Books about Memphis, the Mid-South, or the South in general. Books by Memphians, Mid-Southerners, or Southerners in general. No time like the present, summer 2014, to take stock of what’s new and what’s in store for readers this season. And not only this July and August. Last week’s Flyer reported on the newly created Mid-South Book Festival, slated for September — a festival that will highlight the record number of writers who make or made Memphis home. In this issue, the Flyer staff takes a look at the latest from local and regional writers and at titles of interest to local readers, so take your pick: fiction and nonfiction; Southern foodways and full-gospel folk art; Memphis politics, Memphis music, and lesser-known Memphis history. We’ll start with some signings this month and move to two titles due in August.

The Booksellers at Laurelwood and Burke’s Book Store certainly do their part to spotlight local writers, and Barnes & Noble at Wolfchase will too this week in its annual salute to Memphis-area authors. On Saturday, July 12th, 2-4 p.m., the store has invited close to a dozen of them to discuss and sign their work. Go to barnesandnoble.com, find the Wolfchase location, and click on “Local Author Panel 2014” for a list of the writers who will be on hand.

Earlier in the week, on Thursday, July 10th, 5:30-6:30 p.m., physically be at Burke’s for a book signing but mentally head for the hills — the hill country of north Mississippi. That’s where you’ll find a university town very like Oxford, and it’s the primary setting for Flying Shoes (Bloomsbury; $26), the debut novel from Lisa Howorth. Howorth’s nonfiction has appeared in Garden & Gun and Oxford American, and 35 years ago, she and husband Richard opened Oxford’s fabled Square Books. But was there ever a hint that Howorth herself would have such a good hand at writing fiction? Flying Shoes is proof Howorth has indeed a sure hand. The story is partially based on the murder decades ago of Howorth’s 9-year-old stepbrother, but despite that grim subplot, this character-driven novel is winning in so many ways. Where to begin counting the ways? With Mary Byrd Thornton, wife of an art-gallery owner, mother of a pair of children perhaps too smart for their own good, best friend to the gay neighbor who’s head of a chicken empire, sometime customer of a sexy but ne’er-do-well drug dealer, and employer of Evagreen, the woman who keeps order in the Thornton household until Evagreen’s own daughter winds up in jail in Memphis for murder. Add in a fine-art photographer not unlike William Eggleston, a semi-homeless Vietnam vet Mary Byrd calls on for odd jobs, and back to Mary Byrd herself — soldiering on with wry humor, a good heart, a well-deserved cocktail or three, and a cigarette now and then.

Now switch gears and head due south of Memphis. You’re going to the dogs. Photographer Maude Schuyler Clay did in her travels through the Mississippi Delta. Readers of Delta Dogs (University Press of Mississippi; $35) can too, and there’s no need to wait for summer’s dog days. Clay will be signing her book at Burke’s on July 17th, but don’t go looking in these pages for pure breeds and leash laws. The dogs Clay captures in black and white are as tied to the landscape as kudzu and farm fields and often free to roam — in packs or standing solitary, loping along, high-tailing it, or sitting nobly as if command of, if not indistinguishable from, the stark landscape.

Want “stark” but in an urban setting? Travel the stretch of Lamar Avenue where Bluff City Pawn does business. Bloomsbury has a real handle on Memphis and parts south this summer, because in addition to Flying Shoes it’s publishing Bluff City Pawn, due the first week of August, by Stephen Schottenfeld. He teaches these days at the University of Rochester, but he once taught at Rhodes, and this debut novel of his is solid storytelling that’s as character-driven as Flying Shoes. Family-driven too: three adult brothers — the oldest: a super-successful developer; the youngest: a semi-dangerous deadbeat; the middle brother: a hard-working pawnshop owner who’s offered a valuable gun collection to sell. That one collection could earn Huddy Marr the money to move his pawnshop from deteriorating Lamar to thriving Summer — and to maybe a better life. Only thing is: Huddy’s older and younger brothers get in on the deal and mess up the works big time. Here’s the deal with Bluff City Pawn: Schottenfeld teaches English, but this novel had me thinking the author’s a cultural anthropologist, because his book is a spot-on depiction of contemporary Memphis, from low end to upper level.

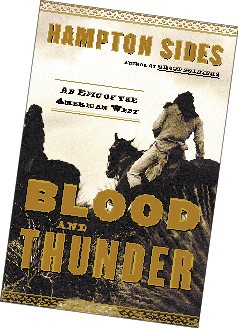

On to the very upper level: the North Pole, which is where Lt. George Washington De Long and his crew thought they were headed in 1879. The expedition was to confirm theories that the Pole was an ice-free open sea. But leave it to native Memphian Hampton Sides — author, most recently, of Hellhound on His Trail — to tell where and how De Long and his crew ended their adventure in In the Kingdom of Ice: The Grand and Terrible Polar Voyage of the USS Jeannette (Doubleday). The book is indeed grand-scale, and the bulk of Sides’ narrative is devoted to De Long and his crew as times get tough, then tougher, then … no reason to spoil it for readers before In the Kingdom of Ice appears the first week of August. No reason, however, not to say this now: Sides’ telling of the resourcefulness these men displayed and the hardships they endured is some of the best writing he’s ever done. — Leonard Gill

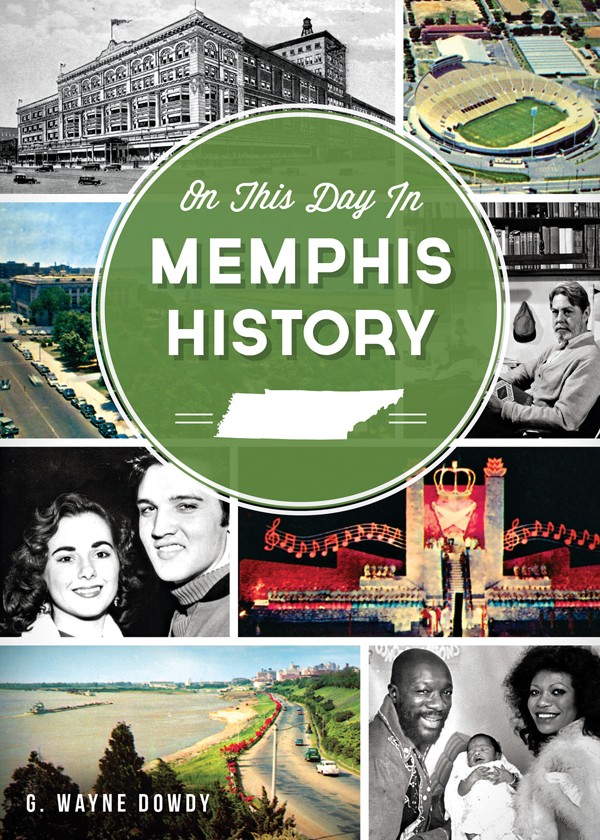

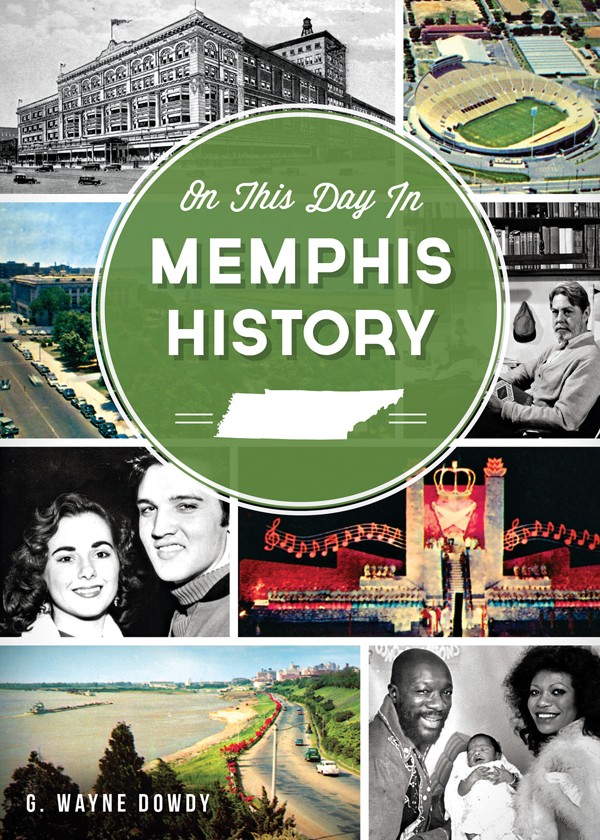

On This Day in Memphis History

By G. Wayne Dowdy

The History Press, 396 pp., $14.99 (paper)

Something of note happens every day in Memphis. And that’s the basis of G. Wayne Dowdy’s book On This Day in Memphis History. The author, manager of the Memphis Public Library and Information Center’s history department, tells 365 of those stories, one for each day of the year.

In the introduction, Dowdy says some Memphis stories — fascinating as they are — just don’t fit into the city’s larger narrative. So he wanted to tell those stories and avoid the big events in the city’s history. “My hope is that most of the daily entries are not known to those who have studied Memphis history or even just lived here for a long period of time,” Dowdy writes.

On This Day in Memphis History begins with a bang — many bangs. Hundreds of Memphians rang in the beginning of 1950 with firecrackers and “sidewalk torpedoes” on Main Street. That New Year’s Eve fell on a Saturday and “spirit was at its highest in Memphis.” Police arrested none of the revelers, save one: John Brown “lost his head” and threw a firecracker at the feet of two police officers.

Among Dowdy’s other findings: African-American street preacher Mary Jones declared on March 27, 1906, that she would sink Memphis into the Mississippi River (in hopes of scaring her wayward husband back home). On May 16, 1919, a grand jury declared Memphis a “lawless town,” criticizing the city’s unwillingness to enforce its own laws. And the Memphis Rogues, the city’s North American Soccer League franchise, notched its first win at Liberty Bowl Stadium on May 20, 1978.

On This Day in Memphis History is filled with great tales that will delight and engross everyone — from the new-to-towner to the hardcore native Mempho-file. But a welcome addition would have been an index in the back of the book to help readers find their favorite topics. — Toby Sells

