“We serve two complementary groups of people in Memphis,” says Ryan Watt, executive director of Indie Memphis. “We serve the filmmakers and artists, to help their work get seen, and help with things like grants and workshops and panels and networking opportunities. We help artists from Memphis and beyond get their movies seen. On the other hand, we serve the audiences who are dying to see something different. I like superhero movies, too, but there’s only so much of that we can see.”

For 18 years, Indie Memphis has pursued those twin missions. What began with movies projected on a sheet in a downtown bar has evolved into one of the city’s premier cultural events. This year brings big changes to the festival, beginning with Watt, who took over as director earlier this year after the departure of Erik Jambor. Watt, a producer with seven features under his belt, was an Indie Memphis board member who volunteered to be the interim director after the January resignation of Jambor. In September, what was originally a temporary position became permanent. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I thought that would be it. But we started the search for executive director, and I got about a month into it, and I thought, ‘I’m really enjoying this.'”

This year’s festival expands to eight days, from November 3rd-10th, to allow audiences more opportunities to see movies that might have gotten lost in the shuffle in the former four-day format. “We kept the weekend, which is the anchor of the festival, and we added screenings before and after it,” Watt says. Friday through Sunday screenings, panels, parties, and events will take place at Circuit Playhouse and Studio on the Square in Overton square, while the rest of the festival will take place downtown in the Orpheum Theatre’s new Halloran Centre.

The festival takes place late in the film calendar, which means Indie Memphis can get unique films. “The Sundance and South by Southwest films have made the rounds and already have distribution. But we’re a month before the big Oscar push, so we get movies like Carol and Anomalisa and Brooklyn. Other festivals don’t get those,” Watt says.

One of the most buzzed-about films at the festival is Tangerine, director Sean Baker’s comedy that was shot entirely on an iPhone. “I think about that movie on a daily basis,” Watt says. “You think about the movies that change independent film, like Clerks or Pulp Fiction. Tangerine will be on that list.”

Director Whit Stillman

In addition to bringing the cutting edge of film to Memphis, the festival also celebrates classic cinema. The groundbreaking indie Metropolitan will get a 25th-anniversary screening, with director Whit Stillman on hand to answer audience questions and, on Saturday, conduct a screenwriting panel. For the centennial of Orson Welles’ birth, the festival is partnering with Rhodes College to screen his 1965 Shakespeare adaptation Chimes at Midnight, which the director considered to be his best film. “This is a big deal,” Watt says. “We’re showing a 35-mm print. Only a handful of copies exist in the world.”

With a new online ticketing system and a plan for expanded year-round programming, Watt wants to make sure Indie Memphis rounds out its second decade bringing even more big-deal events to the city.

Andrea Morales

Andrea Morales

Joann Self Selvidge and Sara Kaye Larson worked for four years on The Keepers

The Keepers

This year’s crop of local films is the strongest in recent memory. The festival opens with The Keepers, a documentary by Memphis directors Joann Self Selvidge and Sara Kaye Larson. The pair met at a dinner party hosted by photographer William Eggleston in 2011.

Larson is a survivor of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. “One of my first films I was recognized for was, I did a super-D.I.Y. film where I videotaped everything while I was going through chemotherapy in the early 2000s.”

Andrea Morales

Andrea Morales

The idea for The Keepers came from Larson’s daily walk through Overton Park. “I was obsessed with the Zoo,” she says. “I wanted to go behind the scenes. I’d always wanted to make a real documentary. Joann said, ‘I do too!’ And that’s how it happened.”

Self Selvidge has produced and directed documentaries for 11 years. Her most recent work, The Art Academy, detailed the history of the Memphis College of Art. Her close collaboration with Larson was a first for her. “We’re both used to doing everything ourselves,” Self Selvidge says. “She and I actually think a lot alike. We have way more similarities than differences. We had lots of friction in certain areas and a lot of opinions. And it made the film stronger. I’ve always worked with really strong people and a strong crew. I didn’t go to film school. I’ve learned by doing it, and I learned from other people.”

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Carolyn Horton and Kofi the giraffe

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Fred Wagner, the big cat keeper

The pair shot more than 300 hours of footage during the four-year production. “The biggest thing we want Memphis to know about this movie is that they’re going to get unprecedented access behind the scenes at the Zoo. The whole point of making this movie was to answer documentaries that rely on sensationalism. It doesn’t matter if zoos are good or bad. What about the people who work there? What is their experience? Connecting to zoos through the eyes of the worker, it’s going to give you a perspective that you have never seen before,” Self Selvidge says.

Larson says the finished product ended up being far different from the film the directors thought they would be making. “When we went into it, we thought, ‘This is going to be such an interesting story, because we’re going to film people that love animals, but yet they have to take care of them in captivity. They’re going to be so conflicted. This will be a great story.’ But guess what? They’re not conflicted. They’re fine with it. And they should be. They’re totally zen.”

But for the Grace

But for the Grace

Emmanuel A. Amido came to Memphis at age 12 as a refugee from war-torn South Sudan. “The first four or five years are kind of a blur, because I didn’t know the language or understand the culture,” he says.

His interest in filmmaking began when his mother bought a digital camcorder. “During birthday parties and events, I always wanted to be the one holding the camera. During my junior year of high school, I took a media class. Our final project was to produce a little newspiece. I loved it. That was the first time I got to edit. That’s when I decided I was going to do this for a living.”

Amido’s films are shaped by his immigrant experiences in Memphis. “I’m very fascinated by American society. In such a short period of time, so much has happened. When you look at the world timeline, when America came into the world, it’s like nothing. But in that short period of time, it was established, developed, and surpassed nations that had been around since Moses. That’s fascinating to me, the idea of democracy, and rights, and privilege.”

His first film Orange Mound, Tennessee: America’s Community won the Soul of Southern Film award at 2013’s Indie Memphis. “It was going to be about the violence of Orange Mound, but when I started making it, it became something else,” he says. “I wanted to make something that the people of Orange Mound could celebrate. A lot of people I met were beat up and worn down from the struggle and the poverty. So I wanted to make something to lift them up.”

In But for the Grace, Amido explores questions of faith and race in contemporary America. “I started with Martin Luther King’s quote that Sunday morning is the most segregated hour in America. I went in to look at some of the issues that keep churchgoing Americans segregated. I wanted to move along both socioeconomic and racial lines. But as the movie progressed, I discovered that race is still a very touchy subject for people to talk about in the church, on both the white side and the black side. So I focused more on the racial side.”

Amido’s unique perspective allows him to conduct frank discussions on race relations with people on both sides of the Sunday-morning divide. “America is not a perfect society, not by a long shot. But what I like about being here is that even though it’s imperfect, even though there’s a lot of inequality, somebody like me, who’s not even from here, can make a documentary calling people out on these issues. I’m not saying that after this movie comes out, blacks and whites are going to hug each other. But I’m able to do that, and there are people who will see it, and will think about it, who don’t think they have to defend a certain point of view. The majority of the world doesn’t have that, and Americans take it for granted.”

Girl in Woods

Girl in Woods

“We sort of made the movie twice,” says Memphis native Jeremy Benson about his psychological horror movie Girl in Woods.

After completing and selling his 2008 film Live Animals, he and his producing partner Mark Williams were trying to sell investors on a vampire film. “We were in a pitch meeting, and the investor said he liked the business plan, but he didn’t want to be attached to that kind of story,” he recalls. “I blurted out that I was working on a short story about a girl with some mental problems who gets lost in the Smoky Mountains. From that statement to about two months later, we had the money, but we didn’t have the script.”

Over the course of an 18-day shoot in East Tennessee, the crew, which included ace Memphis cinematographer Ryan Earl Parker, battled the elements. “We underestimated how hard it would be to shoot in the mountains. Out of the 18 days we were there, it rained nine of them. It looks great in the movie, but it really slows you down.”

Juliet Reeves London, who plays the lead character Grace, turned in a nuanced performance despite the harsh conditions.”Juliet was a trooper, having to shoot around snakes. She’s in 90 percent of the movie. She does a great job.”

But when Benson got the hard-won footage back to the editing room, he and editor Brian Elkins discovered their problems were only beginning. “We cut it, but there were big sections of the story that were not coming across like they should.”

So the crew convinced their investors to finance a series of reshoots that would add a backstory in flashbacks that was previously told in dialogue. “We went back and shot half the movie again,” Benson says. “Honestly, I’m glad we did it. I’m 10 times more proud of this cut than I was two years ago. It forced us to go from the in-town, D.I.Y.- style to getting a casting director, go through the unions, and get a breakdown, and do it the way we’re supposed to do it.”

The reshoots added Buffy the Vampire Slayer star Charisma Carpenter and Party of Five‘s Jeremy London to the cast. Girl in Woods is also the last film role by the late Memphis actor John Still, who was a fixture in Craig Brewer’s films. The finished film is dense and twisty, not relying on gore and jump-scares to build tension. “It’s a horror film, but it’s definitely pushing the genre in all sorts of different directions.”

Benson says the movie is a tribute to the power of persistence. He recalls asking experienced filmmakers for advice on how to improve after his first film. “And they always said ‘Just do it.’ We thought they were being sarcastic. But after doing it, we realized they were telling the truth. You just do it.”

Wind Blows

Syl Johnson: Any Way the Wind Blows

“Syl’s story really found me,” says director Rob Hatch-Miller. The New Yorker met the soul singer in 2009 while filming for a radio station’s website. “I didn’t know a lot of his music at the time. I knew his name, and I knew he had a reputation for being sampled a lot in the hip-hop world. But I didn’t know much beyond that. Seeing him interviewed that day, it was clear that he had a fascinating story about his career in music and that he was a fascinating character. He’s a super interesting guy: funny, quirky, great personality. The character is the most important part of deciding to do a documentary.”

Johnson is not as well known as Al Green or Marvin Gaye, but he had an astonishingly prolific career that spanned three decades. “He’s not someone who made one album and disappeared. The boxed set of his album that was nominated for a Grammy while we were filming is six LPs, and that doesn’t even cover half of his career. He did everything, from early 1960s, heavily blues-influenced R&B music, to super funky James Brown-style hard funk, to Hi Records-Memphis-style, to even doing some great disco-y stuff towards the end of his main recording career. His music went on to influence hip-hop in a major way, as much as James Brown or Al Green influenced hip-hop. Syl’s song ‘Different Strokes’ from 1967, recorded in Chicago for an independent record label, is one of the most sampled songs of all time.”

Johnson is a native of Holly Springs, Mississippi, and the film brought him back to the Memphis area. “We were going to these places in Memphis with Syl that he hadn’t been for years, seeing people whom he hadn’t seen in years,” Hatch-Miller says. “Hearing these stories that we had only had glimpses of previously, it was a really exciting time filming, and probably the most fun we had shooting. You can see it in the scene when he shows up at Hi Records where all of the stuff was recorded with Willie Mitchell and Al Green and Syl and Otis Clay and O.V. Wright. It was a wonderful day. The audience walks in the door with him and meets the family of Willie Mitchell, and you really feel like you’re being taken back in time. It’s one of my favorite parts of the film.”

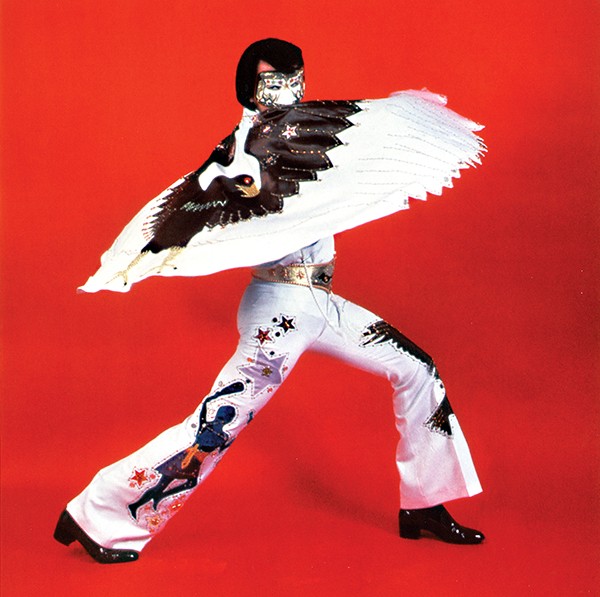

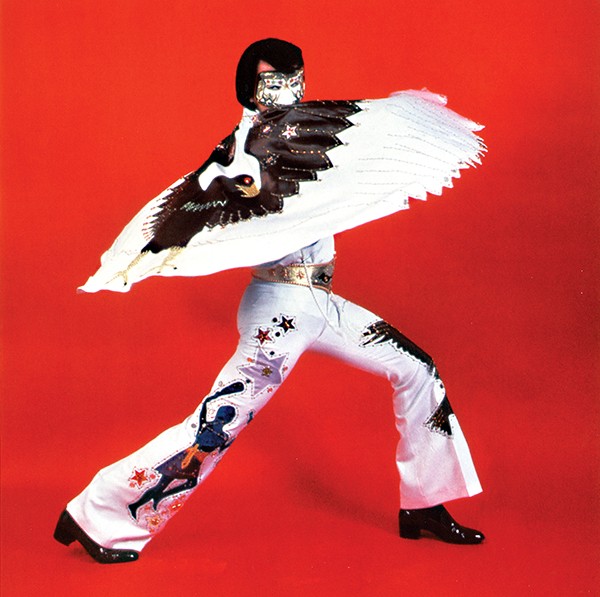

Orion: The Man Who Would Be King

Orion: The Man Who Would Be King

Twelve years ago, English director Jeanie Finlay was at a car boot sale — “You would call it a yard sale” — when she found an old vinyl record called Orion Reborn. “On the cover there was a man with a mask, his hands on his hips, and big hair. For a pound, you can’t go wrong! So I took it home and played it. It was confusing. It sounded like Elvis, but it was after Elvis died. It was on Sun Records. What’s going on here?”

She went on to forge a career as a documentary filmmaker, but she never forgot about the mystery of Orion. She struggled for years to get funding for Orion: The Man Who Would Be King and traveled to the States to shoot whenever she could. “I never gave up. I feel like filmmaking sometimes is a test of your own resilience,” she says.

She gathered together 80 hours, 5,000 images, countless hours of archival material, and 337 crowd-funders before winning backing from Creative England, Ffilm Cymru Wales, BBC Storyville and Broadway. “Once I had gotten all of those things in place, everyone else came on board. There’s no magic bullet when it comes to making films. I felt possessed by Orion’s story, and I knew that one day, in some way or another, I was going to make it into a film.”

Orion’s Elvis-esqe appearance and singing style was cooked up by Sun Records, at that time owned by Shelby Singleton, and was the origin of the persistent myth that Elvis faked his death. “People just want it to be true. Every time there’s something people want to be true, those are the stories that go viral.”

Finlay says Orion: The Man Who Would Be King, which closes Indie Memphis, is, like all her films, “about what music means to people. It’s a different take on the things that were going on in the wake of Elvis’ death. Elvis is not actually in the film, but he casts sort of a long shadow over it. It’s funny, it’s moving, and it’s surprising.”

Andrea Morales

Andrea Morales  Andrea Morales

Andrea Morales  Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon  Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon