Near the corner of Vance Avenue and Danny Thomas Boulevard, you can’t miss the faded blue sign that extends toward the sky. Among the vacant lots and graffitied abandoned buildings on the block, that sign, in its art deco style, is one of the few surviving hints at what once was a vibrant neighborhood and community. Its letters don’t light up in neon anymore, but it once read Griggs Business College.

Griggs Business and Practical Arts College, to be precise, would be the white Italianate building behind that sign at 492 Vance. Chartered in 1944 by Emma Griggs, the college was initially one of three Black colleges in Memphis, the others being the now-demolished Henderson Business College and LeMoyne College, which later merged with what would become Owen College. More than 1,000 Black men and women received their education at Griggs. In 1971, though, with declining enrollment numbers and under financial hardship, the college closed its doors. In 1974, the 492 Vance property was sold to the Bluff City Elks Lodge, who remained there for close to 10 years, but it’s changed hands multiple times since then, remaining empty since the late 1980s.

And yet, even as the building itself has become a shell of its old grandeur, its front steps cracking, tree rot taking over the grounds, the inside losing semblance of a once livable space, the college and its legacy hasn’t been forgotten. Over the years, Carrie Tippett-Herron, who graduated from Griggs in 1967, sometimes would drive by the school, curious to see if anything had happened to her old stomping grounds. “Not only me, but a lot of other [alumni] would come down, drive down through here sometimes,” she says.

But alumni weren’t the only ones paying attention to the property. In 2016, Stephanie Wade, a native of Memphis, discovered Griggs, not knowing anything about its history. “I think a lot of people have seen it but don’t know anything about it,” she says. “It’s hard to miss because it’s on a hill. It has a presence. And that’s what happened to me. I was living Downtown and I wanted to get into real estate. And I began paying more attention to the community and the buildings and such. And this one just always stood out to me. It just called to me. It felt like it refused to be forgotten.”

By 2020, Wade found out the property was set for demolition to make way for a gas station. “I’m not the kind of person that’s like, someone should do something,” she says. “I’m always like, if I feel something should be done, then what am I doing about it? So from there, it just kind of snowballed. … At that point, my heart was in it, and, no matter if it made sense or not, something had to be done.”

So Wade bought 492 Vance as her first development project, with plans to turn the building into one that is multi-use and that can serve the community as it stands today. For this, the Griggs Legacy Project, she’s engaged the help of alumna Tippet-Herron; Sheryl Wallace, president of the relatively new Property, Power, and Preservation (P3); and others. It’s a community effort, she recognizes.

“I feel like we, as the Black and Brown community, need more representation in the built environment,” she says, “to be able to see different places that we were a part of, that are a part of our communities. And when you see something like this, you begin to think, ‘What is that? What happened?’ And it’s just by happenstance. You didn’t go to a museum or you didn’t go to some place to learn more about your own culture. You were just walking up the street, going down the street, and realized or saw something that piqued your curiosity. And so I feel like that’s where I want to make a difference. This is one of the ways to do it.”

