The young student knew how far the guidance of a good music teacher could take him. “It was assumed that you would play jazz,” he wrote many years later. “Memphis’s young musicians were to unwaveringly follow the footsteps of Frank Strozier or Charles Lloyd or Joe Dukes in dedicating their lives to the pursuit of excellence.” The young man had a jazz combo with his friend Maurice. “Because he cosigned the loan for the drums, loaned us his car, and believed in us, Maurice and I were both deeply indebted to Mr. Walter Martin, the band director. You could hear a reverence in his voice when he spoke Maurice’s name.”

Yet he gained more than material assistance from his high school education. “I took music theory classes after school. Professor Pender was the choral director at Booker T. Washington, and like the generous band directors, Mr. Pender made an invaluable contribution to my musical understanding.” Pondering his lessons on counterpoint, the student thought, “What if the contrapuntal rules applied to a twelve-bar blues pattern? What if the bottom bass note went up while the top note of the triad went down, like in the Bach fugues and cantatas?” And so, sitting at his mother’s piano, he wrote a song.

He had only just graduated when the piece he composed came in handy. Though it was written on piano, he suddenly found himself, to his amazement, in a recording studio, playing a Hammond M-3 organ. He thought he’d try his contrapuntal blues on this somewhat unfamiliar instrument. Why not?

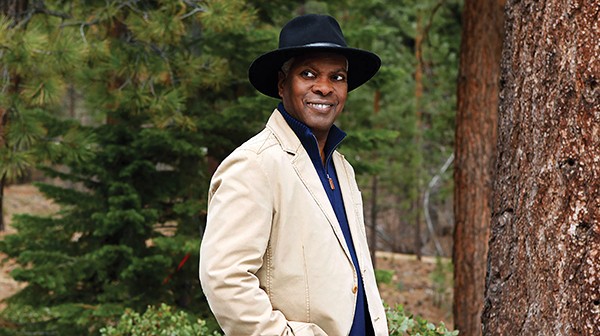

That’s when the magic went down on tape, and ultimately on vinyl. It was an unassuming B-side titled “Green Onions.” To this day, the jazz/blues/classical hybrid that sprung from a teenager’s mind remains a cornerstone of the Memphis sound. The teenager, of course, was Booker T. Jones, co-founder of Booker T. and the MGs. As he reveals in his autobiography, Time is Tight: My Life, Note by Note, his friend, so revered by the band director at Booker T. Washington High School, was Maurice White, future founder of Earth, Wind & Fire. Their lives — and ours — were forever changed by their high school music teachers.

It’s a story worth remembering in these times, when the arts in our schools are endangered species. And yet, while you don’t often hear of band directors cosigning loans or handing out car keys anymore, they remain the unsung heroes of this city’s musical ecosystem. The next Booker T. is already out there, waiting to take center stage, if we can only keep our eyes on the prize.

