Interstellar (2014; dir. Christopher Nolan)— Christopher Nolan is the dour, pedantic, ambitious, massively successful moviemaker we apparently deserve. He hasn’t made a really great film since Memento came out 15 years ago, but he’s always made sort of interesting ones, and take it from me: his Batman trilogy assumes a lofty, morose grandeur when you watch all three movies in one sitting. And like Quentin Tarantino, Nolan loves film as a medium; he is one of the only filmmakers around who could convince a studio to release prints of his latest work on 70-millimeter film stock. The chance to see a cosmic opera in the double-wide 70mm format got me out of the house on New Year’s Day, and for the most part Interstellar was like other recent Nolan films—complicated, exciting, scientifically sound for the most part, and a little hollow.

But it looked fantastic, and looks count for a lot in a big-budget SF movie. I made some peace with digital projection when David Fincher’s Zodiac came out in 2007; after a while, DCP exhibition, like high-definition television, started to look and feel natural and normal. But as it turns out, film—especially 70mm film—is still markedly superior to the highest-quality digital projection. There’s a wider range of colors available (the blacks, whites and greens are especially fine here) and a more palpable sense of air and space around the actors. Plus, the barely-audible whirr of the projector is as comforting as sitting next to a sleeping dog.

As befits a movie about an uncertain future, Interstellar’s numerous meditations on time, change and decay are its most salient features. At the same time, though, Nolan forges his pop spectacle without ever cracking a smile; he almost seems to be begging someone to laugh in his face. So I’m looking forward to the Interstellar/Boyhood YouTube mash-up where a sobbing Matthew McConaughey watches from outer space as he watches footage of Ellar Coltrane growing up. Grade: B+

Coherence (2014; dir. James Ward Byrkit)—This intelligent, economical and deeply creepy found-footage project stars Xander from Buffy The Vampire Slayer, the winner of the 1982 Miss America pageant, and a half-dozen more not-quite-handsome and just-past-pretty faces you swear you’ve seen before. Although it made less than $70,000 during its brief theatrical run, The Dissolve’s omnivorous, finicky film critic Mike D’Angelo named it his second-favorite film of the year. The man has good taste. Coherence is a near-great film with a great gimmick, and its extended group improvisations are balanced and shaped through Byrkit’s considerable formal and conceptual sophistication. The film’s twists are its reason for existence, so the less you know about them, the more enjoyable it will be. But the numerous shocks and complications eventually frame a key existential question: who do I want to be? Coherence resembles writer-director Shane Carruth’s opaque, highly-organized head-scratchers (Primer, Upstream Color), but Luis Bunuel’s The Exterminating Angel, about a group of dinner guests who discover they can’t leave the house, is an apt comparison as well. It gets under the skin, and just like the 2014 NFC Championship Game, it gave me nightmares that made me doubt my own reality on multiple occasions. Grade: A-

Gone Girl (2014; dir. David Fincher)—Before I had seen Gone Girl, my top ten films of 2014 looked something like this:

1. Only Lovers Left Alive

2. Adieu Au Langage*

2.Get On Up

3.The Lego Movie

4. Ida

5.Tim’s Vermeer

6. Kumiko, The Treasure Hunter

7. Citizenfour

8. Night Moves*

9.The Homesman

10. Force Majeure*

*did not play in Memphis in 2014

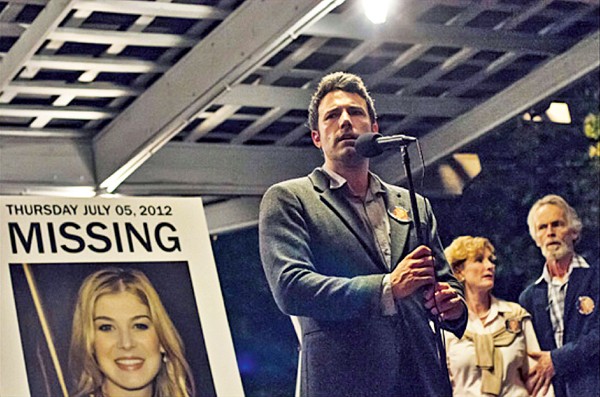

Seeing Gone Girl didn’t change that list one bit; in fact, I don’t think Gone Girl would crack my top 30 or 40 films of year. Gillian Flynn’s wild and clever best-selling novel seemed just bad enough to make a good movie; it’s high-quality trash with some surprising twists and some evocative descriptions of the glory days of paid journalists thrown in for local color and nostalgia. And both Flynn (who wrote the screenplay) and director David Fincher should be commended for taking a different angle to the material: book and movie are two separate entities with two separate agendas. But turning a kinky modern film noir with a crazy femme fatale into a dark meditation on contemporary marriage is a bit much. This movie doesn’t have much to say. Nevertheless, there’s an image for the time capsule here among the underlit greyish-brown murk: a cat looking out the window at the lights of the paparazzi and the police. Grade: B-

Inherent Vice (2014; dir. Paul Thomas Anderson)—Hmmmm…it must be Second Opinion month here at the film journal. But wait, I have something to add to Chris’s comments in last week’s review! So, the stupendous thing about Anderson’s new film is not simply that it’s a relatively faithful adaptation of this particular Pynchon novel; it’s a fairly accurate rendering of what it’s like to read any given Pynchon novel. And since nobody’s likely to turn V, Gravity’s Rainbow, Mason & Dixon or Against The Day into movies, this is probably the only time a Pynchon novel will make it to the big screen in any form. The most unlikely ingredients fare just fine here: the goofy character names; the numerous implicit and explicit hints at dark sexual perversities lurking behind every desk or under every countertop; the vast inland empire of conspiracies great and small; and, most importantly, the sudden whispered flashes of vulnerability and sorrow that emanate from major and minor characters like heat lightning on the horizon. Much occurs in the film, but as Pynchon wrote, “certain things, it is made clear, will not be spoken aloud; certain events will not be shown onstage; though it is difficult to imagine, given the excesses of the preceding acts, what these things could possibly be.” And while we’re quoting some Pynchon here, let’s hope someone will try to adapt The Crying of Lot 49 some day. Grade: A