On the morning of December 14, 2012, 20 children and six adult staff members at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newton, Connecticut, lost their lives during one of the deadliest mass shootings in U.S. history. The gunman, 20-year-old Adam Lanza, fatally shot his mother while she slept and subsequently traveled to the elementary school, taking 26 other lives before killing himself.

On that same morning, more than 1,000 miles away, Organized Crime Unit officers Martoiya Lang and William Vrooman traveled to a home on Mendenhall Cove in East Memphis to serve a drug-related search warrant. Shortly after identifying themselves as police officers, they encountered gunfire that left Vrooman wounded and Lang dead.

A 32-year-old mother of four, Lang became the first female Memphis police officer to be killed in the line of duty and another statistic in the city’s gun violence dilemma.

Gloria Suggs, a 13-year MPD veteran and close friend of Lang, was in the process of arranging a Christmas luncheon for the Mt. Moriah Police Precinct when she received word of the shooting.

“It still doesn’t seem real,” Suggs says. “For her life to be taken so tragically at the hands of a gun … it hurts. It hurts so bad to know that someone can take a gun and just point it and shoot, not even thinking about the consequences. Once you use a weapon, you can’t take it back. Guns are not toys. You can’t take them, point and shoot, and think it’s going to be okay, because it’s not.”

The alleged gunman in the shooting is 21-year-old Treveno Campbell. He’s charged with first-degree murder and criminal attempt to commit first-degree murder in the death of Lang and the wounding of Vrooman. Campbell used a stolen 9-mm handgun that held a 16-round magazine.

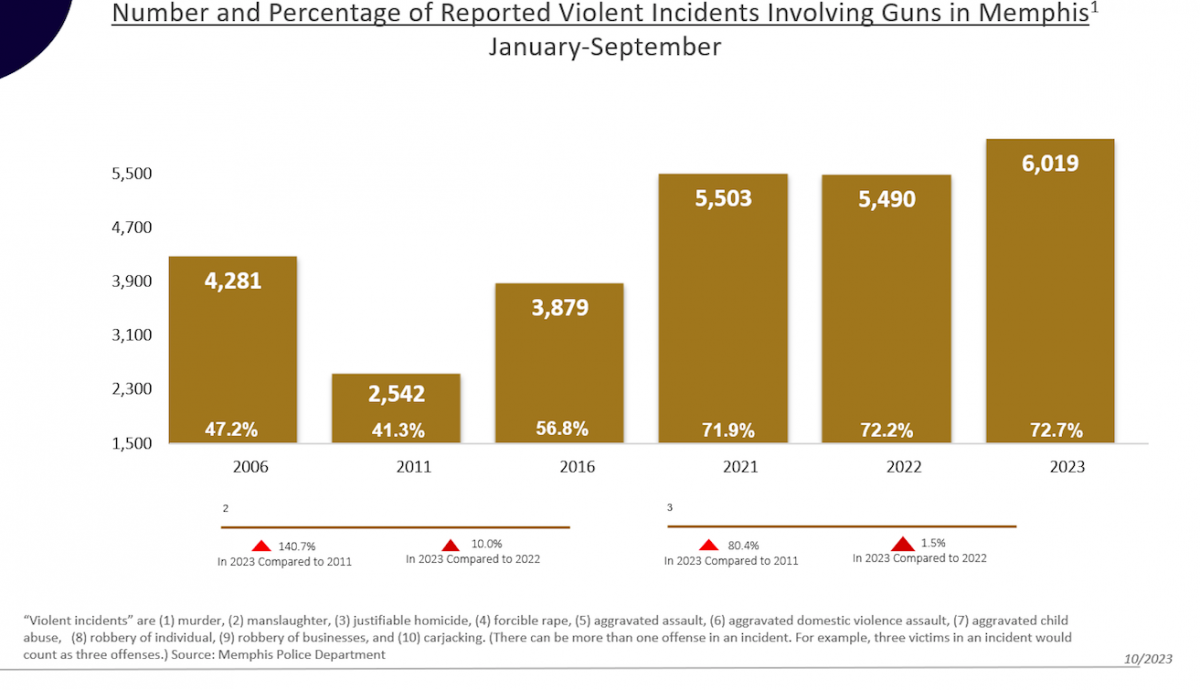

The Lang case is just one of 157 murders — the highest murder rate that Memphis has had since 2008 — that occurred in 2012. More than 80 percent — 127 of them — involved a firearm. Only 17 of those homicides were ruled justifiable, meaning the perpetrator acted in self-defense and was not charged.

Memphis isn’t new to gun violence. Thousands of lives have been lost through the decades due to firearms. The city’s murder rate even received national exposure with the documentary series The First 48, which profiled numerous Memphis homicides over a three-year span.

“Guns seem to be the weapon of choice for the criminal element,” says Memphis Police Department director Toney Armstrong. “I think strict and concise gun laws are needed. There are certainly some gun legislations that need to be handed down. You can’t just look at [the gun violence issue] from a law enforcement [standpoint], because we enforce the laws that are on the books. We arrest people for guns all the time, but if you look at it from a police perspective, there are limitations as to what we can do. It’s a collaborative effort.”

Armstrong says it’s difficult to create a crime initiative that predicts where the next homicide will occur, especially when the people involved are familiar with each other. In 2012, more than 60 percent of homicides involved individuals who knew each other.

Nearly two weeks after Lang’s death, on December 27th, MPD officers fatally shot 32-year-old Charles Livingston, an armed-robbery suspect, after he fled through the woods from a McDonald’s on Frayser Boulevard. Officers said the suspect pointed a gun at them, which led them to discharge their weapons.

On January 11th, an MPD officer fatally shot 67-year-old Donald Moore at his Cordova home. The officer said he shot Moore after he pointed a gun at him and several Memphis Animal Services employees who were there to serve an animal cruelty warrant.

A week later, on January 17th, officers shot and killed 24-year-old Steven Askew as he sat in his car in the parking lot of the Windsor Place Apartments at Knight Arnold and Mendenhall. The officers shot Askew after he allegedly pointed his handgun, which was registered, at them.

On January 23rd, one week after Askew’s death, an MPD officer shot 18-year-old Bo Moore in the parking lot of the Quick & Easy convenience store on South Highland after he pointed a gun at the officer.

The recent rash of officer-involved shootings has led some Memphians to wonder if MPD officers have become trigger-happy since Lang’s death.

Armstrong, however, says his officers are following proper protocol when they’re forced to shoot someone.

“Every shooting that we’ve had recently, there has been a gun recovered,” Armstrong says. “We have to be careful and question the behavior of the suspect rather than question the behavior of the officer. You’re talking about a law enforcement officer who’s commissioned and sworn to uphold peace. We’re questioning his behavior when somebody tries to impede upon that and threaten his or her life.”

It’s not realistic to think that Memphis — or any other major U.S. city — can completely rid itself of gun violence, but are there realistic steps that can be taken to lower the gun-crime rate?

Memphis mayor A C Wharton is among the group of citizens pushing to lower the gun violence rate in the Bluff City. In January, Wharton unveiled “Memphis Gun Down,” formerly known as the “Youth Gun Violence Reduction Plan.” The plan has five core aspects: suppression, community mobilization, youth opportunities, intervention, and organizational change and development.

The core objective of “Memphis Gun Down” is to reduce youth gun violence by 10 percent citywide and 20 percent in selected areas of Frayser and South Memphis by September 2014. It’s one of several initiatives created by the Mayors Innovation Delivery Team, financed by a $4.8 million grant provided by New York mayor Michael Bloomberg to help reduce handgun violence.

“The level of gun violence that we have is totally unacceptable and intolerable,” Wharton says. “It’s affected me personally. I live in the middle of the city, and it’s not at all rare for me to be awakened by gunfire. The threat of gun violence affects us all. There’s not a person in this city who hasn’t been affected personally, although they may have not had a gun pointed at them.”

Wharton says he’s in the process of working with the legislature for passage of a bill that would make it a separate offense to use a stolen gun in the commission of a crime.

Wharton is pushing for laws requiring universal background checks (regardless of where the gun is sold or traded), limiting the size of handgun magazines, higher bail for gun criminals, stiffer sentences for those using stolen guns to commit crimes, and requiring people to report when their firearms are stolen. “When a person steals a gun, they are not stealing it for the sake of going hunting,” Wharton says. “They’re stealing it to sell it, trade it for drugs, or use it in a crime. Folks who have a legitimate need for a gun and wish to obtain a permit to carry it, go to a licensed dealer and buy the gun.”

It’s not just Memphis. Gun violence affects the entire United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. In 2010, more than 31,000 people died from gun violence in the U.S. — 932 of these deaths occurred in Tennessee — and nearly 67,000 were wounded.

