My family lived in Atlanta in the early Seventies. These were my preschool years, so memories are blurry at best. But it was an extraordinary time in an extraordinary place, largely because of the great Henry Aaron. I’ve been fighting back tears since last Friday when we learned the Hammer had died at the age of 86.

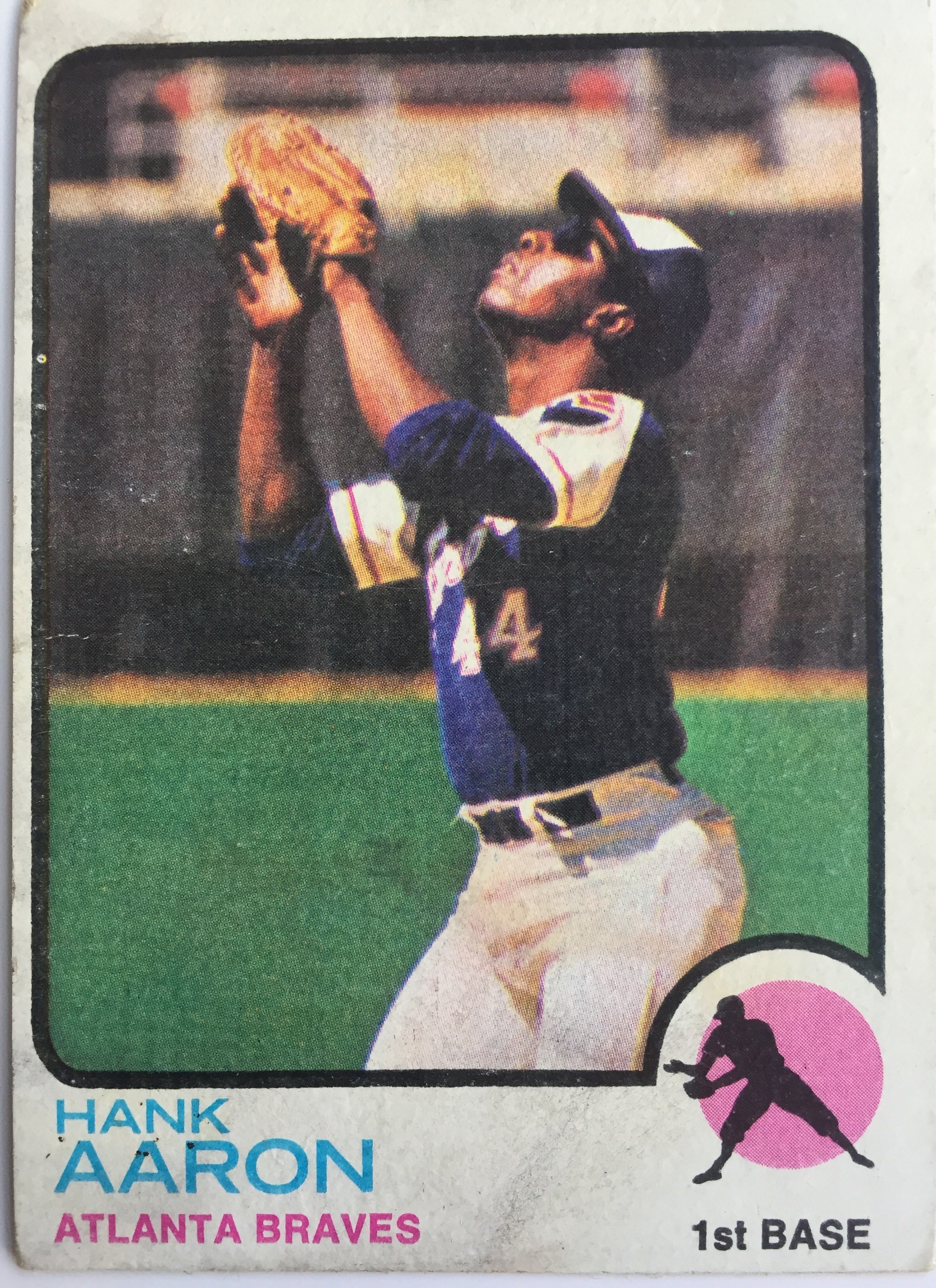

My parents were pursuing doctoral degrees at Emory University, and I was an only child when we arrived in Atlanta late in the summer of 1972. Mine was a St. Louis Cardinals family — Dad born and raised in Memphis — but Atlanta had become a big-league town in 1966 (when the Braves moved from Milwaukee), and we found time for outings to Braves games during the summers of 1973 and ’74. Which means 4-year-old me sat in Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium when the great Henry Aaron took the field for the home team. I was more interested in the Braves’ mascot (and his dances after a home run) than the players actually hitting the baseball, but it’s safe to say I witnessed one or two of Aaron’s 755 career home runs, a record for the sport that stood for more than 30 years.

Aaron’s most famous home run, of course, was his 715th, hit against the Los Angeles Dodgers in Atlanta on April 8, 1974, to break Babe Ruth’s career record. It was the second-biggest highlight of that year for me, as my sister, Liz, was born 10 days earlier. (I do remember leaving my nursery school early, to meet the new arrival.) I’ve seen Aaron’s famous shot hundreds of times, and every time it makes me think of my only sibling. That’s a gift Hank Aaron provided my family without knowing we even existed. Such is the work of legends.

If you need a number to associate with Aaron, make it 6,856, his record for career total bases, and one we can safely say will never be broken. (Stan Musial is second on the chart, but more than 700 total bases — two outstanding seasons — behind Aaron.) Aaron’s career began in the Negro Leagues, even after the major leagues had integrated, so he represents a human bridge to a time when a celebration of baseball’s best meant only partial recognition. He endured hate and racism as he “chased” the record of a revered white icon. (Quote marks because Aaron never targeted Ruth’s mark. He was simply so good that the record became part of his story.) Hank Aaron remained dignified, strong, perceptive, and somehow, gentle through it all. He was a titan of a human being, one who just happened to be very good at baseball.

• The only man to hit more than 755 home runs — Barry Bonds — may be voted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame four days after Aaron’s passing. If Bonds again falls short in his ninth year of eligibility, it’s because there are enough voters (more than 25 percent) still uncomfortable about honoring a man deeply connected with performance-enhancing drugs. And if Bonds joins Aaron in the Hall of Fame? There are records, and there are the men who break them. There is a standard established by the Baseball Hall of Fame, and a standard established by the life of Henry Aaron. Those paying close enough attention recognize a dramatic distinction. Rest in peace, Hammer.