A week before Joseph Mitchell’s ex-partner died, he told Mitchell some devastating news: He had been diagnosed with AIDS. A few months later, Mitchell himself tested positive for HIV, the virus responsible for triggering AIDS, and was told by his doctor that he had six months to live.

“My initial response was numbness,” Mitchell recalls. “It was devastating. I pushed it in the back of my head and didn’t really deal with it.” But Mitchell didn’t die within six months. “I didn’t do anything about trying to sustain until about seven years after the diagnosis,” he says.

Mitchell was also a diabetic and had high blood pressure. Those issues, combined with the progression of the HIV virus and his inability to afford antiretroviral treatment were a potentially fatal mixture. And in 2010, he almost died.

“After seven years [living with the virus], high blood pressure, and diabetes was taking a toll on me,” Mitchell says. “It caused me to have some unexpected seizures, which put me into a coma for two-and-a-half weeks. My body literally started breaking down to the point that my kidneys shut down, and I was risking a stroke and a heart attack.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Joseph Mitchell has lived with HIV for 13 years

After waking up from his coma, Mitchell finally came to recognize that seeking treatment was the only way to avoid succumbing to the virus.

Those infected with HIV, human immunodeficiency virus, can have the disease for years before developing symptoms. For some, unfortunately, when they do discover they’ve contracted the virus, it has progressed to its advanced and more life-threatening form: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

More than 635,000 people in the United States have died from the virus; an estimated 36 million people have died globally since the first cases were reported in 1981, according to the World Health Organization.

Mitchell is a member of the group most affected by HIV/AIDS: men who have sex with men (MSM). They account for more than half of all new HIV infections annually and more than half of all people living with HIV in the country, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

African-American MSM — and African Americans as a whole — are at a greater risk of contracting the disease than other groups of people. In 2010, there were an estimated 10,600 new HIV infections among African-American MSM — fewer than the estimated 11,200 new HIV infections among white MSM. It’s an alarming statistic, considering whites make up about 70 percent of the U.S. population, while blacks account for only 14 percent. Black MSM aged 13 to 24 years old have higher rates of new HIV infections than any other MSM subgroup.

“It’s a major problem, but my main concern is making sure that my community understands the importance of knowing your status, protecting yourself and your partner, and being more responsible,” says Mitchell, a peer mentor at Friends For Life, a nonprofit agency that provides assistance to more than 2,000 people living with HIV/AIDS annually. “It does not make me hate the fact that I’m who I am. It doesn’t make me look at other black gay men as the scum of the earth. It just makes me do more to help get these numbers under control,” says Mitchell.

Out of Africa

HIV wasn’t officially diagnosed until 1981. The first U.S. cases were reported in San Francisco and then New York. At the time of its detection in this country, the disease had progressed to its more advanced form, AIDS.

Years before it was detected in the U.S., people were exposed to HIV in Africa. According to Dr. Michael Whitt of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC), HIV-1, one of two types of HIV, is closely related to the SIV illness, originally found in chimpanzees. HIV-1 is responsible for the bulk of HIV infections throughout the world. The other type, HIV-2, is considered less transmittable and primarily prevalent in West Africa.

Whitt, professor and chair of UTHSC’s department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Biochemistry, said the disease was presumably passed into the human population somewhere around the late 1950s or early 1960s.

“The thought is that Cameroon natives would go foraging in the forest to harvest monkeys for food,” Whitt says. “[The theory is] someone came upon a chimpanzee that was infected with the SIV virus and when they went to collect the meat for eating, they may have had a cut or something, and the blood of the monkey got into the cut of the human and it transmitted the virus.”

It’s theorized that multiple people were infected with SIV in Cameroon, which resulted in a variant of the virus being able to replicate in humans. The disease has since spread worldwide. There are more than 35 million people currently living with HIV globally, according to the CDC.

HIV is primarily spread through sexual contact. People can also transmit it through injection-drug use via infected needles and exposure to blood, semen, and other bodily fluids. Initially considered a disease that only affected gay men, the virus has expanded into all genders, subgroups, and races. More than 1.1 million people living with the disease live in the U.S.; about one in six is unaware of their infection. And about 50,000 new HIV infections are recorded in the nation annually.

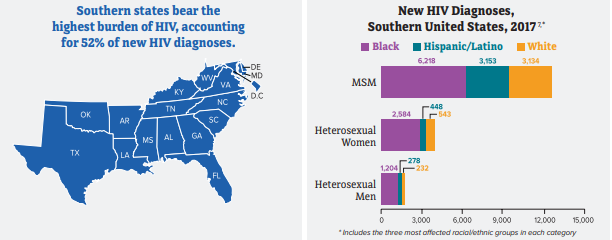

The South: Where HIV Thrives

The southern U.S. is one of the areas most impacted by HIV. In 2010, the CDC released a report saying that metropolitan Memphis had the nation’s fifth-highest proportion of residents newly infected with HIV. The only metropolitan areas with higher rates were Miami, Baton Rouge, New Orleans, and Jackson, Mississippi. The study also disclosed that metropolitan Memphis had the highest proportion of new infections among African-American men between the ages of 15-34.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Dorcas Young (left) and Yvonne Madlock (right)

“We have rates that are higher than we would like to see in this community,” says Yvonne Madlock, director of the Shelby County Health Department. “There has been, and continues to be, an awful lot of effort, energy, thought, and research put into addressing HIV and AIDS on multiple fronts. It is a concern for all of us because it zaps people of quality of life. It zaps us as a community because of the resources that have to be committed to it.”