In January, President Obama introduced a $500 million proposal to help curb gun violence. The proposal highlights some of the same matters that Wharton touched on — universal background checks for anyone seeking to purchase a gun and bans on military-style assault weapons and high-capacity ammunition magazines. In addition, a school safety initiative includes placing 1,000 police officers in schools and training more health professionals to deal with young people who may be at risk. The plan will also direct the CDC’s research on the causes and prevention of gun violence and require federal law enforcement to trace guns recovered in criminal investigations.

“I support what the president is trying to do,” Wharton says. “I would simply ask that in addition to focusing on what can be done in Washington, let’s do more to empower our local law enforcement agencies, so that they can really get to the crux of the problem, which is in the streets of Memphis and other cities. The federal government should do those things it is uniquely empowered to do, such as dealing with interstate trafficking and stolen guns, creating the national background check system. … States can’t do that.”

A large percentage of gun violence in Memphis, and nationally, is committed with illegally obtained firearms.

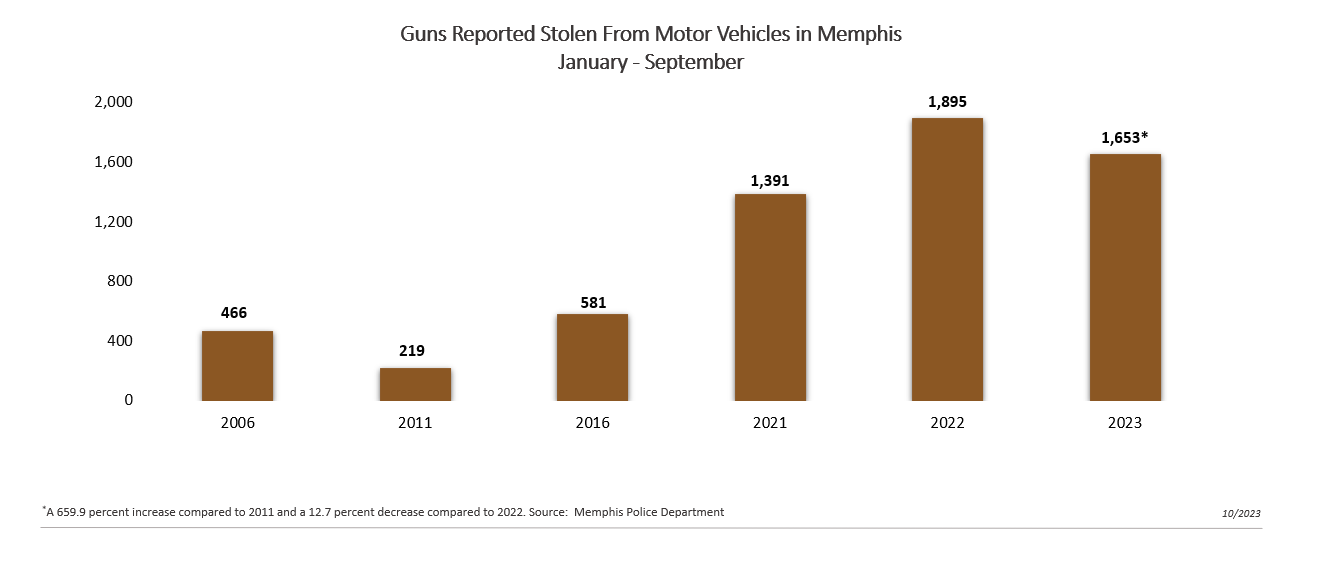

Andrew McClurg, a University of Memphis professor and firearms policy expert, says research reveals that an estimated 600,000 guns are stolen each year in the U.S. He says roughly one-third of all guns used in crime are stolen.

“As a nation, we have fixated on the Sandy Hook Elementary School shootings. But people are getting shot and killed in cities like Memphis literally every day, and most people don’t blink an eye,” McClurg says.

“Gun violence has become so common that we have become numb to it. Mass shootings are rare events, as are attacks with assault weapons. We need to focus regulation efforts on cutting the supply of illegal handguns.”

A typical handgun retails for $300 to $600, according to Classic Arms of Memphis, a gun retailer. However, on the streets, the price tag is often less than half that.