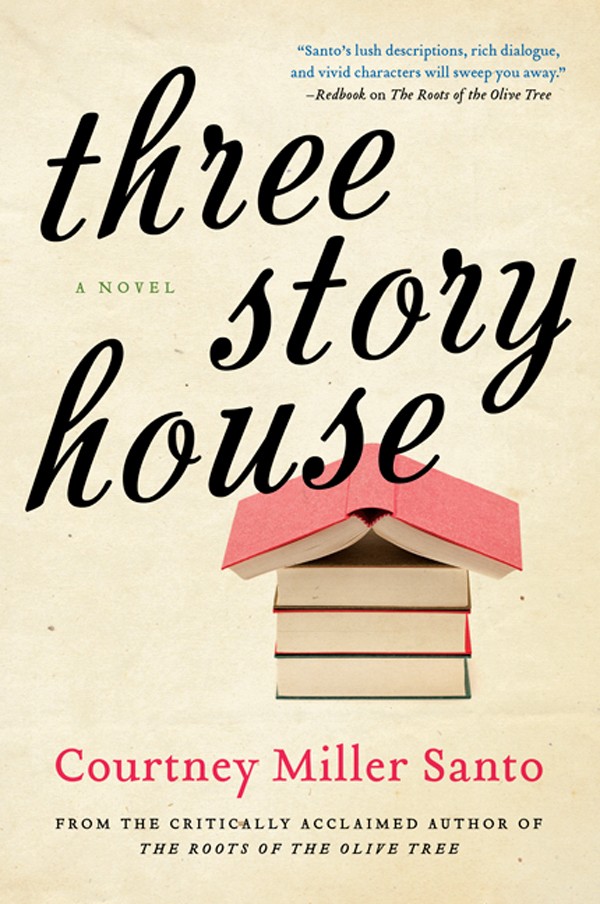

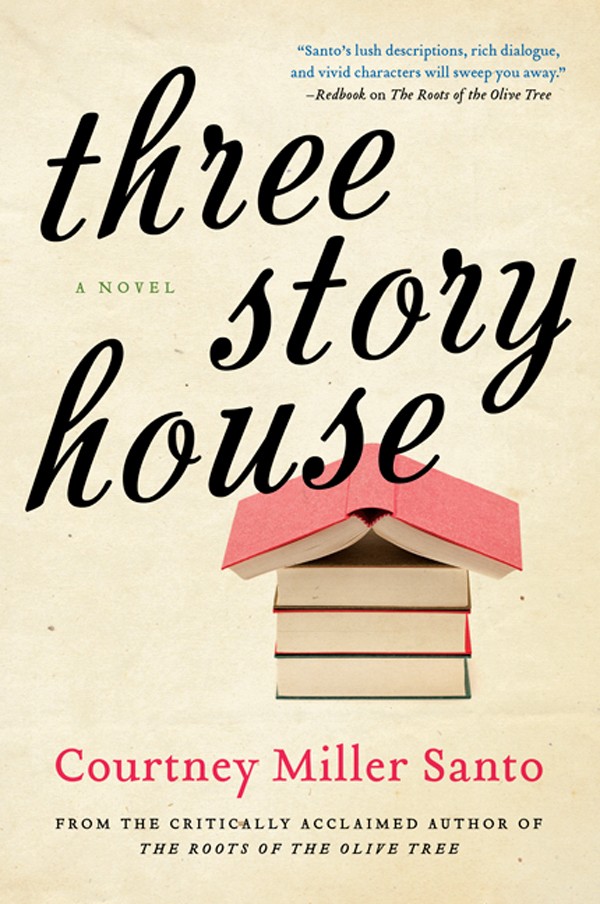

Three Story House

By Courtney Miller Santo

William Morrow, 416 pp., $14.99 (paper)

Later this summer, keep an eye out for the second novel from Courtney Miller Santo, an instructor and administrator in the University of Memphis’ creative writing program. Santo’s interest in familial relationships inspired her California-set, debut novel, The Roots of the Olive Tree, and she continues that theme in her second novel, which brings the drama home to Memphis.

In Three Story House, Santo tells the tale of three cousins (and childhood best friends): Lizzie, Elyse, and Isobel. The book follows the women, now in their late 20s, as they reunite in Memphis to help Lizzie rescue and renovate the historic house where she was raised by her mother and late grandmother. The move to Memphis and renovation project are a last grasp at hope for Lizzie, who feels lost after a knee injury forces a hiatus in her professional soccer career. Meanwhile, Isobel’s acting career in Los Angeles is at a standstill, and Elyse’s life in Boston is marred by unrequited love. So the two decide to move with Lizzie to Memphis to provide emotional support and because “the only way to forget your own problems is to get involved in helping someone else overcome theirs,” according to Elyse.

Three Story House is told in three parts, with each part focusing on one of the cousins’ lives and perspectives. As the women work on the house, which sits on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River, they accidentally unearth some hidden family secrets as well as some wounds of their own, which show that family can be a source of great joy or great pain — and often both. — Hannah Anderson

Courtney Miller Santo will be reading from and signing Three Story House at the Booksellers at Laurelwood on August 19th at 6:30 p.m.

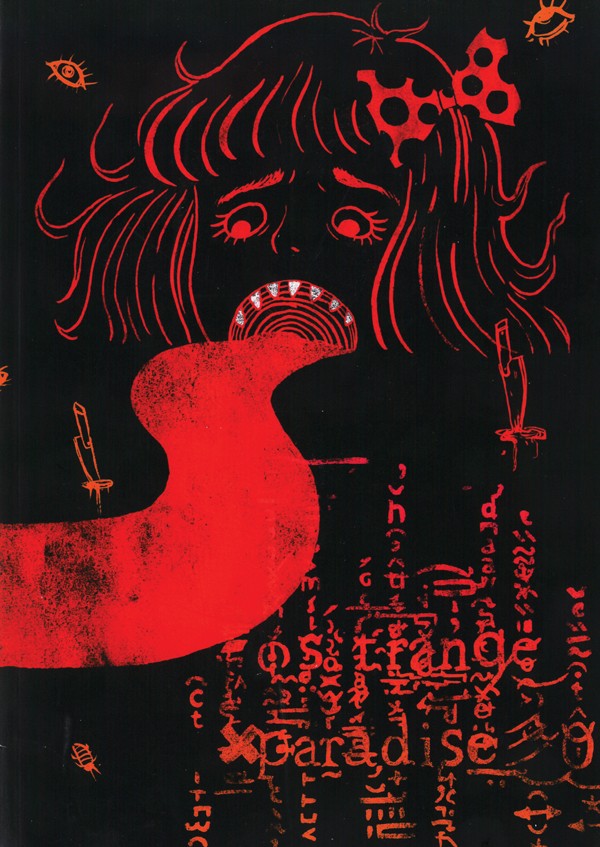

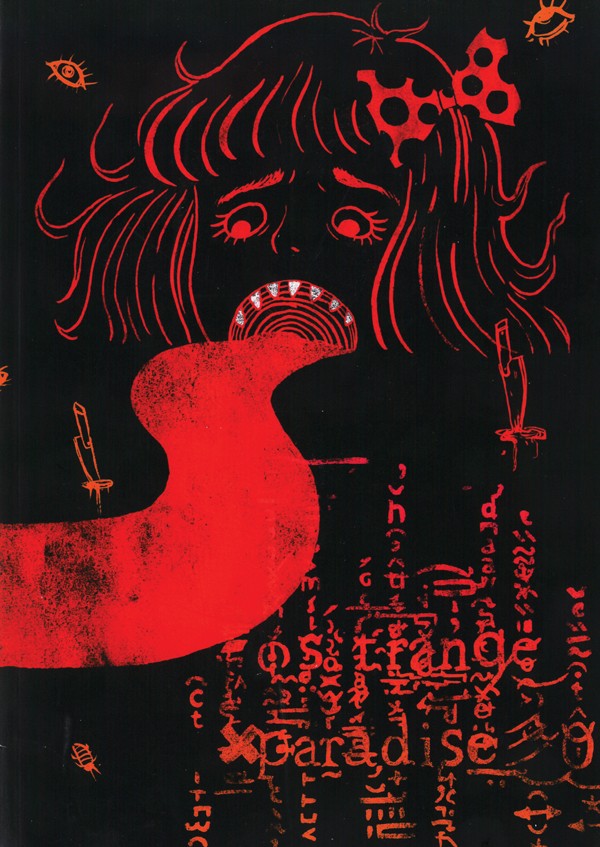

Strange Paradise Issue #1

By Anna Rose and Jenny Zych

54 pp., $20

Strange Paradise Issue #1 is whimsical and freaky, both at the same time — a true tribute to Asian horror. The fanzine may be unsettling to some, but that would be the perfect reaction, because it’s a celebration of all things creepy. Its pages, meticulously illustrated by more than 30 artists, feature an alternative, supernatural universe of mutilated bodies and vampires, while post-surgical mutations grace other pages. Even the cutesier illustrations are bizarre.

Co-editors Anna Rose — who grew up in Memphis, the daughter of Pamela Denney, food editor for Memphis magazine — and Jenny Zych graduated from the School of Visual Arts in New York City last year. It was Zych who came up with the idea for Strange Paradise, according to Rose.

“Jenny and I have been very inspired by the genre of Asian horror films in our own art, so we wanted to give back to something that was dear to us. All contributors were also fans of the genre, and we asked everyone to pick a film that deeply inspires them and create something based off it,” Rose said in an email. “For me, it’s a toss-up between the pacing and the imagery of Asian horror films that I love so much.

“Unlike western horror, Asian films seem to have a slower progression in the plot, so the tension and suspense feels much stronger. There are many reoccurring visual themes I do love as well, such as beautiful, vengeful ghosts or taking normal objects and subverting their everyday appearance to something much more sinister.” — Alexandra Pusateri

To purchase Strange Paradise Issue #1, go to astralrejection.bigcartel.com.

Woman with Guitar: Memphis Minnie’s Blues

By Paul Garon and Beth Garon

City Lights Publishers, 408 pp., $18.95 (paper)

Did you know that the mills of ancient Rome shut down during a festival celebrating the virgin goddess Vesta? Grinding didn’t start with the Memphis Grizzlies or with Prince’s “Darling Nikki” or even as a corollary to the bumps of Gypsy Rose Lee. It’s an ancient sexual idiom dating back at least to Roman satirist Petronius, as Paul and Beth Garon point out in Woman with Guitar: Memphis Minnie’s Blues, a scholarly biography of the pioneering blues singer and player.

The Garons take readers on a short tour of agro-industrial metaphors as an introduction to Minnie’s often covered “What’s the Matter with the Mill,” a song thick with effortless double entendres and bridging traditions between down-home country blues and vaudeville. Muddy Waters performed it regularly. So did country piano player and Jerry Lee Lewis inspiration Moon Mullican. So did Western Swing superstar Bob Wills. As the Garons show again and again, Minnie’s earthy appeal was broad. Her playing was, as described by poet Langston Hughes, like “heartbeats mixed with iron and steel.”

Lizzie Douglas, known to blues fans as Memphis Minnie, lived a colorful life. The hard-drinking guitar player described money as her birthstone, and she liked to play while she worked and to work while she played. Minnie cut more than 200 records in a career that spanned from the 1920s to the 1960s, earning her uncommon respect for her playing and songwriting in a male-dominated industry. Woman with Guitar follows Minnie from rural Mississippi to Beale Street to Chicago and back to Memphis again, documenting the groundbreaking highs and the heartbreaking lows. It also digs deep into her discography, running down threads of protest and cultural commentary.

Originally published in 1992 by City Lights, the new 2014 edition of Woman with Guitar comes with new information regarding Minnie’s disputed birthplace, new images, and an extended discography that includes digital formats. — Chris Davis

To order Woman with Guitar: Memphis Minnie’s Blues directly from the publisher, go to citylights.com.

Orange Mound

By Jay Fingers / Be Cool Books, 218 pp.,

$24.95 (cloth), $14.95 (paper)

The history and culture of Orange Mound is both fascinating and unfortunate. The first community to be built and sustained by African Americans in Memphis, it has diminished over the decades as a result of high crime rates and teen pregnancy. The novel Orange Mound by Jay Fingers, a native Memphian now living in Brooklyn, captures the hardships experienced by a cast of Orange Mound characters and how those hardships can be both inspirational and detrimental.

The novel revolves around Ant, a young, humble drug dealer with aspirations of going legit. After a routine transaction turns into a life-changing situation, Ant trades his illicit activities for his dreams of becoming a chef and owning his own soul food restaurant. In the midst of his career change, Ant meets Tuffy, a gorgeous hair stylist who’s pulled the plug on a demeaning relationship and is secretly a drug courier. The two develop a friendship that quickly evolves into a passionate love affair. But their separate dealings with the Memphis City Syndicate, a drug-trafficking ring, come back to haunt them.

The novel also highlights how Ant’s best friend, Cornelius, a local drug peddler, isn’t too thrilled about Ant’s decision to leave the drug game. Cornelius’ determination to become a prominent figure in the Syndicate — along with his links to Gigi Garcia, a beautiful woman with an appetite for murder — guarantees disaster for anyone in his way. Ant is no exception, and after he becomes aware of Cornelius’ deceptive, greed-driven ways, Ant’s life, along with Tuffy’s, is placed in jeopardy.

Orange Mound is filled with humor and romance but also drama and suspense. Relatively explicit, it’s not appropriate for all ages, but it’s a thrilling read for any fan of urban fiction. — Louis Goggans

Cornbread Nation 7: The Best of Southern Food Writing

Edited by Francis Lam

The University of Georgia Press, 273 pp., $24.95 (paper)

My sister hasn’t lived in the South for two decades, but the region looms large in her imagination. She has these huge and romantic truths she shares with her L.A.-raised husband — truths that paint the South with a broad and humid to the point of steamy brush. It’s a place where women, no matter what, dress in their finest and in full makeup to go to the grocery store.

Notions of the South are just that, notions, and apply to any place. (Who’s to say the ladies in Seattle don’t put on their finery for the store?) It’s this dilemma that New Jersey native Francis Lam, editor of the seventh edition of the Southern Foodways Alliance’s Cornbread Nation series, addresses in a sharp and knowing fashion. You see it in the very first sentence of the introduction. Lam writes, “In my younger, more offensive years, I used to say that Michigan was the South’s northernmost state, on account of the popularity of pickup trucks and country music.”

The collection of Southern food writing that Lam has gathered spans decades and is smart and oftentimes flat-out funny. As to the latter, it’s seen in Bill Heavey’s amazing “Grabbing Dinner” about frog hunting in Louisiana and Dan Baum’s often hilarious “Hogzilla” about wild-pig hunting in Texas.

The real prizes of Cornbread Nation 7, though, are the eye-opening essays that address “otherness” in the South. Eddie Huang’s “God Has Assholes for Children” is a sweet ode to his mother, who backed him no matter what. “Mississippi Chinese Lady Goes Home to Korea,” by Ann Taylor Pittman, details how the author was inspired by a child’s comment (“Hey, Chinese lady!’) to explore her Korean roots. Other fine essays include Julia Reed’s “The Great Leveler” and Lolis Eric Elie’s “Willie Mae Seaton Takes New York.” — Susan Ellis

River of Hope: Black Politics and the Memphis Freedom Movement, 1865-1954

By Elizabeth Gritter

University Press of Kentucky, 356 pp., $40

Elizabeth Gritter is the latest of an increasing number of gifted historians aspiring to document the struggle for civil rights and political self-sufficiency for blacks in Memphis prior to the epochal Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954. What she chronicles in River of Hope becomes a stream of useful information about brave and resourceful African-American pioneers — progressing from post-emancipation hopes to early 20th-century avatars like Robert Church Jr. and J.B. Martin, entrepreneurs who did their best to develop black pride and capability in an age dominated by the de facto dictatorship of Boss Ed Crump.

This was an age of paternalism in which blacks had some patronage benefits and could vote as directed and one in which a prominent local laundry could advertise its services with pictures of servile black workers washing dirty white underpants.

Church and Martin, who attempted to channel opposition to Crump into black Republican organizations, were both forced into exile and succeeded locally by such enduring leaders as Lieutenant George Washington Robert Lee, a World War I veteran whose scaled-down activities via a Republican “Old Guard” in black communities were better tolerated because they were considered less threatening.

Spurred on by the statewide election successes in 1948 of white anti-Crump Democrats like Estes Kefauver of Chattanooga and Gordon Browning of Huntington, a new crop of African-American politicians — some Republicans, others Democrats in alliance with the new anti-Crump white leaders — came to the fore. The author then segues her story into plotlines with characters whose names are more familiar to our own time, men like Benjamin Hooks and Russell Sugarmon, who between them marked the transition from Republican to Democratic loyalties among Memphis blacks.

River of Hope is an eminently readable, almost novelistic account of how several generations of reformers finally fused into a movement destined, at least in certain basic ways, to overcome. — Jackson Baker

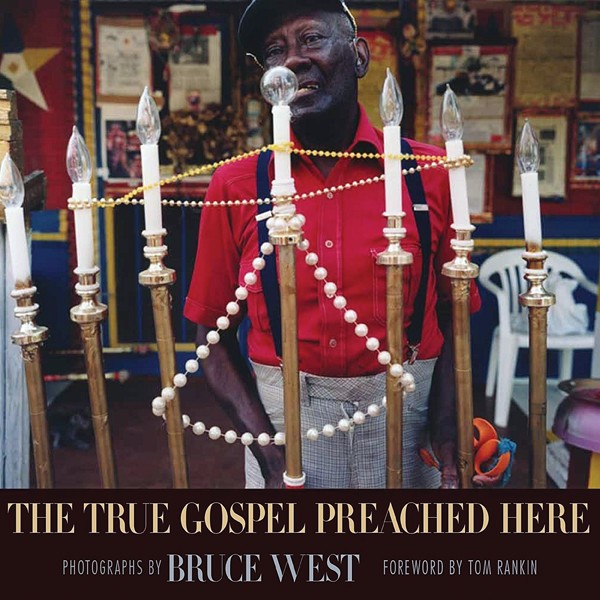

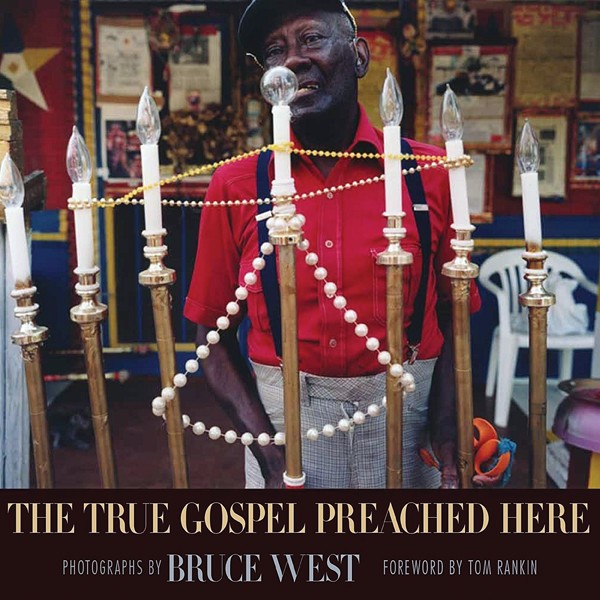

The True Gospel Preached Here

By Bruce West

University Press of Mississippi, 65 pp., $35

I’m not religious, but I probably could have found Jesus at Margaret’s Grocery in Vicksburg. Or at least I would have enjoyed listening to the far-out gospel according to the Reverend H.D. Dennis and his wife, Margaret.

The elderly couple ran a roadside grocery store/nondenominational church/living folk-art gallery in their Mississippi home for years before the reverend’s and Margaret’s deaths in 2012 and 2009, respectively. The garish abode was decorated with hand-painted signs proclaiming God’s love for all and instructing passersby to read their Bibles. All manner of bits and baubles — empty egg cartons, hair ties, stuffed animals, plastic flowers, and enough Mardi Gras beads to supply all the topless women in the world — were glued to every square inch of the inside and outside of the grocery store and school bus, which acted as the church sanctuary.

Bruce West, professor of art at Missouri State University, discovered Margaret’s Grocery on Highway 61, and he couldn’t resist stopping in to photograph the couple’s roadside attraction. But before he could snap a photo, Reverend Dennis invited West into his school-bus church, its front windows covered with a faded print of the Last Supper, for a bit of evangelizing. Naturally, the photographer was intrigued by Reverend Dennis’ approach to worship, and before long, an intimate bond was formed. West visited the couple time and again over the course of 20 years, documenting the ever-evolving art of the church. Surfaces were continually being painted over, and in the couple’s later years, Margaret added her own touches of pink and yellow to the reverend’s red-and-white color scheme.

Eventually, the African-American couple began referring to West as their “white child,” and the reverend even asked West if he’d take over the church as his health began to fail. West politely declined, but he continued to document the couple and their art until their passing. His gorgeous full-color photographs in The True Gospel Preached Here stand as a lovely tribute to a couple whose love for God was their art. — Bianca Phillips

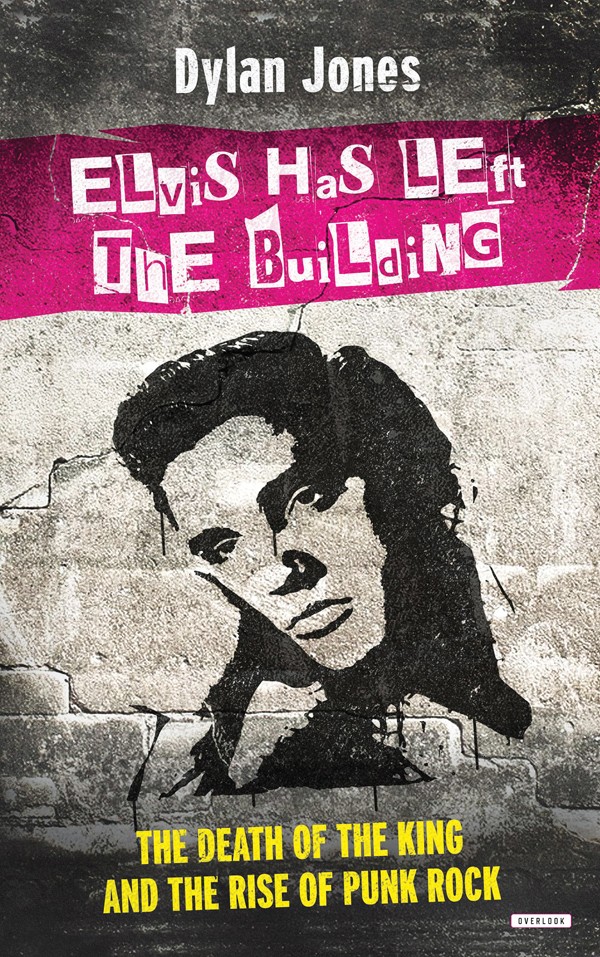

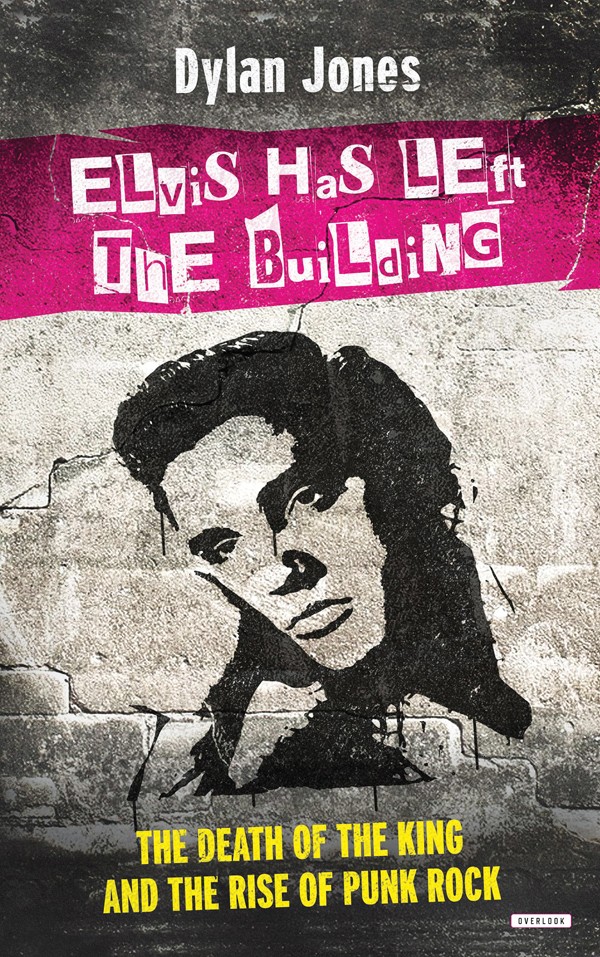

Elvis Has Left the Building: The Death of the King and the Rise of Punk Rock

By Dylan Jones

The Overlook Press, 295 pp., $27.95

Dylan Jones is a fashion writer. Let’s get that out in the open before we slog through his book about the cultural revolution that passed a torch from Elvis Presley to John Lydon. Jones’ book Elvis Has Left the Building (official publication date August 16th) is in some ways about Elvis, but it’s primarily about 1977, the most overanalyzed year in music criticism.

Jones has a point to make: Rock (Elvis) got fat and some folks from New York and London traded the gilded Cadillacs and gaudy mansions for music that was whittled down to an angry minimum. Jones’ strength as a writer lies in his ability to tie the Lancaster and Tudor schools of rock into the personal histories of people whose very identities were derived from the King or Johnny Rotten.

I’m not sure the world needs another discourse on how the Clash appropriated Elvis’ hair and album art. And while any further writing on the Ramones and Iggy Pop is perhaps interesting to someone out there, it’s not to me. The problem with analyzing punk is that it intentionally stripped away all pretenses. So the application of intellectual rigor not only misses the point, it makes the reader want the writer to die on the john. And about that john …

Jones is the editor of British GQ and winner of the British Society of Magazine Editors’ Editor of the Year Award. Anyone who has read Evelyn Waugh or most of what many Brits write can’t have much hope for decorum and manners. So if you’re looking for a detailed description of Elvis’ corpse being crammed into its coffin or of the panic his attendants endured upon his demise, this is your volume of history. Others may decide there are more important things to read. — Joe Boone

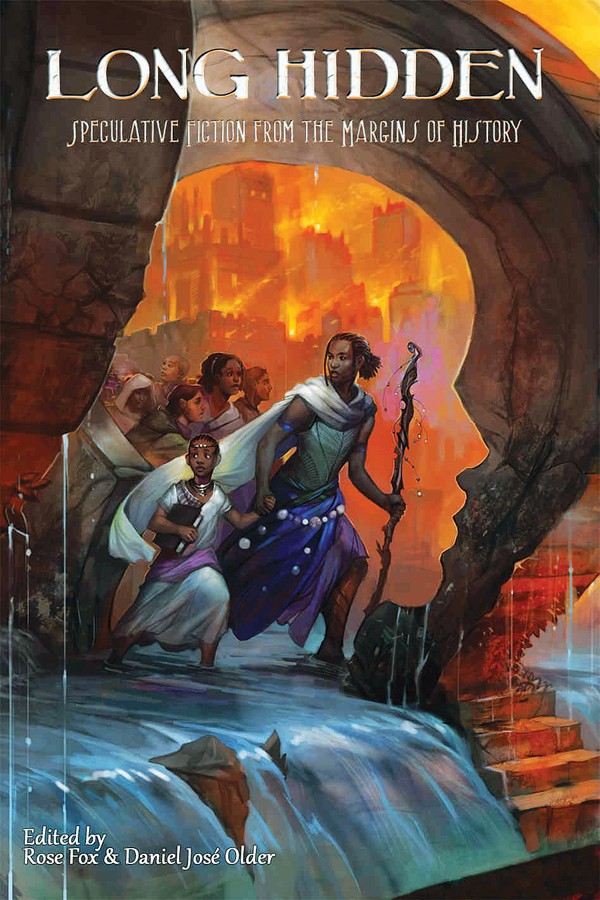

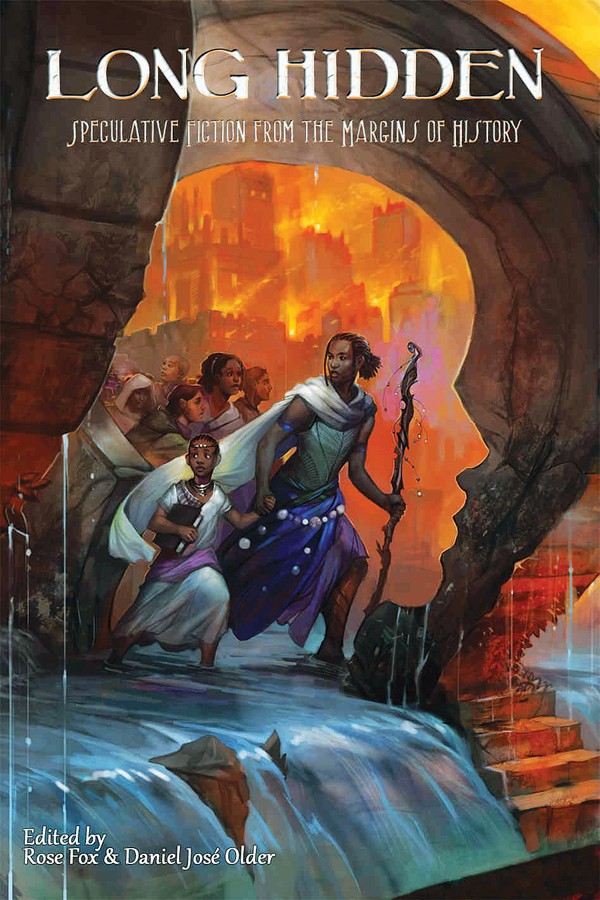

Long Hidden: Speculative Fiction from the Margins of History

Edited by Rose Fox and Daniel Jose Older

Crossed Genres Publications, 370 pp., $19.95 (paper)

When you think about it, perhaps the most unbelievable thing about most Western tales within the supernatural, sci-fi, fantasy, horror, and other speculative fiction subgenres is the fact that the heroes are all white dudes.

That’s in part because so many of the writers have been white dudes, though there are plenty of exceptions, including Octavia E. Butler, Walter Mosley, Samuel R. Delany, Sherman Alexie, Gabriel García Márquez, Pauline Hopkins, David Anthony Durham, N.K. Jemisin, and even W.E.B. Du Bois.

The editors of a new anthology, Long Hidden, take it a step further. And like the anthology series Dark Matter, it’s a step in the right direction. The introduction to the collection frames Long Hidden as “representations of African diasporic voices in historical speculative fiction, and the ways that history ‘written by the victors’ demonized and erases already marginalized stories” — the stories about the “victors” commonly promising “to take us to places where anything was possible, but the spaceship captains and valiant questers were always white, always straight, always cisgender, and almost always men.”

Not so in Long Hidden. And of note: Two of the stories are by Memphians: Jamey Hatley and Troy L. Wiggins.

Hatley has written for Oxford American and has won the William Faulkner-William Wisdom Award for a Novel-in-Progress. Her story here, “Collected Likenesses,” takes place in Harlem in 1913. It’s a slow-boil about freed slaves, the lingering “wounds of bondage,” and patient revenge, and it has a nice twist ending.

Wiggins’ “A Score of Roses” is set in Memphis in the 1870s, not long after the city’s race riots (that part of the narrative is not speculative). Sunshine, a passionate woman, meets Baby, an earthy, old soul. The two hit it off, maybe because there’s something special about each of them.

“A Score of Roses” is more folk-fantasy, about fire and persistence and hereditary memory, while “Collected Likenesses” is more domestic horror. But both stories show the breadth of what’s possible in speculative fiction and what’s possible when new voices join the conversation. — Greg Akers

Second Editions 2.0: You Are There

The good folks at Second Editions at the Central Library (3030 Poplar) have an announcement to make: In addition to the fine-quality used books, music, and DVDs for sale, the store has expanded its selection of children’s books, young-adult titles, and paperback adult fiction. It is also offering signed books on a permanent basis, with new titles introduced every couple of weeks. You can now find paperback advanced readers’ copies of brand-new books too. They’ll be available 90 days after the publication date of the hardback edition, all advance copies priced at $2 each.

And that’s not all. The store has introduced vintage paperbacks from well-known writers such as William Faulkner, Erskine Caldwell, Lawrence Durrell, Damon Runyon, and C.S. Lewis, as well as books by mystery and western writers. All are priced to sell, according Herman Markell of the Friends of the Library, which operates Second Editions — meaning, you won’t find prices this low, even on the internet.

It’s also important to note that all money generated by Second Editions sales — together with the library’s community-donated material sold on Amazon and the library’s semiannual, citywide book sale — go 100 percent to the Memphis Public Library system. That’s an annual $400,000 going back into the library’s operating budget, a point that’s important for Memphians to remember.

The expanded Second Editions has been operating for only two weeks now, so it’s perhaps too early to judge customer response, according to Second Editions Manager Antonio Quinn, who worked with others at the library (“co-conspirators,” he called them) on the idea of expanding the store’s offerings and categories. On the topic of future expansion, Quinn is, however, taking a cautious approach.

“It depends not only on the demand but the space,” he said. “It’s pretty packed now, and the only direction we can go is up, so we’d have to get more shelving. We’re at a point now where if we put anymore out, we’re going to look like a rummage sale. We’re trying to avoid that look.”

“Entering our 12th year, Second Editions is thrilled to now speak of our ‘new and improved store’ — improving on what is arguably the best and least expensive used book store in the Mid-South,” Markell added in an email. “More and more people are enjoying our amazing selections. And best of all, every penny of profit goes back to support our entire Memphis Library system. See for yourself, in the lobby of Central Library. Turn right after entering, and you’re there.” — Leonard Gill