Madlock says more could be done. “But,” she cautions, “some of that will be done as all of us recognize we have a role to play. Some of our barriers are related to the great stigma that still continues to exist around HIV/AIDS, the lack of understanding of HIV/AIDS, the fear we have around the factors we think are associated with HIV/AIDS, and our reluctance to talk honestly and candidly about sexual health in our community.”

At the end of 2012, about 8,000 people were knowingly living with HIV in metropolitan Memphis; 82 percent of those were black, according to the Health Department.

Sharmain Mayes is among those nearly 6,000 African Americans living with HIV in Memphis. Mayes’ mother was a prostitute and drug addict who unknowingly contracted HIV and became pregnant. Sharmain was diagnosed with HIV when she was just four months old. Years would pass before she was able to comprehend what that truly meant.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Sharmain Mayes with her fiancé, Renrick Winston

“I didn’t really grasp or understand the concept until I was around nine or 10 years old,” Mayes says. “My aunt, who was raising me, was like, ‘You have to be a little bit more careful than the other kids.’ I was like, ‘Okay, that’s fine.’ The way they explained it to me was, ‘it’s something that you give to other people through having sex.’ Of course, at nine or 10 years old, sex was the grossest thing in the world to me. It’s like, ‘I’m not going to be doing that,’ so I wasn’t really worried about anything. It wasn’t until I started telling a few people, and they started treating me different that I started realizing this might be something serious.”

Shelby County and Tennessee

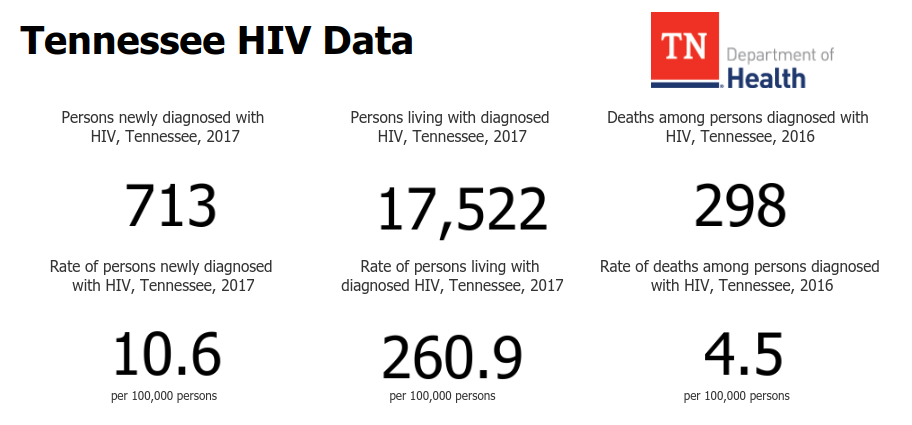

Shelby County accounts for more than 40 percent of all HIV infections in Tennessee, according to the Health Department. In 2012, there were 451 new HIV infections in the Memphis area. In addition to the nearly 8,000 people who have been diagnosed with the disease, the Health Department estimates there are another 2,000 people in Shelby County who are unaware they are HIV-positive.

The area’s high infection rates are attributed to a variety of factors that include lack of awareness, high poverty rates, insufficient health care coverage, cultural stigma, and homelessness.

There are several initiatives and organizations working to assist those infected with HIV/AIDS. The Ryan White Program is the largest federally funded program in the country for people living with HIV/AIDS, providing services to more than 500,000 uninsured or underinsured individuals affected by the virus.

The Shelby County division of the Ryan White Program provides $7 million in funding to 17 different entities to help them combat HIV/AIDS each year. The organizations include Friends For Life, Hope House, the Health Department, and St. Jude Children’s Hospital.

“I think as we’re more aware of the disease and more educated about the disease, we break down barriers and end the stigma of HIV,” says Dorcas Young, the Ryan White Program’s administrator for Shelby County. “When people feel stigmatized and feel like people are in fear of them, they won’t go and get the help that they need. There are a lot of people out there who are HIV-positive, but won’t get care. And it just contradicts all the work that we do. If someone is HIV-positive and they’re in care [and] taking the medicine they need to take, there is less than a four percent chance that they will pass HIV off to their partner. We know that we can essentially prevent HIV if we can get everybody who is positive the treatment they need. But if people are scared to go get treatment, because of what folks are going to say, it’s this terrible cycle.”