Delvin Lane, a former member of the Gangster Disciples, says it’s possible to purchase firearms on the streets for as little as $25. Lane now leads the 901 B.L.O.C. Squad, a five-man group that’s part of Wharton’s initiative to reduce youth gun violence.

“Gun violence has affected me my entire life,” Lane says. “I lost my best friend to gun violence at age 12; my brother is serving life in prison; and I have lost my play brother to gun violence. I can’t count on all my fingers and toes the close loved ones I’ve lost to gun violence.”

Lane almost witnessed another gun death on January 8th, when a 17-year-old was shot in the neck outside an anti-gang-violence meeting the 901 B.L.O.C. Squad was holding at the North Frayser Community Center.

“I’m not sure if it was done to disturb our presence or simply a random act of violence,” Lane says. “But I’m thankful that the youth is okay. We are determined to keep the movement going. We will not be discouraged. We have to take a stand against gun violence.”

In 2012, 1,343 people between the ages of 13 and 24 were arrested for gun-related crimes in Memphis, according to MPD data. That’s 439 more than the 2011 total of 904. People in that age range are responsible for the bulk of the city’s murders.

Bernard Taylor began selling guns as a teen after a co-worker told him about a large quantity of firearms he was looking to get rid of. Taylor began to purchase guns at wholesale prices — everything from 9 millimeters to .45s to Tec-9s — to sell on the street.

“On the street, the price of a gun is much lower, because you don’t know if it came with a ‘body’ [slang to indicate a person has been killed with it] or if they committed a robbery with it,” Taylor says. “I don’t think guns will ever be off the streets. Wherever you go, there’s going to be a gun on the street, because it’s power. I think everybody has the right to bare arms. We need to start investing in more studies on people’s [mental health], because guns don’t kill people. People kill people.”

A significant number of handguns used in crimes comes from residential or car burglaries. Unfortunately, many gun thefts aren’t reported, either because the owner obtained the gun illegally or is worried about potential liability if it’s subsequently misused.

According to Armstrong, gun owners can help lower the number of illegal guns on the streets by securing their own firearms, recording their serial numbers, and reporting when they’re stolen.

Although many gun crimes are committed with illegal or stolen firearms, people who possess registered firearms have perpetrated some of the nation’s most horrific shootings. The firearms Lanza used in the Sandy Hook massacre came from his mother’s collection of registered guns. James Holmes used a registered AR-15 to kill a dozen people and wound 58 others at a screening of The Dark Knight Rises in Aurora. In the 2007 Virginia Tech massacre, 23-year-old Seung-Hui Cho used a registered Glock 9-mm and a .22-caliber pistol to shoot and kill 32 people and wound 17 others.

One of the co-founders (who wanted to remain anonymous) of Don’tShootMemphis.org, a website that disseminates information on the city’s gun violence epidemic and provides strategies on how it can be lowered, is a staunch gun-control advocate.

“There’s no reason for anybody to own an AR-15, unless you want to kill somebody in a hurry,” he says. “There’s no reason to have a clip of more than seven bullets. That’s to shoot people with in a hurry. Or to have armor-piercing bullets, unless you want to be sure that the policeman you shoot is going to die. There’s no reason you wouldn’t have everybody go through a background check, unless you want to be sure you can sell guns to people who don’t have them. Why are we, in the city and county, allowing gun shows to be held in public facilities? We shouldn’t, unless they agree to a full background check.”

The co-founder of Don’tShootMemphis.org believes that the city, and the nation, should adopt a buy-back program, which involves people turning in guns for a monetary reward.

In 1996, Australia had a buyback that took in 600,000 illegal firearms. In 2003, the country had another one, which resulted in the return of 50,000 illegal pistols.

“Nothing’s going to solve the entire problem, but we’ve got to try,” the co-founder of Don’tShootMemphis says. “If any one of these [strategies] saves one life or 20 children from another mass shooting, then we’ve done a good job.”

It may be an overstatement to say Memphis is experiencing a gun epidemic, but the amount of bloodshed caused at the hands of firearms in the city is extensive. For a significant decrease in gun violence to occur, a collaborative effort from the MPD, local government, as well as city residents has to take place.

“We need to seriously address the issue and leave knee-jerk reactions behind,” says Richard Janikowski, a criminology professor at the University of Memphis. “Accept that the availability of firearms significantly contributes to our violence problem and then think through how we can address it within constitutional boundaries. There are many things that can be done that an overwhelming majority of reasonable people can agree upon.”