Tennessee officials are devising the state’s first-ever climate action plan thanks to federal funds through the Inflation Reduction Act.

So far, 33 states have created and released climate plans, according to Climate Central, a nonpartisan nonprofit dedicated to reporting on the changing climate. Tennessee’s big-four cities — Memphis, Nashville, Knoxville, and Chattanooga — all have individual plans.

The Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC) is now working with groups across the state for a greenhouse gas emission reduction plan, called the Tennessee Volunteer Emission Reduction Strategy (TVERS).

The “volunteer” part of the name is more than a reference to the Volunteer State, one of Tennessee’s nicknames. The planning approach so far does not seem to favor any mandates to curb climate change.

”Through TVERS, TDEC is focusing on voluntary or incentive-based activities that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and other air pollutants,” reads a website for the plan. “While other states have imposed mandates to reduce emissions, we hope to reach established goals through voluntary measures that may differ throughout the state.”

TDEC won $3 million grant from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in July to develop the statewide climate action plan. Nashville, Memphis, and Knoxville each received $1 million to develop further plans.

The state owes the EPA a draft of a greenhouse gas inventory by the beginning of next month, according to state documents. Tennessee has never published (and has maybe never conducted) an inventory of its greenhouse gas emissions.

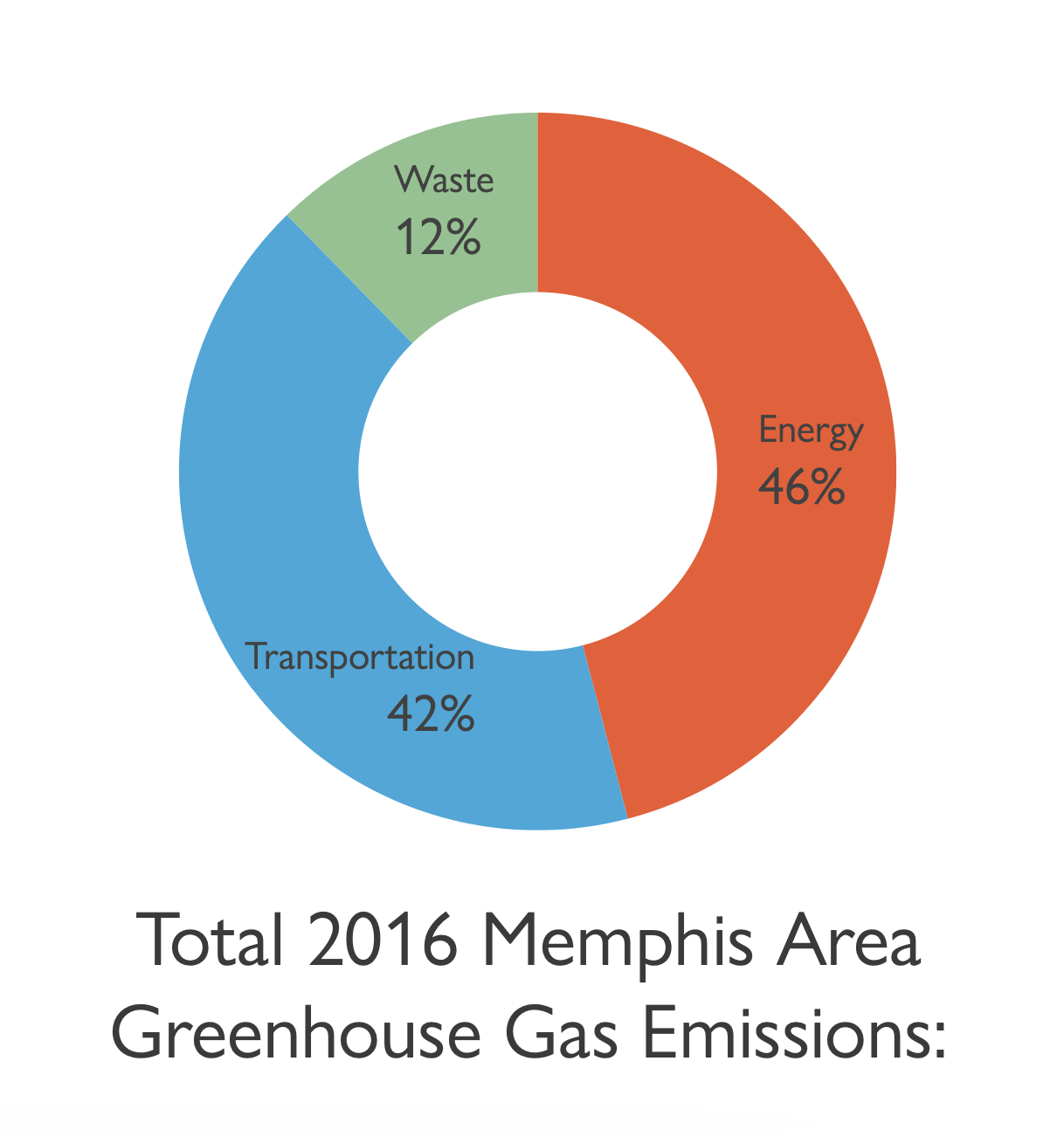

When Memphis officials measured the city’s greenhouse gases for its climate action plan in 2016, they found emissions here came from three major sectors: energy, transportation, and waste.

Energy emissions were 46 percent of the total. The figure includes emissions from energy used in residential, commercial/institutional, and industrial buildings. Transportation emissions (42 percent) included passenger, freight, on-road and off-road vehicles. Waste emissions (12 percent) included solid waste disposal in landfills and wastewater treatment processes.

The total greenhouse gas output that year here was about 17.2 million metric tons of carbon dioxide. An EPA calculator says that amount of emissions is equal to more than 44 million miles driven by gas-powered cars, more than 94,000 railcars worth of coal burned, and more than 2 trillion smartphones charged. The Memphis climate plan said “emissions are fairly comparable to, and even lower than, several other peer cities, including Nashville, Atlanta, Louisville, and St. Louis.”

After turning in a cursory greenhouse gas emissions inventory, the state will then owe the EPA a draft climate action plan by March. Then, officials will have to turn over a comprehensive climate action plan.

The process mandates states to provide greenhouse gas emission reduction measures. These could include “transitioning to low-or zero-emission vehicles, reducing carbon intensity of fuels, and expanding transportation options (biking, walking, public transit).” For buildings, these could include “increasing energy efficiency through incentive programs, weatherization retrofits, building codes and standards, and increasing electrification.”

Climate change has been a particularly thorny political issue in Tennessee with the state’s GOP-dominated legislature. This year, the General Assembly legally defined natural gas as “clean energy,” fought building codes that would reduce electricity consumption, and blocked a weather infrastructure project that would have given real-time data in every county.

In 2019, Gov. Bill Lee said he was was undecided as to whether climate change was real or not. Tennessee Attorney General Jonathan Skrmetti has battled companies on climate change issues throughout his tenure. But at least one Tennessee state government official was frank about climate issues during a presentation on the TVERS plan last month.

“Reducing emissions will result in cleaner air and improve public health,” said Jennifer Tribble, director of TDEC’s Office of Policy and Planning. “Greenhouse gas emissions are also contributing to the warming of our climate and an increase in number and severity of extreme weather events, such as drought, forest fires and hurricanes. These effects have important consequences on human health, such as exposure to extreme heat. Reducing these emissions will improve our resilience to these impacts in the long-term.”

Ward Archer

Ward Archer