Mighty Manassas

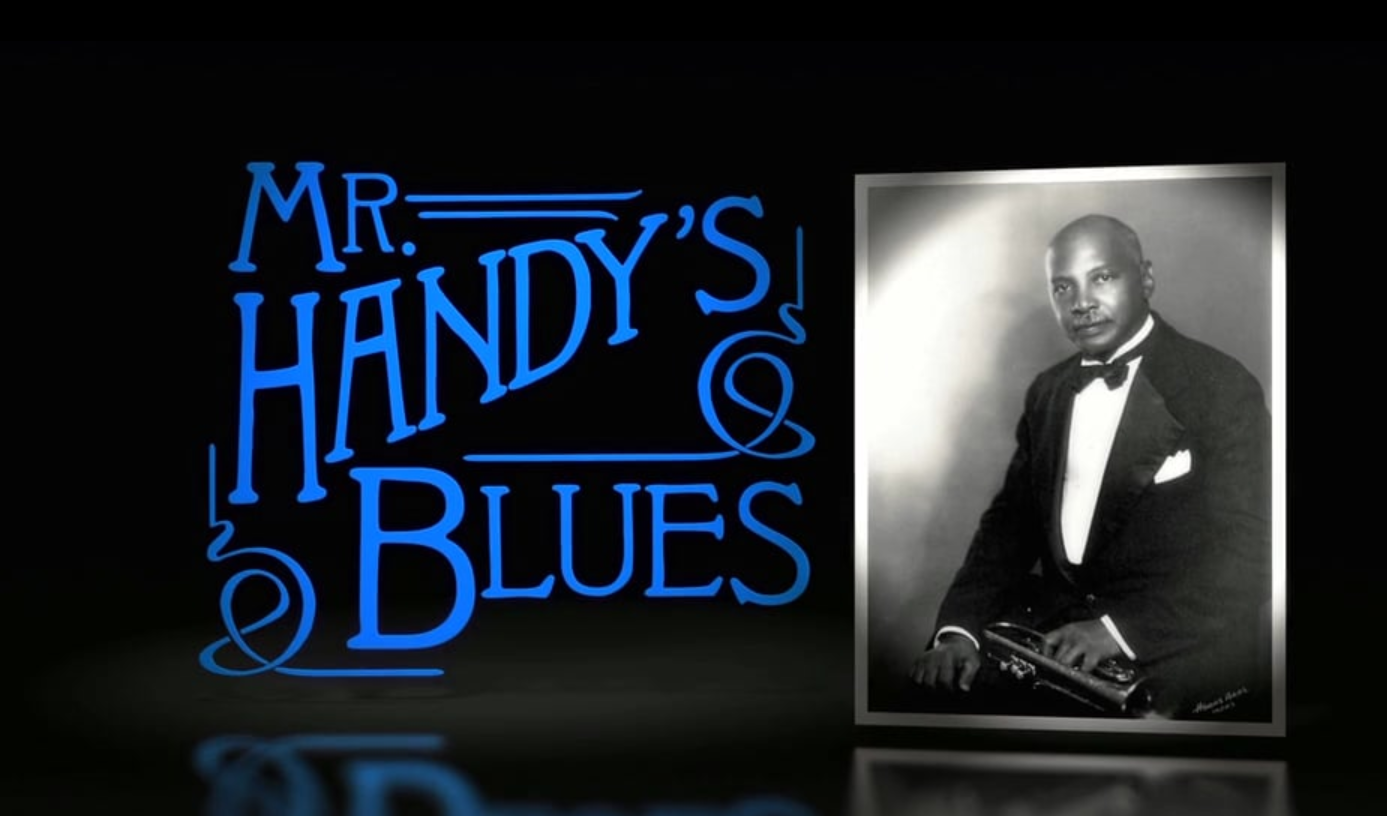

The big bang that caused the Memphis school music universe to spring into being is easy to pinpoint: Manassas High School. That was where, in the mid-1920s, a football coach and English teacher fresh out of college founded the city’s first school band, and, right out of the gate, set the bar incredibly high. The group, called the Chickasaw Syncopators, was known for their distinctive Memphis “bounce.” By 1930, they’d recorded sides for the Victor label, and soon they took the name of their band director: the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra. They released many hit records until Lunceford’s untimely death in 1947.

Nearly a century later, Paul McKinney, a trumpet player and director of student success/alumni relations at the Stax Music Academy (SMA), takes inspiration from Lunceford. “He founded his high school band and took them on the road, with one of the more competitive jazz bands in the world, right there with Count Basie and Duke Ellington. And I’ve tried to play that stuff, as a trumpet player, and it’s really, really hard! And then one of the best band directors in Memphis’ history, after Jimmie Lunceford, was Emerson Able, also at Manassas.”

Under Able and other band directors, the school unleashed another wave of talent in the ’50s and ’60s, a series of virtuosos whose names still dominate jazz. One of them was Charles Lloyd, who says, “I went to Manassas High School where Matthew Garrett was our bandleader. Talk about being in the right place at the right time! We had a band, the Rhythm Bombers, with Mickey Gregory, Gilmore Daniels, Frank Strozier, Harold Mabern, Booker Little, and myself. Booker and I were best friends, we went to the library and studied Bartok scores together. He was a genius. We all looked up to George Coleman, who was a few years older than us — he made sure we practiced.”

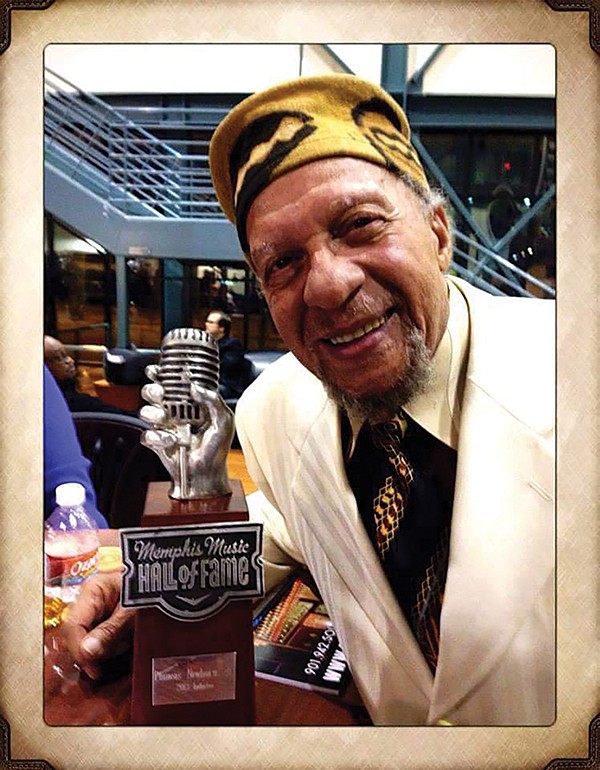

Meanwhile, other talents were emerging across town at Booker T. Washington High School, which spawned such legends as Phineas Newborn Jr. and Herman Green. It’s no surprise that these players from the ’40s and ’50s inspired the next generation, like Booker T. Jones, Maurice White, or, back at Manassas, young Isaac Hayes, yet it wasn’t the stars themselves who taught them, but their music instructors. Although they didn’t hew to the jazz path, they formed the backbone of the Memphis soul sound that still resounds today. As today’s music educators see it, these examples are more than historical curiosities: They offer a blueprint for taking Memphis youth into the future.

Making the Scene

And yet the fact that such giants still walk among us doesn’t do much to make the glory days of the ’30s through the ’60s within reach today. For Paul McKinney, whose father Kurl was a music teacher in the Memphis school system from 1961 to 2002, it might as well be Camelot. And he feels there’s a crucial ingredient missing today: working jazz players. “All the great musicians that came out of Memphis in the ’50s and ’60s were a direct result of the fact that their teachers were so heavily into jazz. The teachers were jazz musicians, too. We teach what we know and love. So think about all those teachers coming out of college in the ’50s. The popular music of the day was jazz! And the teachers were gigging, all of the time.”

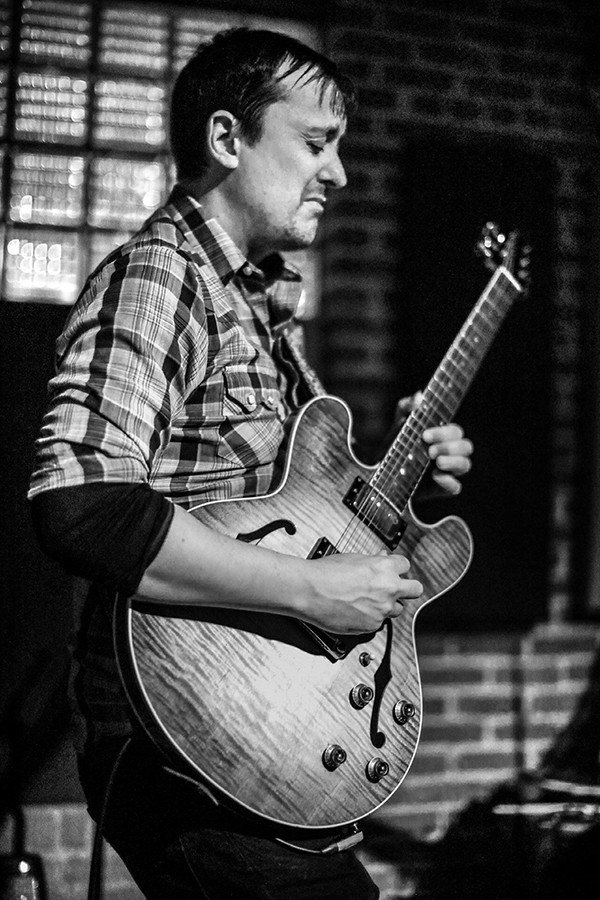

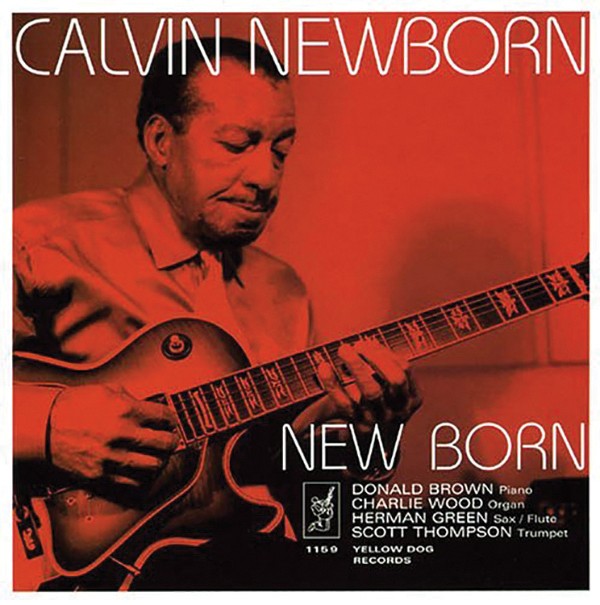

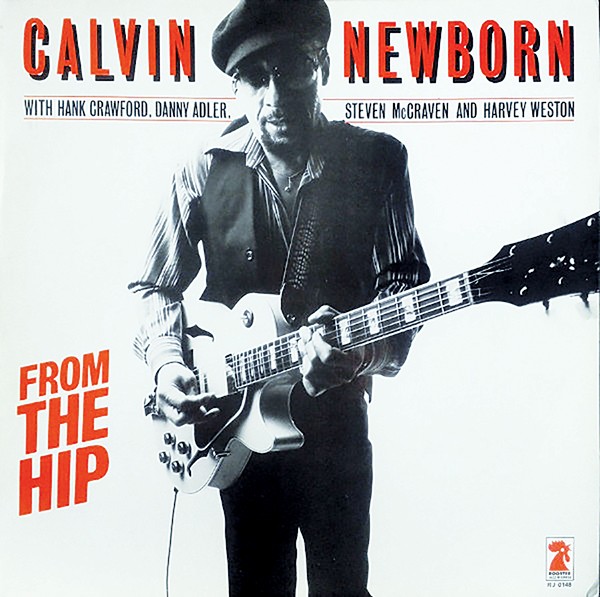

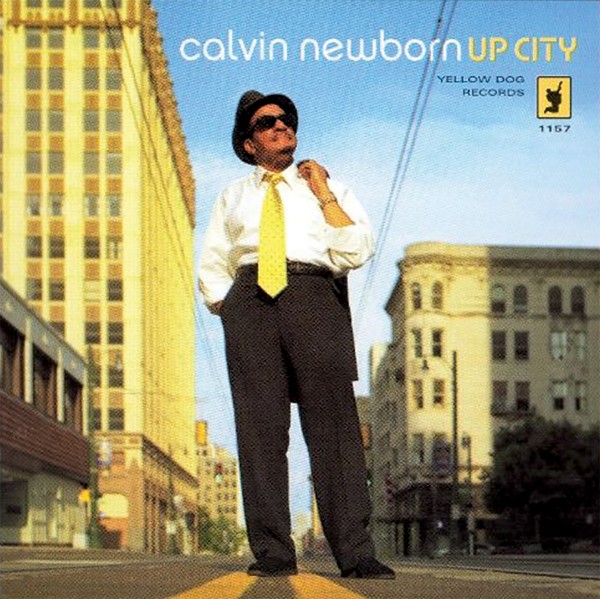

Kurl, for his part, was certainly performing even as he taught (and he still can be heard on the Peabody Hotel’s piano, Monday and Tuesday evenings). “Calvin Newborn played guitar with my and Alfred Rudd’s band for a number of years,” he recalls. “We played around Memphis and the surrounding areas.” That in turn, his son points out, brought the students closer to the world of actual gigs, and accelerated their growth. In today’s music departments, Paul says, “there are not nearly as many teachers who are jazz musicians. As a jazz trumpeter and a guy who grew up watching great jazz musicians, that’s what I see. Are there a few band directors who play it professionally? Yes. But there aren’t many.

Trombonist Victor Sawyer works with SMA but also oversees music educators for the Memphis Music Initiative (MMI). Both nonprofits, not to mention the Memphis Jazz Workshop, have helped to supplement and support public music programs in their own ways — SMA by hosting after school classes grounded in local soul music, MMI by helping public school teachers with visiting fellows who can also give lessons. Sawyer tends to agree that one important quality of music departments past was that the teachers were working jazz musicians. “All these people from the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s, and before have stories of going to Beale Street and checking out music and having the opportunity to sit in. I feel like the high schools in town today aren’t as overtly and intentionally connected to the music scene. So you’re not really seeing the pipelines that you did. When you don’t have adults who will say, ‘Come sit in with me, come see this show,’ you lose that natural connectivity. So you hear in a lot of these classes, ‘You can’t do nothing in Memphis. I’ve got to get out of Memphis when I graduate.’ That didn’t used to be the mindset because the work was here, and it still is here; it’s just not as overt if you don’t know where to look.”

Music Departments by the Numbers

A sense of lost glory days can easily arise when discussing public education generally, as funding priorities have shifted away from the arts. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities calls the years after the 2008 recession “a punishing decade for school funding,” and Sawyer contrasts the past several decades with the priorities of a bygone time. “After World War II, there was a huge emphasis on the arts. Every city had a museum and a symphony. Then, people start taking it for granted, and suddenly you have all these symphonies and museums that are struggling. The same for schools: There’s less funding. When STEM takes over, arts funding goes down. The funding that the National Endowment of the Arts provides for schools has gone down dramatically.”

Simultaneously, the demographics of the city were shifting. “Booker T. Washington [BTW], Hamilton, Manassas, Douglass, Melrose, Carver, and Lester were the only Black high schools in the late ’50s/early ’60s. So of course people gathered there,” Sawyer says. “You’d have these very tight-knit cultures. Across time, though, things became more zoned; people became more spread out. Now things are more diffuse.”

Not only did funding dry up, enrollment numbers decreased for the most celebrated music high schools. Dru Davison, Shelby County Schools’ fine arts adviser, points out that once people leave a neighborhood, there’s not much a school principal can do. “What we’ve seen at BTW is a number of intersecting policies — local, state, and federal — that have changed the number of students in the community. And that has a big impact on the way music programs can flourish. And more recently, it’s been an incredibly difficult couple of years because of the pandemic. Our band director at Manassas, James McLeod, passed away this year. So we’re working to get that staff back up again, but the pandemic has had its toll on the programs.”

Davison further explains: “The number of the kids at the school determines the number of teachers that can work at that school. So at large schools like Whitehaven or Central, that means there are two band directors, a choir director — fully staffed. But if you go to a much smaller school, like BTW and Manassas, the number of students they have at the schools makes it difficult to support the same number of music positions. That’s a principal’s decision.”

The Culture of the Band Room

Even if music programs are brought back, the disruption takes its toll. One secret to the success of Manassas was the through-line of teachers from Lunceford to Able to Garrett and beyond. Which highlights a little recognized facet of education, what Sawyer calls the culture of the classroom. “When you watch Ollie Liddell at Central High School or Adrian Maclin at Cordova High School, it’s like, ‘Whoa! Is this magic?’ These kids come in, they’re practicing, they know how to warm up on their own. But it’s not magic. These are master-level teachers who have worked very hard at classroom culture. The schools with the most thriving programs have veteran teachers who have been there a while, so they have built up that culture.”

In fact, according to Davison, that band room culture is one reason music education is so valuable, regardless of whether or not the students go on to be musicians. “I’m just trying to help our teachers to use the power of music to become a beacon of what it means to have social and emotional support in place. As much as our music teachers are instilling the skills it takes to perform at a really high level, they’re also creating places for kids to belong. That’s been something I’ve been really pleased to see through the pandemic, even when we went virtual.” Thus, while Davison values the “synergy” between nonprofits like SMA or MMI and public school teachers, he sees the latter as absolutely necessary. “We want principals to understand how seriously the district takes music. It’s not only to help students graduate on time but to create students who will help energize our community with creativity and vision.”

And make no mistake, the music programs in Memphis high schools that are thriving are world-class. By way of example, Davison introduces me to Kellen Christian, band director at Whitehaven High School, where enrollment has remained reliably large. With a marching band specializing in the flashy “show” style of marching (as opposed to the more staid “corps” style), Whitehaven has won the High Stepping Nationals competition four times. (Central has won it twice in recent years.) Hearing them play at a recruiting rally last week, I could see and hear why: The precision and power of the playing was stunning, even with the band seated. Christian sees that as a direct result of his band room culture. “Once you have a student,” he says, “you have to build them up, not making them feel that they’re being left out. So we’re not just building band members; we’re building good citizens. They learn discipline and structure in the band room. That’s one of the biggest parts of being in the band: the military orientation that the band has.”

Lured into Myriad Musics

But Christian, a trumpeter, is still a musician first and foremost, and he sees the marching band as a way to lure students into deeper music. “Marching band is the draw for a lot of students,” he says. “When you see advertisements for bands from a school, you don’t see their concert band, you don’t see their jazz bands. The marching bands are the visual icons. It’s what’s always in the public eye.” But ultimately, he emphasizes, “I love jazz, and marching band is the bait. You’ve got to use what these students like to get them in and teach them to love their instrument. Then you start giving them the nourishment.”

As Sawyer points out, that deeper nourishment may not even look like jazz. “Even with rappers, you’ll find out they knew a little bit about music. 8Ball & MJG were totally in band. NLE Choppa. Drumma Boy’s dad is [retired University of Memphis professor of clarinet] James Gholson!” Even as Shelby County Schools is on the cutting edge of offering classes in “media arts” and music production, a grounding in classic musicianship can also feed into modern domains. True, there are plenty of traditional instrumentalists parlaying their high school education into music careers, like David Parks, who now plays bass for Grammy-winner Ledisi and eagerly acknowledges the training he received at Overton High School. But rap and trap artists can be just as quick to honor their roots. “Young Dolph, rest in peace, donated to Hamilton High School every year because that’s where he went,” notes Sawyer. “Anybody can do that. Find out more about your local school, and donate!”

Reminiscing about his lifetime of teaching music in Memphis public schools, Kurl McKinney laughs with his son about one student in particular. “Courtney Harris was a drummer for me at Lincoln Junior High School. He’s done very well now. Once, he said, ‘Mr. McKinney, I’ve got some tapes in my pocket. Why don’t you play ’em?’ I said, ‘What, you trying to get me fired? All that cussin’ on that tape, I can’t play that! No way! I’m gonna keep my job. You go on home and play it to your mama.’

“But I had him come down to see my class, and when he came walking in, their eyes got as big as teacups. I said, ‘Class, this is Gangsta Blac. Mr. Gangsta Blac, say something to my class.’ So he looked them over and said, ‘If it hadn’t been for Mr. McKinney, I would never have been in music.’” Even over the phone, you can hear the former band director smile.

courtesy Ditto Taylor

courtesy Ditto Taylor  courtesy Ditto Taylor

courtesy Ditto Taylor  Shawn M. Carter

Shawn M. Carter  courtesy Ditto Taylor

courtesy Ditto Taylor  Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon  Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon  Courtesy Ed Finney

Courtesy Ed Finney  Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon  Courtesy Stephen Lee

Courtesy Stephen Lee  Christian Patterson

Christian Patterson  Photo Courtesy of Jadene King

Photo Courtesy of Jadene King  Photo Courtesy of Jadene King

Photo Courtesy of Jadene King  Steve Roberts

Steve Roberts

Mike Brown

Mike Brown  Photo Courtesy of Jadene King

Photo Courtesy of Jadene King  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Richard Dumas

Richard Dumas  Stephen Sweet

Stephen Sweet