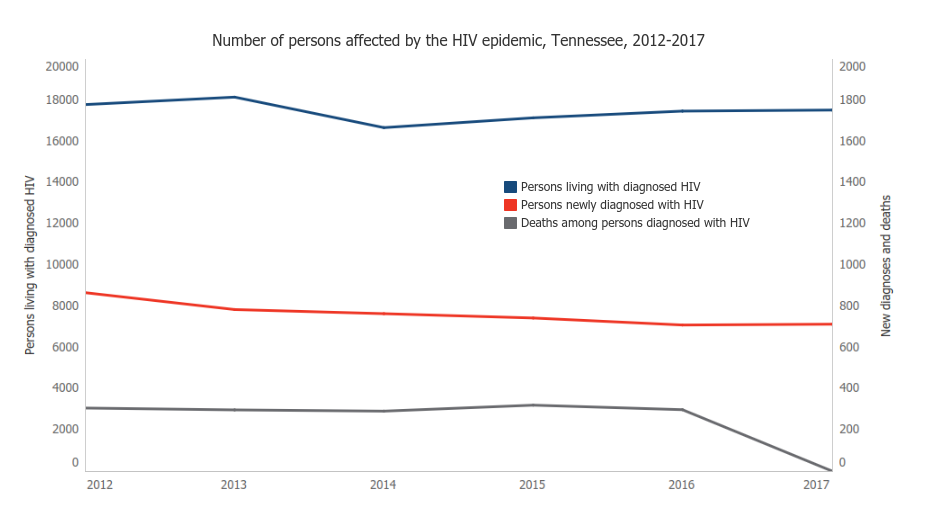

When the epidemic began to spread in the 1980s and 1990s, a positive HIV diagnosis was thought to be a death sentence. However, the disease has become more manageable due to new medical approaches, HIV prevention programs, and available antiretroviral drugs that control HIV infection, strengthen the immune system, and prevent potentially fatal opportunistic infections. There are currently more than 30 antiretroviral drugs on the market.

“Earlier on, when antiretroviral drugs were being developed, people’s entire days were filled up with a schedule of taking different pills,” Whitt says. “It was hard to remain drug compliant. Now, what are currently available are single pills. It makes it much easier for people to remain compliant in taking their one pill versus their 30 pills. That’s really helped in making this a manageable long-term infection without disease.”

Discovery of new information regarding HIV/AIDS, advancement in medical approaches combatting the virus, and the creation of more antiretroviral drugs has shifted both the mortality rates and societal views of the disease. Since 2008, the number of people dying from the disease in Shelby County has steadily decreased — from 159 in 2008 to 44 people in 2012, according to the Health Department.

But the declining death toll doesn’t mean the HIV infection rate should be any less concerning. “I would say our community and the country have really lost focus on HIV,” says Kim Daugherty, executive director of Friends For Life. “The truth of the matter is, HIV still exists, and it’s still a huge health care concern for us all and really needs the attention of the community. One of the best things we could do to help lessen the spread of the HIV virus is really to remove the stigma and prejudice associated with people living with HIV.”

In light of the rapid rate of new infections, President Obama introduced the National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS) in 2010. The policy holds three primary goals: reducing HIV incidence, increasing access to care and optimizing health outcomes, and reducing HIV-related health disparities by 2015.

The Health Department’s goal for combatting HIV/AIDS locally falls in line with the NHAS objective. Strategies include going to the community’s most at-risk areas and providing free testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases, linking more HIV-positive people to care, and requesting help identifying others who may have been impacted or infected.

“When you look at the landscape of Shelby County and Memphis, specifically, [HIV is] something else added to the plate of an already impacted community,” says Anthony Amos, assistant manager of infectious diseases for the Health Department. “Hopefully, some of what we do here can … raise the knowledge of health and economics and all those other things that add to the burden of trying to address the HIV problem in our community.”

The End Game

HIV no longer holds the stigma of being an automatic death sentence. More and more people infected with the virus are able to live long, healthy lives. But the job of trying to reduce the infection level and the subsequent costs to the community goes on. It’s still important to stay up-to-date with your status and practice safe sex, experts warn. And for those who have been infected with the virus, it’s imperative that they indulge in a healthy lifestyle, receive antiretroviral therapy, and be sexually responsible.

Thirteen years after being diagnosed with the disease, Mitchell is enjoying his life. His HIV viral load has been undetected for three-and-a-half years. And he continues to help educate others about the disease, encouraging them to avoid the destructive path that almost took his life.

“Educate yourself. Every day there’s something new on the horizon,” says Mitchell. “Continue to know your status. Reach out and research more and more how you can be helpful in keeping the community safe and more responsible. It starts individually. If we can do that, then we’ll definitely be able to make some changes.”

CDC

CDC

TDH

TDH  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks