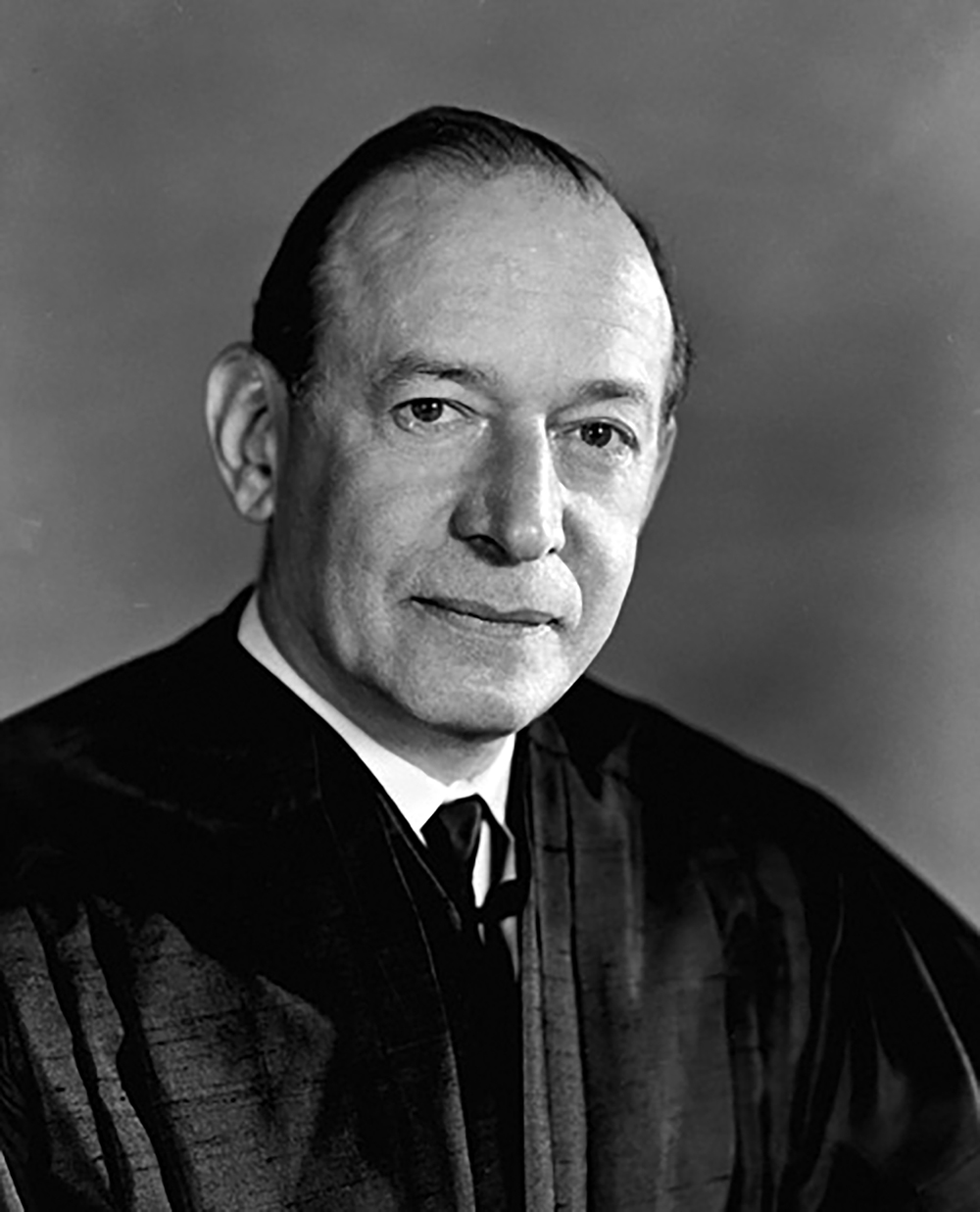

Maybe it’s an age thing, but I find that when I’m alone, my internal monologue often turns into an external mutter-logue. The other day, for instance, I found myself muttering the name of Abe Fortas. Fortas, as you may or may not recall, was a Supreme Court justice from Memphis, appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965. He was a Rhodes College (then called Southwestern College) graduate (like Justice Amy Coney Barrett) before going on to graduate second in his class from Yale Law School.

Known as “Fiddlin’ Fortas” for his prowess on the violin, old Abe had a brilliant career, first as a law professor at Yale, then as an advisor to the Securities and Exchange Commission for President Roosevelt, and later as a delegate appointed by President Truman to help create the nascent United Nations. Fortas was an accomplished man.

Then, in 1969, just four years into his term at SCOTUS, Fortas was discovered to have accepted a $20,000 loan from financier Louis Wolfson, who was being investigated by the Justice Department for possible insider trading. President Nixon, seeing a chance to gain a SCOTUS appointment and push the court in a more conservative direction, asked Fortas to resign. He did.

So why was I muttering this man’s name? Because I’d been reading about the brouhaha(s) surrounding Justice Samuel Alito’s flags flying at his house(s). You know, the upside-down American flag at his home in Washington, D.C., and the QAnon/January 6th conspiracist “Appeal to Heaven” flag at his vacation home in New Jersey. Alito blamed the first flag on his wife, Martha Ann, who allegedly put it up while engaged in a dispute with a neighbor over yard signs. He refused to address the controversy about the second flag.

For the record, the U.S. flag code states that an upside-down American flag can be displayed only “as a signal of dire distress.” I’m not a legal scholar, but I’m thinking a pissing match over a neighbor’s yard sign doesn’t qualify. And I’m thinking Alito knew that.

At this writing, it appears that the Senate is about to stir itself and call Chief Justice Roberts into its chambers to demand some sort of action. No one has yet shown the courage to demand that Alito resign, but at the least, Roberts could urge Alito to recuse himself from any cases related to January 6th. Even that seems unlikely, given that Justice Clarence Thomas has accepted literally millions of dollars worth of gifts and trips from billionaire Harlan Crow — who has had cases before the court — and has suffered absolutely no consequences. Additionally, Thomas’ wife, Ginni, was among those urging Trump administration officials to overturn the 2020 election. Democrats have called for Thomas to recuse himself from election-related cases, a demand he has ignored.

The recusal statute standard that applies to federal judges and justices is not limited to actual bias — it also includes the appearance of bias. For that reason, many legal experts have said that Alito and Thomas should recuse themselves from any January 6th-related cases. Recuse? Resign? Meh. That’s so … 1969.

It’s all about expectations. Lower them far enough, and you can get away with anything. It was expected that Hillary Clinton would be fastidious about her emails. When it was discovered she was sloppy with some of them, the media outrage machine went into front-page overdrive for weeks, probably costing her the 2016 election (and three SCOTUS appointments). Trump’s hiding thousands of top-secret government documents after leaving office? Not so much. That’s just Trump being Trump. In short, if we think someone “should” be acting with integrity and they don’t, it’s news. Otherwise, nah.

So here we are, 55 years after Fortas’ resignation, with a Supreme Court majority mostly hand-picked by the conservative Federalist Society and put forth for Republican presidents to nominate. The justices are mostly Catholic (six of nine members), mostly anti-abortion, and mostly Neanderthal in their attitudes toward the rights of women and minority groups.

Back in 1969, it was expected that Supreme Court justices would avoid any appearance of impropriety. Abe Fortas recognized that what he’d done had irrevocably damaged his standing as a jurist and would become a distraction for the rest of his career at SCOTUS, so he did the honorable thing. Honor. What a concept. It’s a word that’s got me muttering.