Anima/Animus,” Kurt Meer’s current exhibition at L Ross, references Carl Jung’s designation for the feminine/masculine qualities that exist in us all. A thoroughbred horse — a creature that is both graceful and strong, majestic and grounded — stands at the center of Still. Ears pricked, alert and calm, the thoroughbred gazes out over the landscape. The wide range of siennas and umbers that color the animal’s coat look as fertile as the freshly plowed earth on which this mare (or stallion) stands. The moist soil and silken fur reflect the lavender sky. Though no searing suns, no billowing clouds roil our point of view across the surface of his paintings, Meer’s skies feel all-encompassing and alive. Soft blue seamlessly gradates into silver into lavender into the radiant pink that borders the white-gold mist near the center of Clouds I. Peering into this painting — so accurately observed that every particle of moisture seems to vibrate with light — it feels certain the sun will soon break through.

Opening reception May 6th, through May 28th

In Memphis College of Art’s group show “The Greece & Crete Studio Elective Workshop,” architect and environmentalist Clark Buchner explores the fragile boundaries between line and form and illusion. The thick eroded walls and ramparts in the digital image Tree in Courtyard, Palace of Knossos, Crete, Greece suggest that some important monument or religious edifice lies just beyond our point of view.

Buchner, however, isn’t drawn to the grand or merely picturesque but to scenes that etch more indelibly into memory. He shoots low to the ground, accentuating the rubble in the courtyard and the decay at the base of the walls. The shadow beneath the trunk of a tree feels as tangible as the object that cast it. By placing the tree in the foreground of the image, Buchner suggests this leafless sentinel is as important as the ruined walls it guards.

Through May 9th

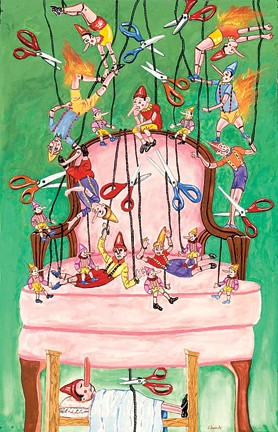

Larry Edwards, Pinocchio’s Dream 2, at the Dixon Gallery and Gardens

For decades, accomplished colorist, social satirist, and hell-and-brimstone preacher Larry Edwards has explored “the three F’s — the foolishness, foibles, and frailties of human behavior.” The Dixon Gallery and Gardens’ current exhibition, “3 Themes,” contains some of Edwards’ most unnerving artworks yet. In his saturate/surreal gouache, pastel, and watercolor painting Pinocchio’s Dream (2), multiple Pinocchios tumble and fall as scissors cut through their strings. Unseen forces set other Pinocchios on fire. Far right, a pair of scissors are about to cut the legs of yet another Pinocchio.

In another chapter of Edwards’ retelling of the children’s classic, Armored Noses Admiring Pinocchio, a blood-and-flesh Pinocchio — now a real boy — balances on three disembodied and helmeted heads stacked on one another. Pinocchio sports a nose that looks phallic. Noses and/or tongues (another body part adept at bearing false witness) protrude from the helmets.

In Pinocchio Falls into the Inferno, Edwards has his subject paying for his transgressions. But in The Phoenix, it’s another story, one which the artist describes as “a happy ending … the mythical bird and Pinocchio rise, reborn from the flames.” In Edwards’ oeuvre, however, entries into heaven and exits from hell are never easy rides. With a smile that looks more maniacal than transcendent and a nose that is, alas, as long as ever, Pinocchio is spewed into a pitch-black world where clouds are dense and brown.

Manipulated by unseen forces, easy prey to flattery, driven by desire, and possessing multiple personas, how can Pinocchio, or any of us, speak to truth? One thing, however, feels certain: Edwards — a tireless painter and retired professor emeritus now in his 80s — is edgier and more ironic than ever.

Opening reception May 19th, through July 24th

In Harrington Brown’s current exhibition, “Two Rivers,” the swatches of color on the surfaces of David Hinske’s paintings look as shot through with light as the Taos home in which he works. The rhythms of Hinske’s brushstrokes — by turns staccato and fluid, impastoed and full-throated — mirror improvisations of the jazz music playing in the background.

In works like In the Kitchen, Digging in the Pantry, and Basil (In a Can by the Window), what looks abstract is most real for this painter/chef/musician who multi-tasks. Hands on the meal prep as well as on his brushes — slathering oils onto canvases as high-key as the notes of a sax, pulling sprigs of fresh herbs from orange-lipped canisters, and peeling/slicing/dicing tomatoes and yellow peppers for the soup simmering in a kitchen that also serves as one of Hinske’s studio spaces: Everything is in motion.

Opening reception May 6th, through May 31st