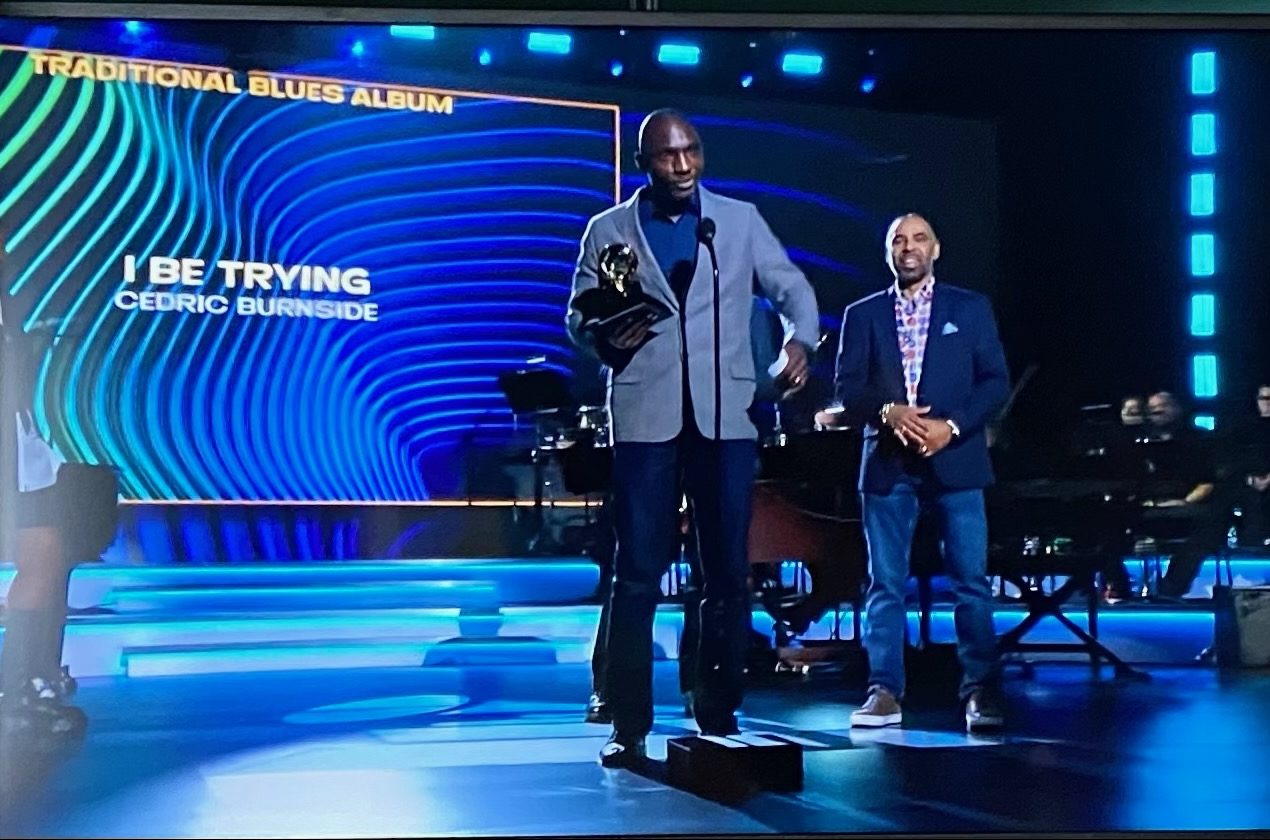

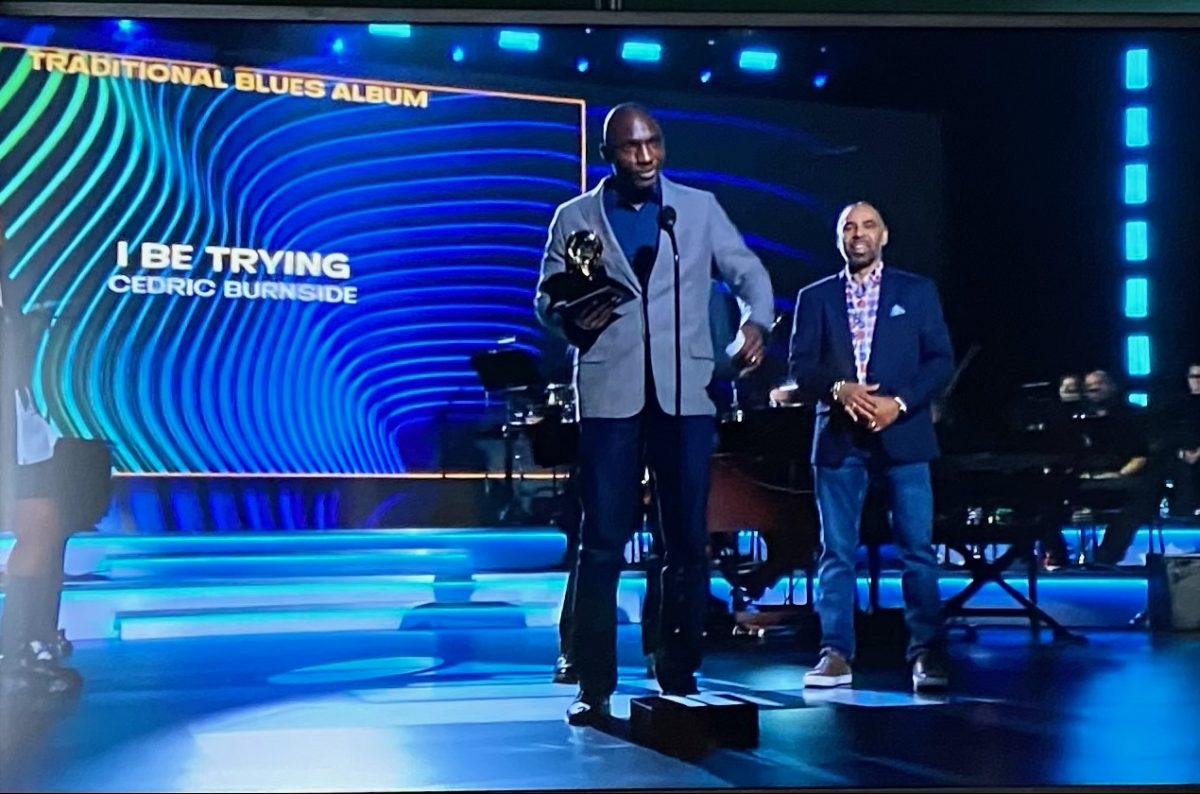

It’s not every day that three different Grammy winners in one year can trace their sound back to one recording studio, but such was the fate that the 64th Annual Grammy Awards bestowed upon Royal Studios this week. While it’s not surprising that Mississippi blues Grammy-winners Cedric Burnside and Christone “Kingfish” Ingram worked at Royal, the studio — and a stellar Memphis musician — also played a key role in recording the debut album by Silk Sonic, whose “Leave the Door Open” claimed four wins: Record of the Year, Song of the Year, Best R&B Performance, and Best R&B Song.

To learn more about this year’s Grammys from a Memphis perspective, I caught up with producer/engineer Boo Mitchell, Royal’s co-owner, on layover in Dallas while flying home from Las Vegas, where the gala event was held on Sunday.

Memphis Flyer: You’ve attended a lot of Grammy Awards ceremonies. Was there anything different this year, even before the winners were announced?

Boo Mitchell: We had a lot of family out this year. My son Uriah was my road warrior with me. We got to Vegas Thursday, and then Jeff Bhasker, the co-producer of “Uptown Funk” and the Uptown Special project, invited us to this insane party. We thought it was in Vegas, but it was in L.A.! So me and Uriah drove to L.A. Friday for this party, and then had to be back in Vegas Saturday morning for the premier screening of Take Me to the River: New Orleans at the House of Blues in Vegas. Then I was invited to the Black Music Collective’s event — the maiden voyage with John Legend, Jay Z and a whole host of amazing artists.

And then we went to see Silk Sonic Saturday. They have a residency at Park MGM. If you’re in Vegas, you should see it. The choreography, the humor, the music, and the musicianship are incredible. Then they have the after party. [Trombonist] Kameron Whalum DJ’s at that, and some of the band hops on stage and plays while Kameron is DJing.

And Kameron’s brother, Kenneth Whalum III, who plays with Nas, was there. I think Kenneth is the one who introduced Kameron and Bruno Mars. Kenneth was playing with Maxwell at the time, or Jay Z. Bruno was just starting to emerge, and was like, ‘I need a horn section.’ So Kenneth connected those dots. It’s a family affair, full circle. And those same guys have been playing with Bruno since the beginning. They’re on Bruno’s early records. Kameron’s been with Bruno’s touring band for ten years.

And you know Kameron, he was playing Three 6 Mafia and Young Dolph and all that stuff. Memphis was in the house!

It seems Silk Sonic is tied to Memphis in more ways than one. You engineered most of the album, yet, because the single was a live recording, Royal wasn’t technically involved in Silk Sonic’s Grammys, correct?

We didn’t get credit for the Silk Sonic single because of a record company glitch. I recorded the intro to the song with Bootsy [Collins], which was supposed to be part of the song, but when it got uploaded, the intro was listed as a separate track.

How many tracks from that album did you work on Royal?

I think seven out of ten tracks, including that intro and “777,” the song they performed at the Grammys. We did the horns on that one with Kameron, Marc Franklin and Kirk Smothers.

Christone “Kingfish” Ingram’s 662 won Best Contemporary Blues Album, and though most of that was engineered by Zach Allen, you engineered the bonus track at Royal.

Man, that kid … well, he’s not a kid anymore. But, he’s literally one of the most talented and prolific guitar players of our time. He plays with the feel of an 80-year-old man. How can you have that much soul? You’re only 20-somethin’!? Kingfish is incredible. His voice, too. I’ve watched him grow as an artist, working with him over the years. And he just keeps getting better and better. That 662 album is amazing. The producer, Tom Hambridge, is a veteran blues producer who worked with Buddy Guy. Pop [Willie Mitchell] and I got to work with Tom on a Buddy Guy record. We did some horns on that album. And Tom did a phenomenal job with Kingfish.

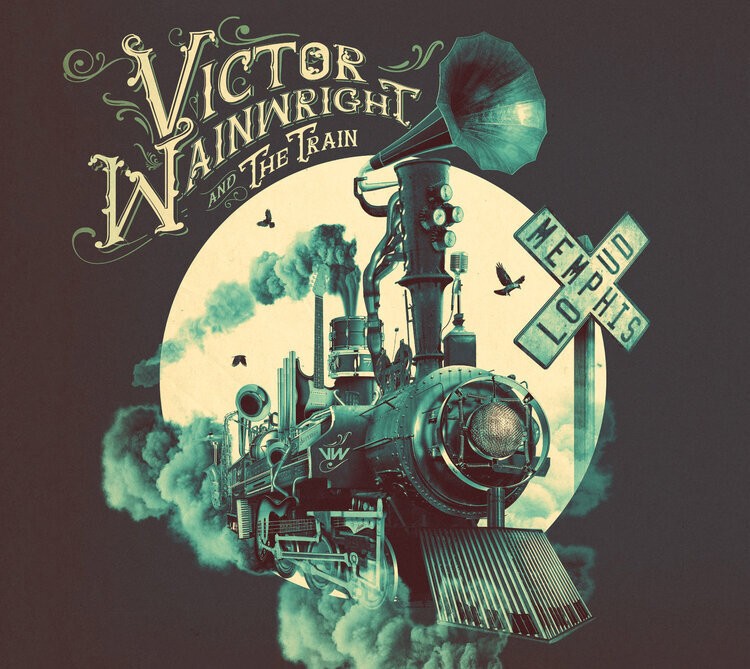

And clearly Cedric Burnside winning Best Traditional Blues Album was very meaningful to you, as producer.

Man, that record, I Be Trying, was so special to me. I’d been wanting to work with Cedric for years. Our chemistry is really good. We’ve always had this instant kinship, and working with him in the studio was like we were raised from kids or something. It was very intuitive. His voice, his musicianship. He’s like the spirit of Mississippi. It’s nostalgic and futuristic at the same time.

Have you known Cedric a long time?

I’ve always known the Burnside family legacy. Maybe the first time I met Cedric was 2010 or ’11, and it may have been a Grammy thing. And I got to make a record with him for Beale Street Caravan. They were doing these videos of different artists at different locations, and they asked me if I would record Cedric in front of a little audience, and film it. Like in a little club. So we did this recording, and it was not the ideal studio setting to make a record. He had a floor monitor — it was more like a club. And I was like, ‘I don’t even understand why this sounds so good.’ Because it was recorded all wrong, according to textbooks. But his energy, man. Sometimes it doesn’t matter how you record things, as long as you capture the energy. As long as God is in the room and you’re recording, and the tape’s rolling. There was clearly something anomalous about it, and about him and his voice. And he was like, ‘Man, that sounds so good!’ I was like, ‘Yeah, right? I don’t know why!’

That may have been the catalyst, because every time I’d see him after that, I’d be like, ‘Man, we’ve got to make a record.’ And then the stars lined up with the label, Single Lock. Those guys are amazing. They just gave me the freedom to do what I wanted to do.

Cedric was so good to trust me. Sometimes I would have these crazy ideas for a blues record. Like, ‘Can we put a cello on this?’ [laughs]. But Cedric really trusted me in the process. Even if he didn’t quite understand what I was going for at the time. And then he’d be like, ‘Man, I had no idea this would sound like that.’ Between the artist and the producer, there’s always a give and take, and I’m not a heavy handed person. I always try to consider what the artist wants or what the label wants. But at the end of the day, I’ll always go with my gut.

Also, Cedric’s songwriting is incredible. That’s one of those albums where something is guaranteed to resonate with you. Even the last song, “Love You Forever,” I was like, ‘Man, we just made a bedroom blues song!’ [laughs]. A blues love song! It’s one of my favorite songs. It almost sounds like something D’Angelo could have sung.

It’s nostalgic and futuristic at the same time. It captures all the spookiness of the old deep blues, and it still sounds current. Some of those tracks could be in a Wu-Tang sample.

And for me personally, Cedric’s record was the first time I got to do what Pop did. Because he produced, engineered and mixed all the Al Green stuff. So I finally got me one, doing it like him. Which is all I want to be anyway.

Kim Welsh

Kim Welsh  Catherine Elizabeth Patton

Catherine Elizabeth Patton