A Brief History

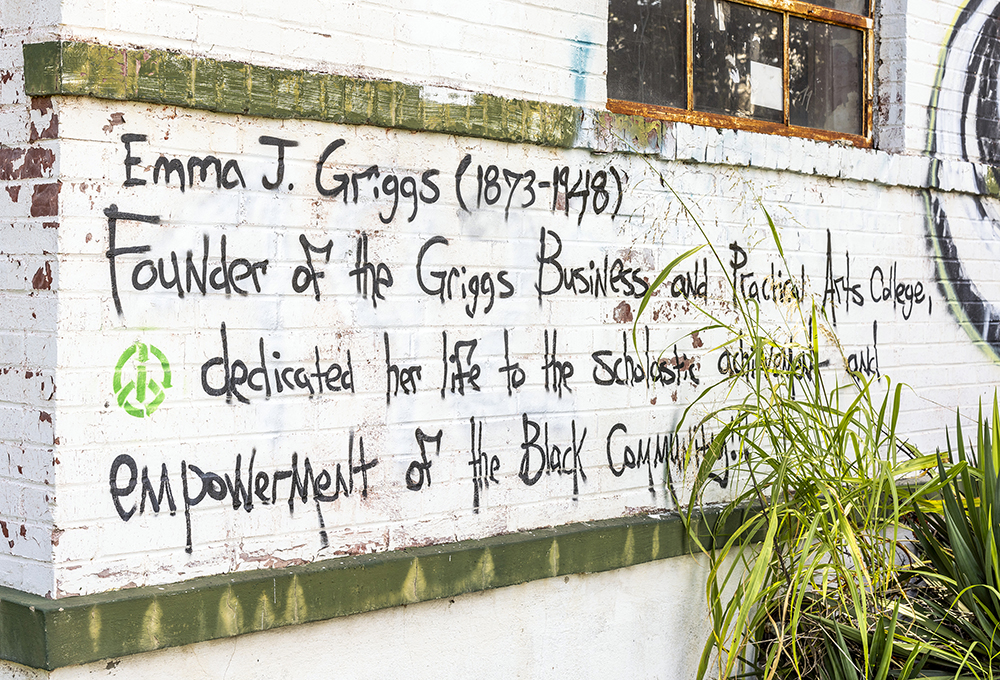

It’s fitting that the Griggs Legacy Project, which is spearheaded by women, finds its origins in the little-known history of Emma J. Griggs (1873-1948). “Emma is a figure in her own right,” Wallace says. “And that’s something to say for a woman in that time.”

A lifelong student and educator, Emma grew up in Virginia and, writes Antoinette G. van Zelm in Emma J. Griggs: A Lifelong Commitment to African American Education in Nashville and Memphis, “it is likely that her parents [who were probably born into slavery] instilled in her a deep love of education, no doubt sharing the reverence for learning that has been documented among Civil War-era African Americans, especially those formerly enslaved, in the South.”

Emma would go on to marry Sutton E. Griggs, a well-known Baptist minister, writer, orator, and civil rights leader, in 1897. In 1889, the couple relocated from Emma’s Virginian hometown to Nashville, Tennessee, where Sutton served as pastor of the First Baptist Church and Emma founded a small school.

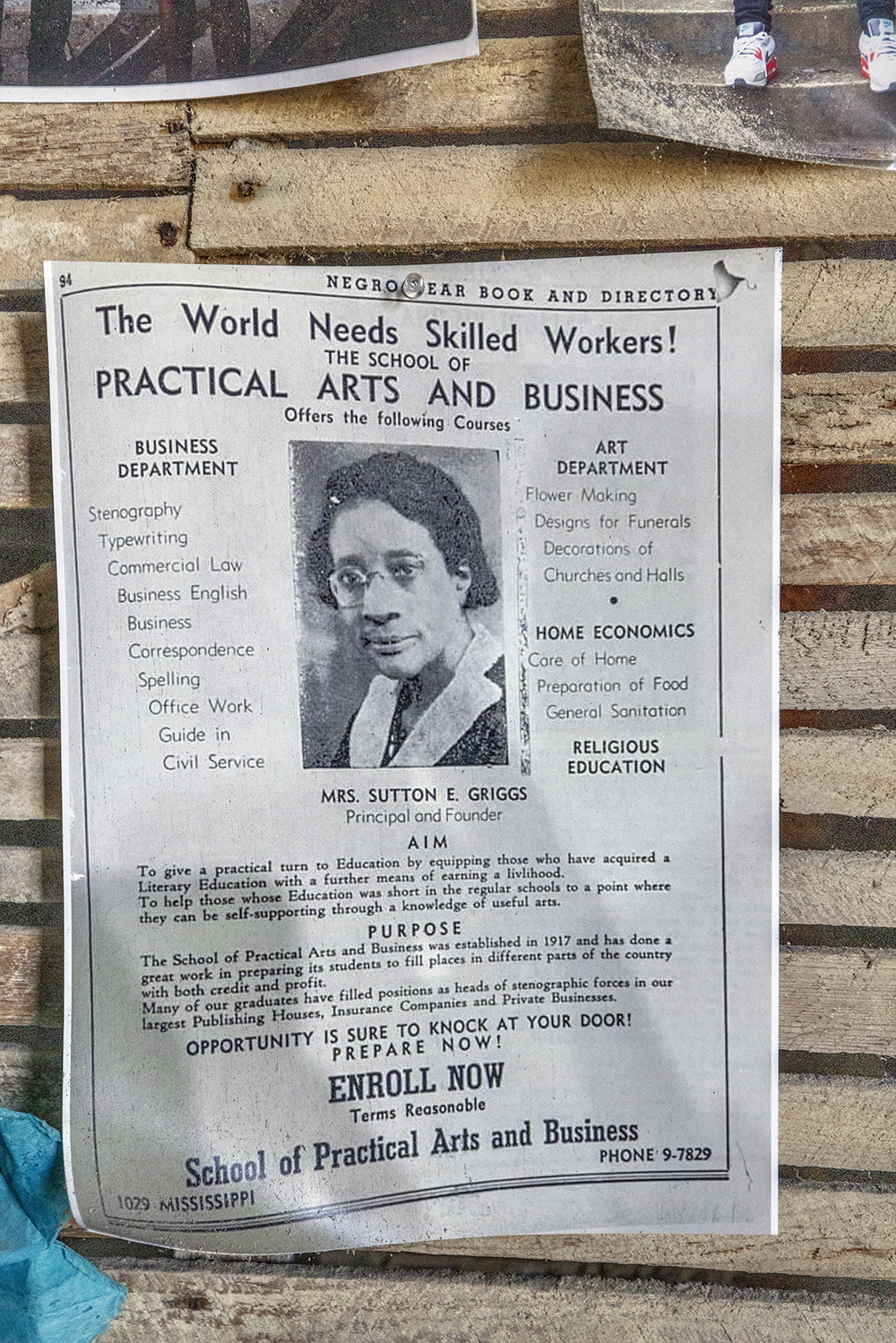

In 1913, they moved to Memphis for Sutton to take over leadership of the Tabernacle Baptist Church. Emma, for her part, ran a “practical arts school” out of their home and later out of the church, teaching cooking, stenography, personal services, and performance arts to classes of women. Its first commencement ceremony was held in May of 1916; this would be the beginning of what would become Griggs Business and Practical Arts College.

At the onset of the Great Depression, the couple moved to Texas, and just three years later, in 1933, Sutton died at the age of 61. Emma returned to Memphis, and she came with a goal: to establish a school in his honor.

Soon after, she opened a small school at 741 Walker, later moving the facility to a few other addresses. She added business classes and launched a funding campaign, and by 1944 she’d chartered the school as the Griggs Business and Practical Arts College. The following year, Griggs established its campus at 303 South Lauderdale, where it would be until Emma’s death in 1948.

Notably, Emma did all this while living within a segregated city systematically set against her. Jim Crow reigned, and the threat of racial violence cast a shadow over Black people’s livelihoods. Just one year after seeing the first class graduate from her practical arts school in 1916, Memphis succumbed to extreme violence in the lynching of Ell Persons, one of the most vicious lynchings in history, which led to the creation of the Memphis chapter of the NAACP. The site of the lynching would be approved for the National Register of Historic Places the same day as Griggs in 2023.

“I must say it hit me hard during the national register process to get it listed [as a historic site],” Wade says. “We went to Nashville when the state approved it [last spring], and it hit me hard to hear them talk about Emma because I believe during her time she didn’t get the credit she deserved. So to finally hear someone else say her name out loud for her contributions — and not Mrs. Sutton Griggs or Mrs. Griggs, kind of always behind his shadow — she was getting recognition on her own of what she was able to achieve. To hear them say that, I almost came to tears.”

Today, a portrait of Emma by David Yancy III is spray-painted across the front door, a reminder to all who cross the threshold of the woman who started it all.

The School

Tippet-Herron, who once walked those halls as a student when the building was in its full glory, says she learned about Emma and Sutton Griggs through word of mouth from her teachers. “I never got any books until [Wade and Wallace] came here to teach us. See how it works? Things are beginning to come full circle now, with what [the Griggs Legacy Project is] doing.”

Each morning before classes at Griggs, Tippet-Herron’s father and sons would help her up the steps before they went off to their construction job and she went off to learn; her stepmother would make all of their lunches. “When we got out of school, [my father] would be right down at the steps, him and the boys waiting on me to come out, his station wagon full of paint cans,” she says.

Tippet-Herron had enrolled in the college after earning a scholarship through the Urban League and her church. Among her classes were English, business law, accounting, mimeograph, and personality. “The worst thing I did was the shorthand. I could write it out, but I couldn’t read it,” she says. “They laughed at me.”

