Imagine being born into the Great Depression, growing up in South Memphis. You’re a part of the household of the Reverend Tigner Green. You’re not terribly wealthy, but you’re better off than many and not without some dignity in the racist order that prevails in the 1930s South.

Your life is filled with music. Your biological father, Herman Washington — murdered when you were only two — once played in W.C. Handy’s legendary band. You bear his name, and they call you Junior. Your grandmother was a pianist of some talent in St. Louis, and as you mature, you develop skills in piano and guitar. Under your stepfather’s guidance at the Church of God in Christ, you play guitar alongside a blind pianist, Lindell Woodson, marveling at a dexterity rivaling that of the great Art Tatum, with songs bringing congregations to their feet, clapping and shouting.

Every day hinges on three simple tasks: You kill a chicken; you chop wood; and you practice your music lessons.

“That,” says Herman Green, the man recalling all this, “is one part of the beginning of yours truly.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Dr. Herman Green, who would come to carry the genius of post-war blues, soul, and jazz into the 21st century, halts this idyllic tale of youth as he confronts a defining moment: high school marching band. “They didn’t have marching band in elementary school,” remembers Green. “So I got in high school, and I told my mom, ‘I gotta get me a horn. I can’t march down the street with a guitar; they won’t even let me!’ She said, ‘Okay, we’ll get down there and get you a horn. What kind do you wanna play?'”

Though trumpet looked easy enough, its demands on his lips were baffling, so Green settled on alto saxophone. The rest is history, thanks in no small part to his mother, Alice Lee, and the stepfather whose surname he would ultimately take as his own.

Life at Booker T. Washington High School would bring with it more than just a change of instrument. It was there that Green met a man who seemingly presided over every period of Memphis musical innovation. One wouldn’t be far off imagining some demi-god descending to usher young Herman into the world of secular music — a demi-god doing the funky chicken.

“There were pageants we used to do at the end of the school season at Booker T. Washington, and Rufus Thomas was the one that put it together. So we did that, I did that for four years while I was in high school, with him. Plus, I played gigs with him.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Herman Green

By the age of 15, Green was in the orchestra backing talent shows that Rufus Thomas and his colleague “Bones” compèred on Beale Street. Over the next couple years, the music he played became more worldly, culminating in the arrival of another pivotal figure. “B.B. King came to Memphis from Mississippi, so Rufus said, ‘I got a saxophone player you need. His name is Herman Green.’ So we got to playing like Covington, Dyersburg, West Memphis; we played the Harlem Club, which was a black club. They was over there rolling the dice while we was over in the corner playing.

“So we did that for about a year, and I said, ‘B., you think you ready to move? What you wanna do, you wanna stick around here, or you wanna go further?’ He said, ‘Well, I think we need to move. We goin’ to Kansas City. I heard they love the blues there.’ So we went up there, me and B., to look it over. And there was a lot of jazz musicians there in Kansas City. I said, ‘Okay, B., I don’t hear nobody blowin’ no blues. Let me get on the bandstand,’ ’cause I could play some jazz myself then. I mean, I was taught early. And guess who it was I jumped on the bandstand on top of — Charlie Parker! Now, you know I had to be a fool to get on the bandstand with Charlie Parker there. But at that time I hadn’t seen Charlie Parker in my life, man! So Charlie said, ‘Hey, you play good for a kid.'”

Green and King returned to Memphis as planned, but other temptations awaited. At the Memphis Cotton Carnival, a touring troupe offered work. “They had a show with girls running out there with their shorts and dancing. They called it a ‘bally’ stage. Pay your money, come inside. I did 22 shows in 8 hours. They were paying $5 — that’s what a musician was making in those days. And the bally troupe wanted me to go with them with the show. So I left a note to tell my folks I was going to leave, and I’ll let you know where I’m going and I’ll be in touch, and blah, blah, blah. … I was ready to leave, because they were headed to Canada, all the way up the east coast.

Dave Gonsalves , Herman Green, John Coltrane, and Arthur Hoyle

“Man, I’m up there playing my butt off, and all of a sudden … Well, my mom was a church mother, and she wasn’t supposed to be seen in those kind of places, you know. But she came through them curtains, man, and she stood there like this with her arms crossed. And she waited till the end of the show. She was a classy lady. Then she said, ‘Junior, I got your note. I didn’t come up here to scold you. I didn’t come up here to hurt you. I came up here to keep you here, because you’ve got a little more schooling to do. You need to know a little more about life. Now come on. Your daddy’s downstairs waiting on ya.’

“That was my stepfather. He was in the car. And preachers then, you know, had them big, long limousines. And I just said ‘Well, there’s no use arguing here. I just might as well go.’ So I did, I went home and stayed a whole year. And I lost a brand new pair of suede shoes that I bought at Florsheim. Thirty dollar shoes! I left ’em on the bus, man. But they really were concerned about me getting an education. They wanted me to go to college.

“So I went one year. Then next time that bally troupe came back, I played a gig with ’em, and I said, ‘What time y’all planning on leaving town?'” With his mother’s blessing, this time, Green left Memphis.

“I went all the way up to Toronto, Canada, man, and come on back down, and when they headed back down to Virginia, I got off in Washington, D.C., and I went back to New York, and that’s when I got in touch with Sonny Stitt and Gene Ammons and John Coltrane. I was like 21; they at that time were 27 or 28 I think.”

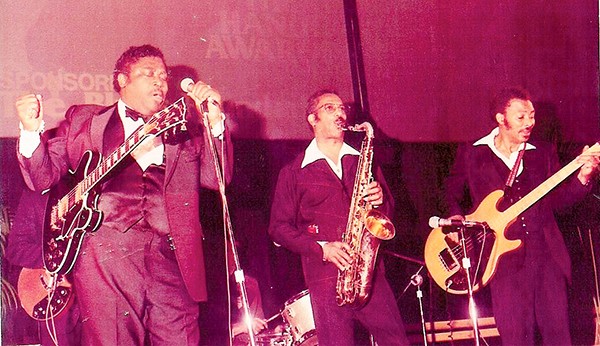

BB King, Herman Green, and Melvin Lee

“When I first got to New York, I picked up the paper and it said Jam Session: Birdland. Sonny Stitt was booked there for three weeks with Art Blakey, but they had a jam session on Sundays before they’d do the show. I took the paper, stuck it under my arm, grabbed my horn and went down there. Got there, slammed my horn down on the table, took it out, and walked up on the stage. So Sonny, he kinda looked at me funny, and he thought, ‘Well here’s something.’ That’s what he told me later that he said to himself.

He said, ‘Where you from?’ I said, ‘Memphis Tennessee.’ ‘That explains what you just did,’ he said. ‘Well let this be a lesson. Don’t never walk on nobody’s bandstand until they call you. And you let ’em know who you are.’ And then he said ‘Now let’s get back up there and play, ’cause you can play.’”

It so often came down to that simple fact for Herman Green: He had chops. That skill served him well wherever he landed, including the heady New York bop scene of 1950.

Back in Memphis, he played on Rufus Thomas’ “Why Did Ya Dee-Gee?” — released on Chess Records and Sun Records. He was drafted into front line service for the Korean War, only to be reassigned to the Army band when officers heard him practicing his horn. Upon his return to the States, a layover in San Francisco turned into a two-year stint: “I loved that city,” he remembers. There he played Bop City and led the house band at the Blackhawk, a pivotal club where he played with pioneers of the West Coast Sound like Dave Brubeck, as well as his New York cohorts: Miles Davis, Thelonius Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, and John Coltrane. Occasionally, he’d even see his old Memphis friend Phineas Newborn Jr. when he passed through.

Finally, Green moved on, landing a steady gig with Lionel Hampton and His Orchestra, which he stuck with for 10 years. (You can hear the 1960 band on the CD, Live at the Metropole, New York City.) It was Hampton, Green says, who had the biggest impact on his playing, but it was at this time, during a three month residency at the Riviera in Las Vegas, that he had a brush with another demi-god who’d impacted all of jazz itself.

(You can hear the 1960 band on the CD, Live at the Metropole, New York City).“They had an after-hours breakfast jazz jam place, and I was over there playing on the stand, and I used to play with my eyes closed ’cause I didn’t wanna get disturbed, especially when I was playing something different. And then I heard this deep voice say ‘Keep on playing, boy!’ And I looked around, and there was Louis Armstrong standing next to me! Ooh, Lord have mercy, I almost put my horn down, man!

“He said, ‘Don’t you dare put that down, the way that you playing.'”

It was Green’s mother, who had given her blessing when he left Memphis, who brought him back. During a session for Atlantic Records in New York, he got a call that his mother wanted him home. She was dying of tuberculosis. He left the session immediately, getting home in time to see her just before she passed. Soon, he was settled again in his hometown. It was 1967, and Stax Records was in full swing. Green, who had played with his younger cousin Al Jackson Jr. on Beale Street, soon fell into recording sessions there. For a while, as the Memphis scene fired on all cylinders, there was plenty of work to be had. In the early 1970s, he married Rose Jackson (who has since passed away), and by mid-decade, he had taken a teaching position at Lemoyne-Owen College. All the while, he played his horn, often with fellow Booker T. Washington alum Calvin Newborn on guitar, mentoring young jazz talents like James Williams along the way.

Even as Beale Street withered after the 1960s, traditional jazz thrived in Memphis for a time. Green and his band, the Green Machine, became a fixture on the scene, and he fondly recalls the rebirth of Beale Street in the 1980s, marked for him personally by the night Stevie Wonder sat in with his band after playing Memphis in May.

In 1986, he befriended a young bass player, Richard Cushing, who saw great possibilities in the jam-based approach of the Grateful Dead. The next year, their friendship bore fruit with FreeWorld, now perhaps the longest-running Memphis band of this generation. The group has consistently brewed an unpredictable blend of funk, New Orleans street music, soul, and jam rock — a gumbo of influences that has led them to carve out a reliable niche on Beale. Even as local audiences for bop-informed, swinging jazz lose the plot, such bands with a backbone of funk keep the spirit of improvisation alive and well. FreeWorld has kept Green spry on the stage, and they were there backing him when he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Memphis College of Art. Seeing FreeWorld play Beale Street recently, I was struck by how crucial the simple act of dancing has been to Memphis music, bridging the many disparate paths Green has taken over decades. Dance weaves like a golden thread from the strut of Rufus Thomas, through the years with Lionel Hampton, the Stax years, and into the present. All the while, Green has mined the more complex territory of harmony and melody embodied in his first chance meeting with Charlie Parker.

Seeing him take the microphone last Sunday, singing a blues song resonating with echoes of old Beale Street, all of his 87 years seemed to be summed up in a few elegant lines, dipping and crosscutting to the rhythm, as he sang into the sky, eyes wide open, “She’s waiting for me, she’s waiting for me.”