Local civil rights leaders are opposing a new bill that will allow the use of deadly force to prevent personal — or personal property crimes.

House Bill 11 would allow citizens to take matters into their own hands if their personal property is being violated. At first glance, the bill seems reasonable, but local civil rights leaders fear that it will put innocent people in direct danger.

“Similar to what happened to Ahmad Arbery in Georgia, they perceived him to have stolen something in that house then they chased him down and killed him,” said Rev. Walter Womack of the Southern Christian Leadership Council. That incident turned out to be a case of mistaken identity, where neighbors thought a man jogging in their neighborhood was a criminal.

ShelbyCountyTn.gov

ShelbyCountyTn.gov

Van Turner

Van Turner, president of the Memphis chapter of the NAACP, raised the same concerns.

“This is a piece of legislation that comes from nowhere in the midst of a pandemic,” he said. “Every day, for the last two weeks, I’ve gotten a report of someone that I know who has passed from COVID-19. In the midst of all this death and despair, the efforts of our Tennessee General Assembly should focus on relieving folks from this.”

The Tennessee bill seems much like the Castle Doctrine Law better known as the ‘Stand Your Ground law,’ where individuals have the right to use reasonable force, including deadly force, to protect themselves against an intruder in their home.

The difference in the House Bill 11 and the Castle Doctrine is that the language states “When and to the degree the person reasonably believes deadly force is immediately necessary to prevent or terminate the other from committing or attempting to commit the following offenses …” This means that the person being violated would not have to be in immediate danger, themselves.

Under current law, if a suspect is running away from the scene of the crime, you cannot legally shoot at them. If this bill is passed, a citizen can do so without penalty.

Tn.gov

Tn.gov

Jay Reedy

Rep. Jay Reedy, who sponsored the bill, argues that citizens should have the right to protect their possessions. “I would like to understand why people should not be able to protect their property, and I’m waiting for a returned phone call from the NAACP.”

As soon as the NAACP posted their grievance about the law, Reedy says his office tried to to call and set up a meeting to hash out the language in the bill. Turner said that he has not received a call from Reedy’s office.

“The bill is so vague that if you thought that someone stole from you, then you can kill them,” said Vickie Terry, Executive Director of NAACP, Memphis. “It’s racially based and since it is a statewide law, it’s a kind of loophole for shooting unarmed people.”

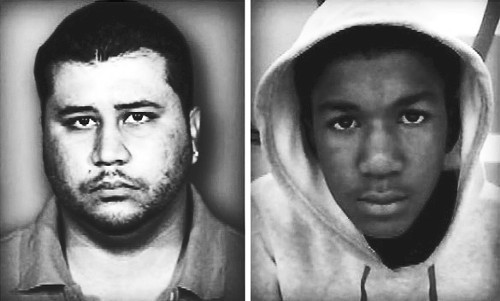

The law raises the case of Trayvon Martin, where George Zimmerman took it upon himself to profile and shoot the unarmed teen because of his perceived threat against the community. “You can’t allow people to just go and deputize themselves and take the law into their own hands,” said Womack.

The timing isn’t appropriate. Plus, the focus should be on people and not things” said Turner. “The measure would promote even more violence in the city.”

The bill, which was filed several weeks ago, is slated to go to the state house floor in early 2021. The session starts January 12th and probably won’t be heard in committee until the end of January or early February.