Harold Byrd, suited up to the nines, his mane of gone-white hair crowning his tanned, smiling face, is being hit on by two matrons who recognize him from the Bank of Bartlett commercials which he, the bank’s president, is spokesman for. The three of them are standing in line at Piccadilly cafeteria on Poplar near Highland, waiting to pay their lunch checks.

“Oh, he looks just like he does on television,” coos one of the women, while the other nods with what is either real or mock mournfulness. “And his wife came and took him away from us! Isn’t that a shame?”

At 56, Byrd is unmarried, but he does not correct this misapprehension. He merely keeps the smile on — the characteristically toothy one which, together with his quite evident fitness, a product of daily runs and workouts, makes him look younger than his age — and says, “Thank you.”

Later, as he is leaving the restaurant, Byrd observes, with evident sincerity, “They made my day.” And just in case his companion might have missed it, he notes with a wink the greeting he got from another, younger woman.

All this attention and well-wishing has to be a welcome consolation for Byrd, given the predicament he now finds himself in: Horatio at the Gate against what he sees as Mayor Willie Herenton’s expensive and ill-conceived scheme to develop the Fairgrounds, with a brand-new football stadium as the pièce de résistance.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Byrd is on a mission to demonstrate that a better solution is at hand, one long overdue — namely, the long-deferred construction of a quality football stadium on campus at the University of Memphis, one which he says would cost no more than $100 million, as against the vaguely calculated sums, ranging from $125 million upwards, associated with the mayor’s plan.

Byrd is more than just another citizen with an opinion. He is a member of the university’s Board of Visitors, he is a former president of its Alumni Association, and he was the first president of the Tiger Scholarship Fund. More than all of that, Byrd — the holder himself of undergraduate and graduate degrees from the University of Memphis — has been, for decades now, one of the best-known public faces associated with university causes, athletic and otherwise.

His annual bank-sponsored pre-game buffets, held at the Fairgrounds before every Tiger home opener, draw huge crowds, teeming with the high and mighty and hoi polloi alike. He is either the host or the featured speaker at literally scores of university-related occasions each year, and there is no such thing as a fund-raising campaign for the university in which he does not figure largely.

Byrd’s prominence on the University of Memphis booster scene rivals that of athletic director R.C. Johnson or U of M president Shirley Raines and precedes the coming of either.

It must be painful, Byrd’s companion suggests, as they head for an on-campus tour of the site Byrd favors for a new stadium, that he now finds himself somewhat at loggerheads with both of these figures.

He agrees. He expresses what sounds like sincere regret that he doesn’t have the kind of impressively remote bearing that he associates with a variety of other civic figures — cases in point being Michael Rose, the longtime local entrepreneur and new chairman of First Tennessee Bank, and Otis Sanford, editorial director of The Commercial Appeal.

“I wish I could play my cards closer to the vest,” he laments. “I guess I’m too Clintonesque. I tell everybody everything!”

Byrd admits, “I may make people nervous,” but, as he says, by way of reminding both himself and his companion, “I think people are still talking to me, I think people still like me.”

Byrd is doubtless correct in that assumption, though there is no doubting that he does, in fact, “make people nervous” — and will continue to, so long as Athletic Director Johnson maintains his public stance of support for a Fairgrounds stadium (one, however, as Byrd notes, that has undergone some modification of late) and President Raines keeps her cautious distance from any particular proposal.

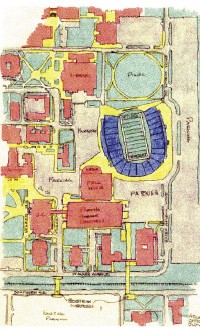

Harold Byrd’s diagram of his preferred site for an on-campus football stadium at the University of Memphis. All facilities are shown as they currently exist except for the stadium itself, which would occupy an expanse now filled by four dormitories all due for demolition, according to U of M officials.

At a recent meeting of the university Board of Visitors, Byrd laid out his vision for an on-campus arena — specifying no less than five acceptable sites.

Site Number One, which Byrd prefers, is a terrain adjoining Zach Curlin Drive on the eastern fringe of the university’s main campus. It would stretch from an open parkland in the vicinity of the Ned R. McWherter Library on the north down to the area of the old University Fieldhouse on the south. As Byrd notes, four dormitory buildings which now occupy the land are shortly to be razed.

“There’s our Grove!” he says excitedly of the available open expanse near the library — evoking the pre-game gatherings of fans on the campus of the University of Mississippi before games at the school’s on-campus Vaught-Hemingway Stadium.

Site Number Two, “which I like almost as much,” Byrd says, is a roomy area along Southern Avenue south of the university’s main administration buildings. Adjacent to an existing athletic complex and athletic dorms, the area consists mainly of parking lots right now.

Site Number Three is the large area that stretches from Patterson west to Highland and northward to Central. “The university owns most of the houses in this area,” says Byrd, and a tour of the zone indicates that, just as he says, most of the edifices, some now used as fraternity houses, many rented out to students, have seen their better days.

Site Number Four is the area just north of Central, partially university-owned, partially requiring some eminent-domain clearance. “I think that one would be more complicated,” Byrd says, though he notes that other university figures, who for the moment are keeping their own counsel, are more keen on it.

And Site Number Five, lastly, is the relatively sprawling area of the university’s South Campus, bordered on the north by Park Avenue. “That wouldn’t be as good as one located directly on the main campus, where most of the students are, but even it would be better by far than the Liberty Bowl.”

Byrd’s enthusiasm for the on-campus sites — especially for the Zach Curlin Drive alternative — is somewhat contagious, but when he made two elaborate presentations recently, one to a meeting of the Board of Visitors, another to an alumni group, there were few among his hearers who were willing to put themselves on the line as being in agreement with him.

“But you wouldn’t believe how many people came up to me afterward and said they thought I had the right idea,” Byrd says. He provides a list of influential people, both on and off campus. “I have no right to speak in their name,” he says, but they are likely to concur.

The first two contacted are much as advertised. Lawyer Jim Strickland, a member of the university alumni group who has launched a campaign for the City Council, is almost as keen on the Zach Curlin site as Byrd is, and Jim Phillips, president of the biometric firm Luminetx, takes time out from a meeting of his board to extol Byrd’s thinking in general terms.

At a recent gathering, prominent developer Henry Turley and University of Memphis professor David Acey were in conversation and were asked what they thought of Byrd’s proposals. “He’s passionate!” Turley exclaimed appreciatively, but the developer, who has interests of his own in the university, wondered where the money would come from. Acey’s concern had to do with space.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Apprised of this, Byrd noted that the same objections might apply, to greater or lesser degree, to the Fairgrounds site, and he insisted that better solutions were at hand at the university once people began to join him in thinking in that direction. Only a dearth of leadership has kept that from happening so far, Byrd says.

Byrd expresses admiration for both Herenton and his Shelby County mayoral counterpart, A C Wharton, though he finds the former figure a bit imperious and the latter one inclined to be more a “moderator” than a leader per se. He still hopes that both can be converted to a vision something like his own for a regeneration of the university campus that becomes the springboard for progress in the community at large.

“Every other university in the state has on-campus football and basketball sites,” Byrd notes, and he reels off a list of universities in the nation that have in the last few years constructed such facilities: “Louisville, Connecticut, Missouri, Central Florida, Florida Atlantic, North Texas, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, Minnesota, Gonzaga … Those are just a few. There have to be 20 or more of them. Have we done it right or has everybody else done it wrong?”

It is the experience of the University of Louisville, in particular, that most animates Byrd. As he points out, that school had, until a generation ago, been primarily an urban-based commuter school with an athletic reputation in basketball. As Memphis fans well know, in fact, the Louisville Cardinals were the basketball Tigers’ chief rivals until recently — when they left Conference-USA for richer pickings in the more prestigious Big East conference, where the Cardinals now figure as a power in both basketball and football.

And there, Byrd contends, but for the aforesaid lack of vision on the part of university and civic officials, would have gone the Tigers and their supporters and the larger community served by the university. As Byrd sees it, Louisville launched its Great Leap Forward in 1992 when Howard Schellenberger became football coach and declared that his goal was for Louisville to play for a national championship.

“For $63 million — that’s all — they built a 40,000-seat stadium on campus. It replaced an old one several miles away, kind of like the Liberty Bowl. They’ve just made a quantum leap, and now they do contend for the national championship!”

How much would it cost for the University of Memphis to build a facility that might lead to the same result? Byrd reflects. “As a banker, I contend that we could build a first-rate collegiate stadium seating something like 50,000 people on campus for $100 million.” He contrasts that figure to estimates as high as $150 million for the facility Mayor Herenton envisions for the Fairgrounds.

And how would an on-campus stadium be financed?

Obligingly, Byrd does the arithmetic. There will be so much for naming rights (à la Louisville’s Papa John’s Stadium or, for that matter, FedExForum). So much from student fees. (“They’re building a new $45 million University Center right now on the basis of a modest increase in student tuition,” Byrd says. “Don’t you think students would be totally excited to walk to an on-campus facility? And our fees would still be the lowest in the state.”) So much from signage and from sale of suites and from organized fund-raising campaigns of the sort Byrd is a seasoned veteran of.

The problem, as Byrd sees it, is that the university has historically let itself get sidetracked from the clear and evident duty of completing its on-campus presence, which is what the fact of self-contained athletic facilities would amount to. Memphis’ state-supported university, he notes again, is the only facility in Tennessee so deprived.

With some chagrin, he acknowledges that he himself, both as chairman of the Shelby County delegation during his service as a state representative in the 1970s and later as an active university booster, acceded to the series of athletic structures and arenas built elsewhere — the Liberty Bowl (then known as Memorial Stadium) and the Mid-South Coliseum in the mid-’60s and, more reluctantly, the Pyramid downtown.

“Downtown was always the only other location for putting a first-class facility, where there was an infrastructure in place that could profit from it, but the Pyramid was NBA-unacceptable from the inception, and I told them so.”

Byrd sighs. “The leaders of government at that time were fearful of the taxpayers and more worried about that rather than building the facility like it should have been built. The result was that it ended up costing us more rather than less.”

And the irony, Byrd says, is that the university was then, as it would be now under Herenton’s proposed Fairgrounds development, the prime source of revenue support for all these city facilities — up to as much as 90 percent, and 50 percent even for FedExForum, which is totally under the control of the NBA’s Grizzlies.

“Flying into Memphis, you notice the Pyramid, the Liberty Bowl, and the Coliseum,” says Byrd. “They represent over $500 million in today’s dollars if you had to replace those facilities, and they’re all about to be either mothballed or destroyed. They’re not in imminent danger of encountering footballs or basketballs — they’re in danger of the wrecking ball! They must not have been in the right place to begin with if they need to be torn down now.”

Why, then, repeat that error by rebuilding something else new and shiny and expensive, but doomed to obsolescence, at the Fairgrounds? Byrd recalls city councilman Dedrick Brittenum saying, in a discussion about the proposed new venues, that whatever went in at the Fairgrounds should be built to last 30 or 40 years.

“Thirty or 40 years! That’s no time at all. What we need is to create a traditional site — like Neyland Stadium at the University of Tennessee. That goes all the way back to the 1920s!”

Byrd recalls that the old University Fieldhouse, adjacent to his preferred site for a stadium on the eastern edge of the U of M campus, once served as an on-site facility for Tiger basketball games during the period in the late 1950s and early 1960s when the university was coming of age as a national power in that sport. “What if they’d kept on going and expanded it and built a state-of-the-art facility there?”

He acknowledges having signed off as a state legislator on construction of both the Mid-South Coliseum as a replacement for the fieldhouse and the Liberty Bowl.

“If we’d put them in the right place, on campus, 20 million people would have visited that campus in the years since 1965. What would be the effect of having 20 million on the University of Memphis campus during that time?”

He ticks off several imagined consequences — increased donations, an enlarged study body, a developed social-fraternity infrastructure, a better-paid and more prestigious faculty. In short, a big-league university instead of the perpetually hand-to-mouth institution that is the University of Memphis today.

“We’ve got wonderful programs there. A speech and hearing center, a new school of music, a beautiful library.” He lists several other glories of the university, all, he contends, hidden more or less under a bushel. “When I talk to my fellow members of the Board of Visitors or the other university groups I belong to, I ask them, how many times have you actually visited the university when it wasn’t in the line of duty? It’s almost always very seldom or never.”

Byrd is realistic. He knows it’s too late to create a basketball arena on campus. FedExForum, which, as he sees it, has its own virtues, will serve that purpose. But football is another matter. Not only would it have enormous impact on the university itself with eight football dates a year, including the annual Southern Heritage Classic and Liberty Bowl events, plus innumerable concerts. “As a state facility, the stadium would be exempt from all those restrictions the Grizzlies put on other facilities,” he says. “Altogether, we should attract a million people the first year alone.”

As for the surrounding community, says Byrd, “The mayor talks about using tax-increment financing to redevelop the area around the Fairgrounds. Why not use it instead to build up the area around the university? The only thing that’s been built around the Fairgrounds in recent years is Will’s Barbecue, and it closed years ago. There are lots of existing businesses in the university area. They’ve paid their dues, and they deserve the support this would give.”

Like someone reluctantly confiding a secret, Byrd says, “Most people think the university is operating on a plan, but they’re not. They don’t have the kind of Teddy Roosevelt, damn-the-torpedoes, full-speed-ahead outlook that we had under Sonny Humphreys [university president during its major expansion era in the 1950s and 1960s]. We’ve had a dearth of leadership. R.C. and President Raines are waiting on Herenton. They should have their own vision, to get everybody together … .”

He takes a breath and continues:

“If that were allowed to happen, it would be amazing.”

Harold Byrd makes it clear that he is prepared to damn the torpedoes and go full-speed ahead and to keep on recommending, and seeking, that kind of amazement. And, sooner or later, he fully expects to have some serious company in that endeavor.

Greg Cravens

Greg Cravens