Jamila Wignot was nervous. It was Friday night, May 17, 2024, at Crosstown Theater in Midtown Memphis, and she was about to premiere the first episode of her latest HBO documentary series Stax: Soulsville U.S.A. to a hometown crowd. The sold-out house was full of Memphis music royalty: David Porter, Al Bell, Deanie Parker, Eddie Floyd, the list goes on.

“It’s like somebody was just saying to me, ‘Didn’t Janis Joplin get booed in Memphis?’ And I was like, ‘Exactly!’ That’s why I was nervous,” Wignot says on a Zoom interview a few days later.

Turns out, she needn’t have worried. The crowd responded to “Chapter One: ’Cause I Love You” with a Cannes-level standing ovation. During the Q&A after the screening, Deanie Parker, the Stax Museum of American Soul Music’s first CEO, seemed taken aback. “This really has been an emotional experience for me,” she says. “I think it’s because, while we achieved a lot, we did it in about a decade — which is astounding! We made a mark globally.”

Collection/OKPOP)

Wignot says her involvement with the Stax story started as she was finishing up her last documentary, a portrait of modern dance pioneer Alvin Ailey. “I’ve been working in documentary filmmaking, particularly historical documentary filmmaking, for a long time. But I came out of a kind of PBS model of documentaries that were narrated by a kind of ‘Voice of God’ narrator. They used archival [film and stills], but there were very specific ways that you had to use it at that time. With Ailey, I finally got to do the kind of documentary filmmaking that I like to do, which is first-person, kind of witness-driven documentary filmmaking. As a kid, I saw Eyes on the Prize and thought, ‘Wow, this is amazing!’ When you are hearing from somebody who was there on the front lines, and then you’re seeing them in the archival footage, it all just feels very immersive and alive and urgent.

“On the heels of that, I was then approached first by Ezra Edelman and Caroline Waterlow who made O.J.: Made in America. We’d all been friends for a very long time. Ezra said, ‘I’m working with this company, White Horse Pictures, and we’re looking for somebody who wants to direct a series on Stax Records, and do you think you’d be into it?’ And I was just immediately like, ‘Yes, yes, yes!’”

Stax: Soulsville U.S.A. skillfully blends interviews with the surviving players and extensively researched archival footage from the label’s heyday. “I don’t bother to interview RZA, who’s a diehard fan of the label. There’s no Justin Timberlake, there’s no Elton John, there’s no Paul McCartney. I was not interested in having the kind of secondary fan in there, just appreciating it. I wanted to understand how the label came together, the experiences of the people on the ground, and then let the music do the work of generating enthusiasm.”

The story is one of triumphant highs, stunning reversals of fortune, and missed opportunities, such as the time The Beatles tried and failed to schedule a recording session at the Stax studio on McLemore Avenue. (“Had that happened, for sure Ringo and Paul would’ve been up in this documentary!” says Wignot.)

Wignot’s approach is immediate and visceral. In one priceless take, shot in Booker T. Jones’ Nevada home, the Stax organist and arranger walks us through the creation of the timeless instrumental “Green Onions,” explaining how the song works from a music theory standpoint. It’s a little like watching Albert Einstein sketch out the equations for general relativity on a cocktail napkin.

“The thing that’s so incredible about Booker T. Jones is, he’s quite a quiet guy. Put him in front of a crowd and he’s like, ‘I’m ready!’ But then put him in a more intimate setting, and that’s not his milieu, which I love about performers. So he walked in and he said, ‘Oh, I’m feeling a little bit nervous and shy.’ He looked amazing, that blue suit and the hat, everything styled to perfection. And he said, ‘I’m going to sit at the piano and just start playing. It helps me settle down.’ As we were finishing up our setup, Booker T. Jones — Booker T. Jones! — is giving us a private concert. You’re trying to act like it’s very normal and not to go full fan-girl on him, just like, ‘How is this happening?’ The cameraman is like, ‘The light’s going to go here?’ And we’re like, ‘The guy is doing his thing RIGHT NOW.’

“Finally, I said, ‘[‘Green Onions’], it’s such a classic, that song. Since the process of working in Stax was so spontaneous, it could feel like things just kind of emerged out of nothing, give it to me. What’s the thought process? How do you get to this song?’ He was already at the piano, and he just started explaining it. It’s hands down one of my favorite scenes in the whole series. … Once you understand how ‘Green Onions’ came about, do you really need a famous person to talk about how much they love that song?”

The fact that Stax soul was chronically underappreciated by both the music industry and music press is a recurring theme in the series. In the intro, Parker promises to tell uncomfortable truths about how the powers-that-be never really wanted the company to succeed. The racial discrimination of the Jim Crow-era South is never far from the surface of the story, such as the time the label’s first breakout star, Carla Thomas, had to ride the service elevator to get to a meeting with the head of Atlantic Records.

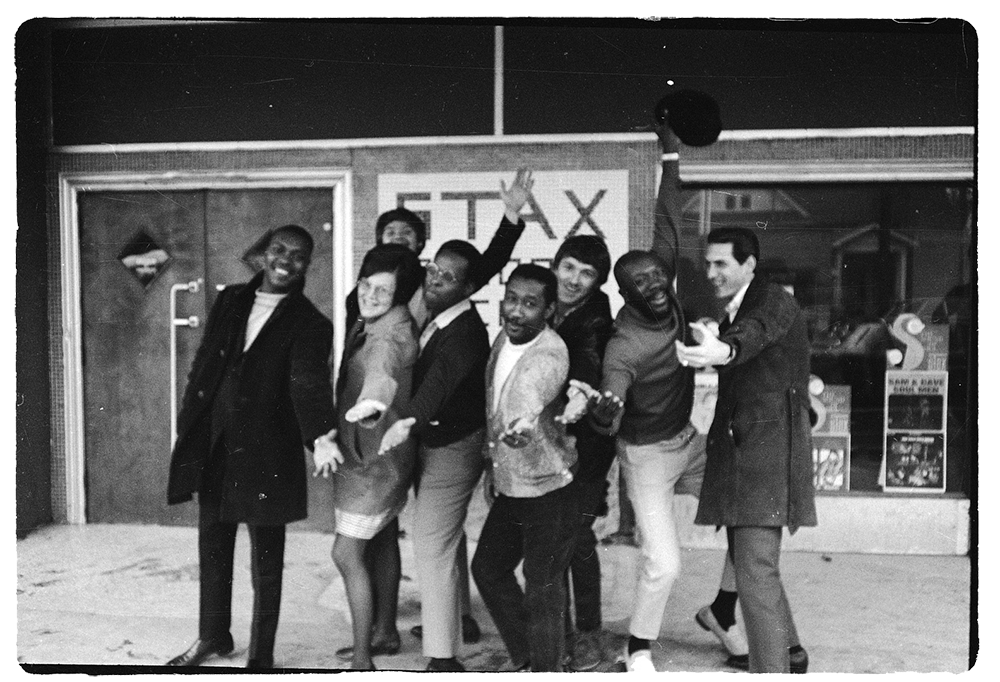

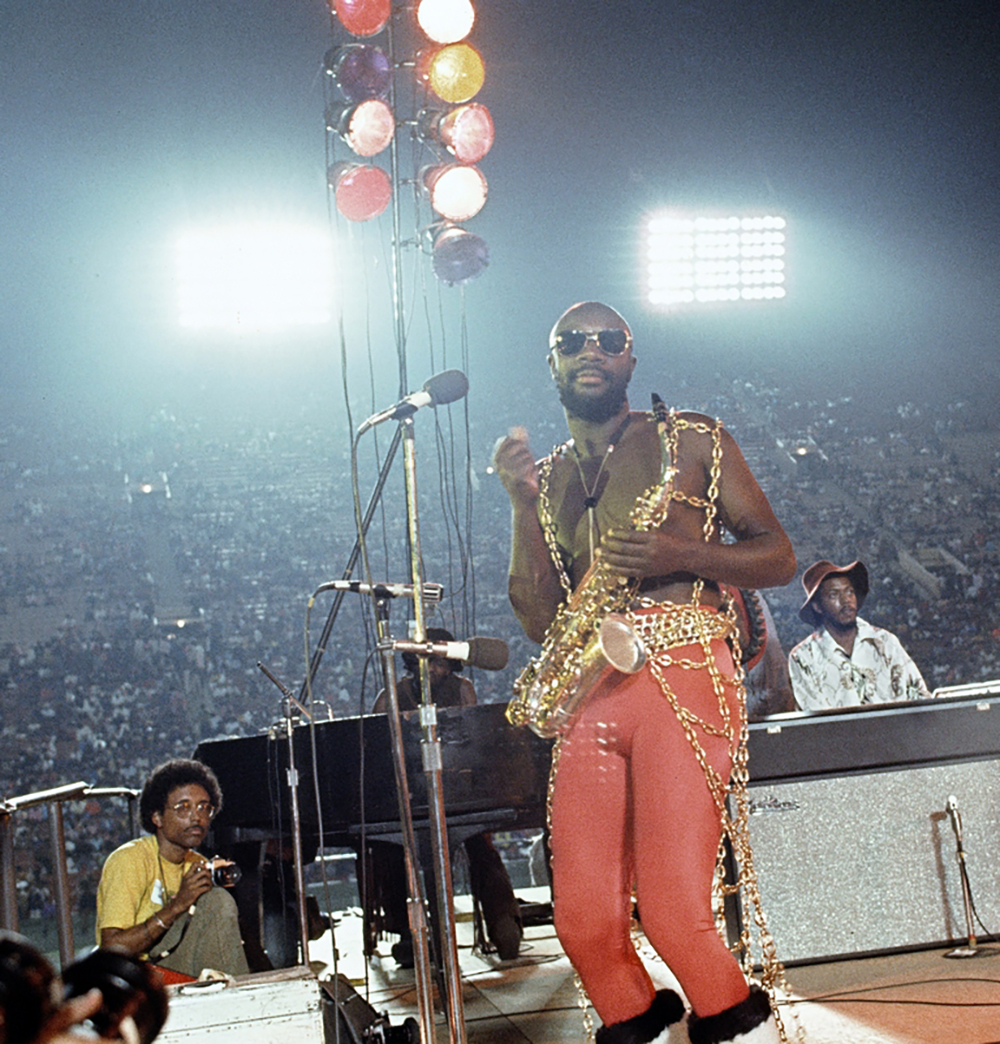

It wasn’t until the Stax/Volt Revue toured Europe in the spring of 1967 that the Black musicians realized what it was like to be respected for their music, and not judged for the color of their skin. The segment of “’Cause I Love You” documenting the tour is powerful, says David Porter. “You could see a little bit of it, as an artist looking at the film, but to be there and to see that energy and that spirit was all over that space. There were people who were enjoying that music just breaking down and crying, getting tremendously emotional when they looked at Otis Redding, or Sam & Dave, or Eddie Floyd. It was something to see.”

Sam Moore acts as an informal narrator for the story of the tour, as you see his younger version hyping up a crowd of Norwegian teens. “There’s so many different films that have been able to make use of this material,” says Wignot. “Thank God it exists, but I was thinking, how do you take something that’s been often seen and give it a new life, a new kind of vitality? … When Sam Moore started talking about his love of the church, I wanted to get that in there, but not the way it is often told, up front. That’s the story of how R&B came together, in a way. It’s so central to what moves him as an artist. We have him talking about the power of the preacher to communicate. I just love in documentaries when you see somebody thinking. Then he says, ‘I would do anything to get that crowd to do a show with me.’ And that is so powerful because he’s not just trying to ‘turn them on.’ Even there, there’s a collective exchange, ‘Come with me, let’s do this together. …’

“The challenge of scenes like that, is how do you do it so that the music gets to live, so that we experience it as viewers as if we were there in the concert? But you’re adding just enough commentary that you’re not speaking on top of the scene, and you’re communicating what was going on emotionally for the performer. So there’s a real balance of too much dialogue versus too little dialogue, and understanding that the material is incredible in and of itself.”

“Chapter One” ends on the high note of the tour, says Wignot. “Episode one builds the way that ‘Try a Little Tenderness’ builds as a song. It was informed by Jim Stewart saying he thinks that that’s the song that best sums up the kind of spirit of Stax. It’s collaboration. It starts with one thing and then another thing gets laid on top and another. It just kind of builds over time and then becomes this big, explosive powerhouse climax of a song.”

“As you go forward with each of these segments, you’re gonna find that it is gonna get heavy. It’s gonna get fun, it’s gonna get powerful because it is alive,” says Porter. “The camaraderie that was between us, enjoying it, was shown in this film. It was a different time, and not a sweet time. We applauded what Jim [Stewart] was doing, giving us the freedom to go into the studio and do that. Everybody worked together in such a cohesive way, and there was a love and magic that happened in a continual way from day to day, hour to hour, all the way to the midnight hour. All that we would do, we’d have fun doing it. Because music is never good unless you can feel the joy inside of doing it.”

Stax: Soulsville U.S.A. is now streaming on Max.

Christen Hill

Christen Hill  Hutchinsphoto | Dreamstime.com

Hutchinsphoto | Dreamstime.com

HBO

HBO