There was also that one accounting problem. “I worked and worked and worked and every time I came out a penny short. And one day Reverend Gaston [director of the school] got up and told me at church, ‘Miss Carrie,’ he said. ‘Come here. Come to the office, and we’re going to pray for you.’ He said, ‘Why are you always crying?’ He said, ‘Nobody that I have ever known has ever solved [that professor’s] problems.’ He said, ‘You stop that crying.’”

Even with that one problem and shorthand, Tippet-Herron describes her experience at Griggs as “great.” “It was a blessing,” she says. “Because the math, the law part, and everything helped me deal with the job that I had at Levi Strauss. … My business law professors would say, ‘You gotta really know what you’re doing. You gotta understand the things that come before you. You gotta know what to do, how to handle it.’ … So Griggs helped me; Griggs helped me to set my life on a wonderful path.”

Hundreds of alumni, a number of them veterans, can surely say the same. A few notable graduates include Kathryn Bowers, who served as a Tennessee state representative from 1994 to 2006; MaryAnn Johnson, the first Black woman to head the music administration department at Twentieth Century Fox; J.P. Murrell, a local music promoter, co-owner of the Harlem House restaurant chain, and 1975 Urban League “Man of the Year”; Rev. Lee Rogers Pruitt, for 40 years the pastor of Tabernacle Missionary Baptist Church (the same congregation that Sutton Griggs had served decades earlier); and Julian C. Benson, who was appointed assistant Shelby County jury commissioner in 1973 and in 1980 became the commission’s first African-American chairman.

When the school closed, Tippet-Herron says, “We were all sad. The whole church was sad.”

492 Vance

Emma Griggs never saw Griggs College at 492 Vance, where Tippet-Herron attended school. Emma’s successors purchased the property in 1949, a year after her death. The building was originally built in 1858 as a private residence for attorney Joseph Gregory, whose family lived there for some 50 years in what was the mostly white and affluent neighborhood of Vance-Pontotoc at the time. By the 20th century when Griggs College moved in, the neighborhood had become a hub for African Americans after most of its white residents moved eastward as the city grew.

According to Tippet-Herron, who grew up in the area, it was a thriving community, full of residential businesses like Bodden & Company School of Tailoring, Little John’s Cabs, and Leon’s Supermarket. “There was a florist, too,” she says. “She taught floral arranging. She didn’t have a school, but she had a flower shop and taught the young girls how to do flowers.

“There’s a lot of history here,” she says. “This man would go through the neighborhood and pick up old shoes that were thrown away — the brown-and-white, black-and-white saddle oxfords. He would fix them up, cut the soles, and give them away to children. He was so talented. That’s the kind of history that people don’t know about. And it was in this area around here.”

As the years went on, and as white flight led to the deconcentration of wealth within historic African American communities and urban renewal displaced middle-class African-American neighborhoods, the neighborhood lost its vibrancy. Indeed, the Vance-Pontotoc Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 for the architectural significance of buildings like 492 Vance, but was delisted in 1987 as fires and demolition scourged the area.

Be it fate or happenstance, the Griggs College building remained through it all, and now thanks to the work of the Griggs Legacy Project, it will remain for years to come. “There’s a need not to let our legacies go,” says Wallace. “We need to hold on to our history as much as possible. Henderson no longer stands.”

Henderson, one of the two other Black colleges at the time, faced many of the same struggles as Griggs and was demolished after its closure in 1971. LeMoyne-Owen College is the only historically black college and university (HBCU) remaining in the city.

“But we lucked out with Griggs because the building is here [even though the college is not],” Wallace says. “It’s like, whoa, this is a hidden treasure that we need to let the people know about again. Let’s get excited about it again. Memphis has grown so much. This area has grown as well, so we feel like this is a perfect place to start again.”

Wallace, for her part, has always been interested in history, but, like Wade, did not know much about the school prior to working on this project, despite being a lifelong Memphian. She’s now the president of Property, Power, and Preservation (P3), a nonprofit founded last year with a focus on historical preservation. Working on the Griggs Legacy Project has been their first endeavor.

“One of the challenges that we face is collecting the history,” Wallace says, pointing out that a lot of what they do know about Griggs has been piecemealed together through archival research. “There’s not that much documentation that you can really find. It would be great if we could get more dialogue about it.”

Wallace hopes more alumni like Tippet-Herron and their families will reach out with stories; she dreams of getting her hands on a yearbook, a diploma, or a graduation gown. “You never know what you’ll find when you start going through attics,” she says.

“And a lot of its history is passing,” Wade adds. “It’s a sign of the aging population. Capturing as much as we can before it’s all gone would be great.”

Keeping a Purpose

While much of historical preservation is about the past, it’s also geared toward the present and the future. The women behind the Griggs Legacy Project see its history not as stagnant but as a sustaining, life-giving foundation for them to build upon.

“My hope for the project is that it’s not just a building, but it serves the community,” Wallace says. “It’s something that’s needed.”

They plan to preserve the historical integrity of the 4,200-square-foot building, keeping as many of its Italianate features as they can, but also reimagining its purpose. It’ll be a multi-use building of some kind, though what exactly is unknown. It could see some apartments on the second floor; it could house a technology incubator. “I would like to see maybe a store with a focus on health,” Wallace says. “Being that we are in this particular neighborhood, you have to think about all the issues faced with not being able to have healthy foods [readily accessible].”

Whatever form the building will take, Wallace and Wade know the space will be for the community. “It’s always been a community effort,” Wade says. “The community has always been a part of it, every step, every piece, and that’s why we have this partnership. When Sheryl [Wallace] and I talk, it’s always, ‘How can we do this collectively?’ There are so many different organizations doing things in the neighborhood. There’s Steve Nash at Advance Memphis. There’s MIFA a couple of blocks east. There’s Streets Ministries a couple of blocks west. There’s the [Historic] Clayborn Temple.

“I think there’s such a negative connotation around the word ‘developers,’” Wade adds. “I understand why, and I’m just trying to paint a different narrative because it doesn’t always have to be that way. I think development can be great.”

For Wade, whose background is in urban planning and community programming, this is her first development project; it’s her baby. (As Tippet-Herron jokes in good nature, it’s in the crawling stages right now, set to start construction possibly next year.) But Wade wants to do it right. That means making sure the project is, yes, community-driven, but also environmentally sustainable. “This project is definitely not your regular real estate development,” Wade says. “It’s so much more meaningful and purposeful in every aspect of it, in the use of what’s going to be here, in the construction, how we make sure we’re paying attention to the history of it, but then also making it sustainable, environmentally-friendly, both the in construction materials and in the process.”

Needless to say, an initiative of this caliber will cost a lot. So far, the Griggs project has secured $750,000 in funding from the African American Civil Rights grant program through the Historic Preservation Fund, administered by the Department of Interior’s National Park Service, as well as a $300,000 Tennessee Historic Development Grant from the Tennessee Department of Economic and Community Development.

These grants have made a huge difference when it comes to financing the Griggs project, Wade says. “You don’t have to cut costs. You could just go the cheapest route, but, no, we were able to get a grant for this, so we can really be intentional about how we do this. When you take on debt where you’re like, ‘We’ve only have so much money, and we need to get this thing going,’ you start cutting corners because you’ve have to start paying back the debt.

“This work is not easy,” she adds, “and for me, if I’m putting that much time and energy into something, it has to be purposeful. And, of course, I don’t want to go into debt with any of it, but I mean, there’s a way, right?”

Wallace and Wade hope to secure more funding and they hope the community shows up, too. “We may need pro bono services at first, until we can get up on our feet and get additional funds and then start paying out,” Wallace says. That may look like someone providing lawn-care or helping with the documentary they plan to make.

“I would love to get back to what it was as we were hearing from Ms. Carrie [Tippet-Herron],” Wade adds. “It was really a community. You had neighbors and businesses and churches working together, supporting each other.”

When asked about her hopes for the project, Tippet-Herron beams. “I’ll tell you my beliefs. I believe it’s going to be successful and it’s gonna help revitalize not just this little area but the whole area of this section of the city of Memphis,” she says. “When I feel like it, I’m gonna call my buddies, my prayer warriors. It’s gonna come to fruition.”

For more information on the Griggs Legacy Project or to find out how you can help, email griggslegacyproject@gmail.com.