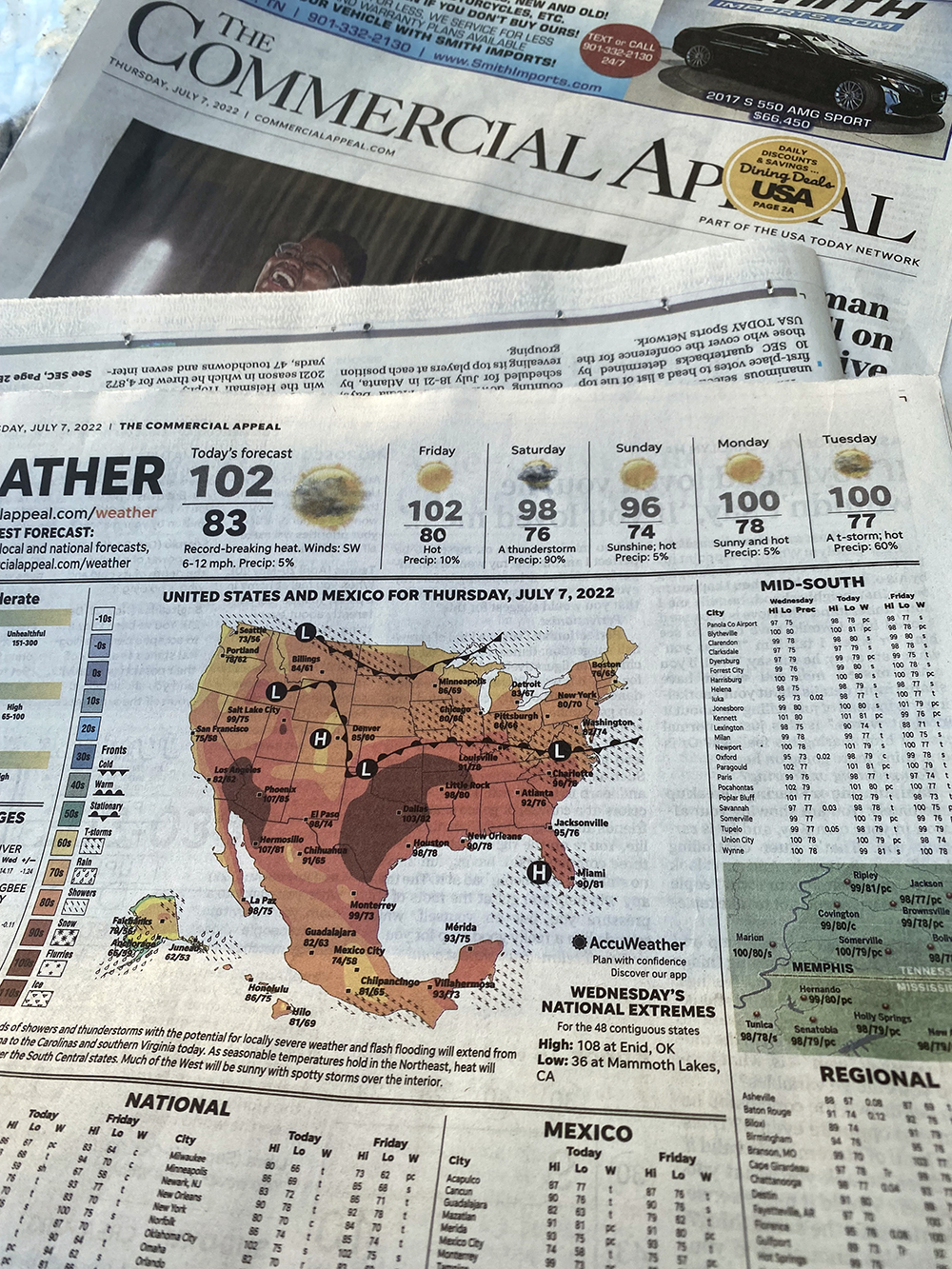

In a couple hundred years or so, some scientists say, Memphians who want to go to the beach will just pack up the car and head down to the river bluffs. They believe global warming could raise ocean temperatures and cause the polar ice caps to melt completely. The result: a dramatic rise in sea level that could swallow current coastal cities, eventually bringing the coastline up to Kevin Kane’s front porch.

Far-fetched? Not according to Jerry Bartholomew, chair of the University of Memphis earth sciences department. “Memphis will be beachfront property,” he says. “All of the major cities along the coast — Philadelphia, Baltimore, Miami, Tampa, Charleston, New Orleans — would be underwater. If you raise sea levels 300 feet, they’re under 300 feet of water.”

It may sound like a gloom-and-doom scenario, but more than 20 percent of the polar ice caps have melted since 1979, according to The Weather Makers, Tim Flannery’s new book on climate change.

Only time will tell how quickly the caps will melt — or if the melting will continue — but most scientists now agree that the earth is undergoing some sort of warming trend and that the outlook for the future is troubling.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (an international group of climatologists), the earth has already warmed one degree in recent decades. They say the reason is an excess of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the result of more people burning more and more fossil fuels.

Locally, it’s hard to say what effect, if any, global warming has had. Since it is a theory, nothing can be proven. However, Memphis has experienced hotter summers and milder winters for years now, and local plant life is changing. Some plants that don’t normally thrive here are now thriving, while some native plants aren’t faring as well. These could be temporary changes due to natural weather trends, or they could be human-induced, permanent changes resulting from global warming.

If it is indeed global warming, and the ice caps continue to melt, Memphis will experience more than just a great view of the ocean: Think overcrowding from migrating populations, crop failures, and increases in mosquitoes and disease. That scenario is admittedly a long way off, but scientists say the time to deal with the problem is now.

The Day After Tomorrow

On December 8, 1917, Memphis received more than eight inches of snow and ice. Hundreds of downtown workers were stranded in their offices. Taxis charged inflated rates to take people home. Temperatures in Memphis stayed below freezing through Christmas, and then a blizzard slammed the city in January, dropping another five inches of snow and sleet. The temperature fell to eight degrees below zero. The Mississippi River froze completely over. Steamers like the Georgia Lee and DeSoto were trapped in river ice. The Daily Appeal reported that some locals took to the frozen river on ice skates.

Eighty-year-old Memphian Jack Phillips remembers times like these.

“It wasn’t a strange sight in those days to see huge chunks of ice coming down the river. You don’t see that anymore,” says Phillips, a Native American who grew up in the city. “At Overton Park, people would go to the pond by the hundreds to ice-skate every year.”

These days, such memories seem worlds away. Memphis hasn’t seen many blizzards in recent decades, and Rainbow Lake doesn’t get ice skaters anymore.

But whether these changes are related to global warming is hard to say.

“It comes down to a difference between weather and climate,” explains Lensyl Urbano, an assistant professor of earth sciences at the U of M. “Weather is what you see every day. Climate is the average that happens over a period of time. So it’s difficult to say with any confidence at all if [recent weather patterns] are affected by global warming. You need a longtime record.”

By longtime record, Urbano means hundreds of years of data, and that simply isn’t there. So instead of studying weather patterns, scientists look to the direct correlation between increasing temperatures and the rising levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere since the industrial revolution.

On a local level, climate change isn’t easy to see, but there are some indicators that it may be happening. At the Memphis Botanic Garden, horticulturist Rick Pudwell says some trees are beginning to leaf earlier in the year.

“At first blush, that doesn’t seem like a problem, but if certain plants leaf out too early and then we get a cold front, it causes the flower buds to freeze and sometimes the leaf buds as well,” says Pudwell.

But while some native plants are suffering, new plants are thriving. Camelias traditionally haven’t fared well in Memphis because the weather is too cold. These days, Pudwell says, they flourish. Same goes for the Japanese Loquat tree. Planting zones are also beginning to fluctuate.

“We’re in Zone Seven, and I see plants that are normally only hearty in Zone Eight areas like Jackson, Mississippi, or Zone Nine, which is the Gulf Coast,” says Pudwell. “Five or six years ago, this wasn’t the case.”

Pudwell says he has also noticed a decline in the number of songbirds in the region. He believes they’re moving farther north due to rising temperatures in the South. This is bad news for gardeners, who see the birds as allies in insect control.

According to Batholomew, with planting zones shifting north, American farm staples such as wheat could become Canadian staples. Urbano says sugar maple trees in New England may also eventually thrive only in Canada if warming trends continue.

According to John Corbett, a retired geography professor from the U of M, these changes could be sparked by only a slight change in the temperature of the oceans.

“The Memphis area would become more humid,” said Corbett. “We’d have more storms and more frequent flooding. If it’s more humid, we’d have more termites, and the wood would start rotting more. The area would start to favor little things you wouldn’t want it to favor, like mold.”

On a worldwide scale, Corbett projects mass migrations due to crop failures and more wars as fossil fuel supplies decrease. As ocean temperatures rise, Corbett says, the world can expect stronger hurricanes. These changes, he says, are mostly human-induced.

“We’re cutting down the rain forests. We’re using more and more fuel,” says Corbett. “The cities are more crowded. We’re destroying animal habitats. The real problem is us — humans.”

Global Warming for Dummies

In a greenhouse, thin sheets of glass protect sensitive plants from cold and frost. But that glass also allows solar energy to come through, where it is absorbed by the plants and the ground inside. The glass traps the heat, similar to a parked car left out in the sun with the windows rolled up.

Carbon dioxide, water vapor, methane, and nitrous oxide are gases in the earth’s atmosphere. They operate much like greenhouse glass. The sun’s energy penetrates the gases, which trap the solar energy. That heat keeps the earth warm and habitable. If it weren’t for the greenhouse effect, the earth would be 60 degrees cooler.

So the greenhouse effect is a good thing. However, the rise of industry, especially in the past hundred or so years, has led to increased burning of fossil fuels that contain carbon dioxide. From the coal burned to fuel power plants to the petroleum burned by cars, each year over the past century, more and more CO2 has been released into the atmosphere.

“Carbon dioxide is a minor gas in the air,” explains Corbett. “[The air] is mostly oxygen and nitrogen. But carbon dioxide is called a greenhouse gas because it has more ability to do what that glass in the greenhouse does.”

Climatologist Charles Keeling has been recording carbon dioxide concentrations in the air above Mt. Mauna Loa in Hawaii since the 1950s. His findings through 2005 show that the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere has risen every year since his study began.

While the earth has natural cycles of warming and cooling, global-warming-theory proponents say the earth is heating up at a faster rate than what should occur naturally.

“The temperature of the earth has already risen about one degree Celsius over the last 100 years,” says Urbano. “In the next 100 years, it could be one or two or even four or five degrees higher.”

One degree may not sound like much, but 100 years isn’t long in the grand scheme of things.

“The temperature difference between now and the last glacial maximum about 20,000 years ago is 10 to 12 degrees Celsius. Back then, the glaciers came all the way down to [where] New York City [is now],” says Urbano.

According to Hsing-te Kung, a U of M geology professor, we may not have enough data to determine if global warming is happening, but he points out that some very old data does exist in the form of core samples climatologists have taken from glaciers in the Arctic region.

“The earth has been around for about 5.6 billion years, and the universe may be 50 billion years old,” says Kung. “Human life is only 10,000 to 15,000 years old. So to really understand climate change, that’s going to be a real challenge.”

The Politics of Warming

In December 1997, a climate-change control treaty known as the Kyoto Protocol was negotiated in Japan. Countries that signed on to the agreement pledged to reduce collective emissions of greenhouse gas by 5.2 percent compared to the emissions from 1990.

As of April of this year, 163 countries have signed the agreement. Australia, Monaco, Liechtenstein, and the U.S. have not. In July 1997, the U.S. Senate unanimously passed a resolution stating that agreeing to such terms “would result in serious harm to the economy of the United States.”

“By not signing the Kyoto [Protocol], the administration has postponed any change in our production of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere for another eight years,” says Barthlomew. “Another administration may do something different, but since this one has chosen to delay that, we’ll pay the price.”

It could be a dangerous decision, considering that the U.S. is one of the largest polluters of the atmosphere. According to Bartholomew, about 80 percent of the fossil fuel consumption in the world comes from the U.S., Europe, and Japan.

He points out that while Europe and Japan may be major contributors to pollution, they’re doing more to effect change.

“They drive more fuel-efficient cars. In Europe, you have to hold the shower nozzle for it to stay on, so you’re not wasting water as the shower runs,” says Bartholomew.

“If we wait until all the other countries of the world produce as much emissions as we do, we’re in big trouble,” says Bartholomew. “You won’t have to worry about the sea level coming up from global warming, because you won’t be able to see [because of] all the smog.”

The White House has come under criticism from environmentalists for downplaying the potential link between global warming and human activity. President Bush dismissed a 2002 report by the Environmental Protection Agency that stated human activity is playing a hand in climate change.

The New York Times reported that Philip Cooney, a former White House official and former oil-industry advocate, altered 2002 and 2003 EPA reports on climate research to downplay the link between emissions and global warming.

Much of the propaganda against climate change is funded by Lee Raymond, the recently retired CEO of ExxonMobil. Rolling Stone reported that since 2000, Raymond has donated $8 million to “right-wing think-tanks that ridicule climate change in the mainstream media.”

“When you look at the naysayers, you need to look at what kind of grants they’re operating on,” says Clark Buchner, the chair of Tennessee Sierra Club’s Global Warming Committee. “Exxon has been one of the most egregious groups about not wanting information on global warming to reach the public.”

In the end, it comes down to economics. Bartholomew points out that the U.S. economy is very complex; any change the U.S. institutes would have a ripple effect economically. But dramatic economic changes may be a sacrifice the U.S. will eventually have to make.

“We’ve got to get the politicians in this country to realize what the hell they’re doing,” says Phillips.

Baby Steps

Since the U.S. government isn’t doing much at this point, what can ordinary people do? And will it make a difference?

These are the questions on the minds of environmentalists like the Sierra Club’s Buchner. His job is to educate the public on the little things that add up to big change. He says the club is currently studying its overall energy policy so they can better inform the public.

“We don’t want to look like alarmist fools,” says Buchner. “In the movie The Day After Tomorrow, 100-foot waves hit New York. Places were icing over in five minutes. That was pretty extreme. But on the other hand, when you have a hurricane like Katrina, that’s extreme, too. Extremes do play out but not necessarily in a Hollywood special-effects manner.”

One of the things the club is looking at is the effect of planting more trees, which absorb carbon from the atmosphere. Other considerations include encouraging power plants to switch to treated coal that emits less carbon dioxide, supporting wind power, and lobbying for corporate standards to reduce vehicle emissions.

One obvious change that drivers can make is to switch to hybrid fuels or more fuel-efficient vehicles.

“There are a lot of things that could be done, but the fact is, we have a society that has fostered, over the last 20 years, the use of SUVs,” says Bartholomew. “Some people buy them for safety, but they waste a lot of fuel. Most people don’t need a vehicle that size.”

Bartholomew says making homes more energy-efficient will also help. Since carbon dioxide emissions are generated by power plants, reducing electrical use can help reduce emmissions. He also suggests using items longer. “The idea of recycling is not just putting things in the recycle bin,” says Bartholomew. “Using cars or cell phones until they are worn out is an important part of reducing carbon emissions. We can’t produce anything new without burning fuel of some kind.”

Locally, Shelby County government has taken several steps that could have an impact on reducing carbon dioxide emissions. The county was designated a “non-attainment” area for poor air quality by the Environmental Protection Agency in 2004.

Last week, county air-quality coordinator Ronné Atkins announced several projects intended to improve air quality. Atkins said some county fleet-services vehicles will be switched to biodiesel, a blend of petroleum and soybean oil that is believed to reduce emissions. And MATA will test the fuel on 25 of its paratransit vehicles. If results are positive, the county may switch more vehicles to biodiesel.

County school buses will soon be retrofitted with special mufflers and emissions filtration systems. And the existing local RideShare program, a free car-pool organization that pairs commuters, has been revamped to be more efficient.

Buchner says the key is making people understand that while the effects of global warming may not affect them in a large way, it may have a huge impact on future generations. “There’s a real difficulty with thinking about doing anything on a long-range basis,” he says. “Unless there’s a threat right in front of them, you can’t get people’s attention.”

According to Urbano, we may not see the effect from changes that are made in our lifetime. But that doesn’t mean they won’t make a difference.

“Assuming we cut off [producing] all carbon dioxide tomorrow, it could still take a couple hundred years for the level of CO2 in the atmosphere to return to where it was before. No matter what we do, some degree of warming is going to be with us,” says Urbano.

It comes down to adopting a new worldview.

“We have to take care of this world because it doesn’t belong to us,” says Phillips. “That’s what Native Americans have been trying to tell everybody since Christopher Columbus first came. We are just the keepers of the earth, and when we leave here, we have to leave it in the condition we found it.”

If more people thought like Phillips, global warming probably wouldn’t be a problem. But until they do, generations to come may be at risk.

Let’s hope future Memphians have plenty of beach towels.

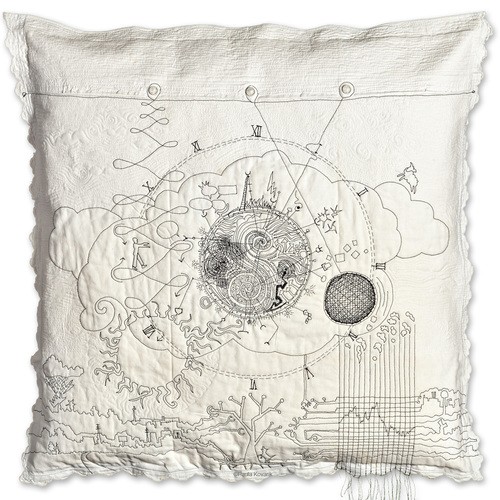

Paula Kovarik

Paula Kovarik  Paula Kovarik

Paula Kovarik  Paula Kovarik

Paula Kovarik