My mother was a social worker for 30 years. She was familiar with the toughest situations, where children have been terribly abused or malnourished. She would bring that home with her.”

And having played in Memphis bands and engineering recordings since the age of 15, the crusade for credits took on a personal dimension. “Any night of the week, you can go out in Memphis and hear stories of broken friendships,” he says. “Coming from the perspective of the musician and the working artist. Ten-year friendships are broken because someone didn’t get proper credit on an album. You’re hearing that disappointment of a lost legacy. They put everything into their work, into their craft, and they don’t get credit.”

If the path from Orange Mound to software innovator seems unlikely, it was essentially a product of pure gumption. “We had a computer that none of my family wanted to use,” Waddell recalls, “and so it was put in my room. It was an old Texas Instruments that I hooked up to a TV. It could take cartridges, but we didn’t have cartridges; we just had a book, and if you wanted to play a game, you had to type in the code. If you turned it off you had to retype it. So at six or seven years old, that was what I had to do.”

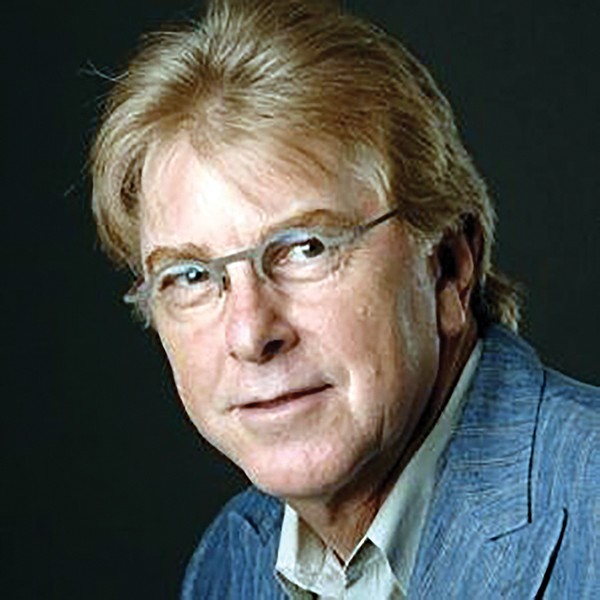

Gebre Waddell speaks at an audio developers conference in London.

Such propensities led him to experiment with the internet in its earliest days. “I had a bulletin board system [BBS] before there were websites, before the World Wide Web was as we know it today. I was 13 years old and I ran a BBS on my parents’ fax line. Once we started getting into the World Wide Web, I started getting into website design, and I did that throughout my teenage years, while also playing in bands.”

Waddell’s facility with the internet also gave him advantages as his love of music began to take him into the realm of audio mastering. “I wrote an article I put on my website called ‘The Digital Publishing Standards,’ which started to get 50,000 to 100,000 hits a month. It attracted the attention of the Google search algorithm, and after a while, if you typed in ‘CD mastering’ into Google anywhere in the world, my website would be the first that would appear. And that allowed me to build out mastering clients in all these foreign markets. I was one of the first mastering engineers working that way, so it wasn’t uncommon for me, in my mid-20s, to work on an album for an artist in India in the same day that I would work on one from New Zealand. I pioneered that sort of international approach to mastering.”

His interest and notoriety led to him to accumulate different perspectives on mastering, and his personal notes became the basis of what is now the chief textbook on the subject. Meanwhile, he dove into the realm of software design, as his book research and practical experience fed off each other. When the offers came in to sell the rights to his innovations, he held back and stayed put. Memphis is still where you’ll find him today, and, he says, where you’ll find him tomorrow. “Having a company from Memphis is such a strong symbol, so that was this big part of the decision to do my own company. I took a dive, I took the risk.

“I’ll never forget this: I went to an audio developers conference in London and I spoke at the conference. Afterward, I met someone from Google, and we had a few drinks, and I said to him, ‘I heard you say “y’all” a few times. You must be from the South.’ And he said, ‘In Silicon Valley, it’s really looked down upon. That accent does not work out there.’ You could just see it was a big issue for him, and he suppressed that accent as much as he could. And for me, that was a moment where I was like, ‘I want to do something where it’s undeniable that the technology is coming from here.'”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks