The hummingbird swooped down and hovered above a butterfly bush, undaunted by the strong winds and rain. Almost on cue, a second tiny bird zoomed in to deny the interloper a chance at a sweet meal. The two hummingbirds performed a sort of airborne ballet, twirling and spinning in the wind, while fanning their tail feathers to make themselves look larger and more menacing.

Eventually, the trespasser retreated and the second hummer, a female, jockeyed for position on a narrow branch of that same flowering bush. She periodically rose, helicopter-like, just inches above the branch to deliver a warning — chirping and chittering — that intruders were not welcome.

Safe and dry behind the trellised wall of our carport, I watched the aerial combat take place just few feet away as the remnants of Hurricane Francine crashed and thrashed its way throughout the Mid-South. A few days later, Francine, now a low-pressure system, continued to subside. My better half Vicki and I spent a good portion of a wet Sunday morning watching the little birds swoop and twirl — more aerial combat and mid-air ballet.

“Cheap entertainment,” she said with a smile.

“Cheep or cheap?” I asked.

She laughed at my dumb pun. Two hummingbirds zipped past our kitchen’s picture window.

“Crazy birds,” Vicki proclaimed.

Crazy birds, indeed, and I miss them after they’ve moved on.

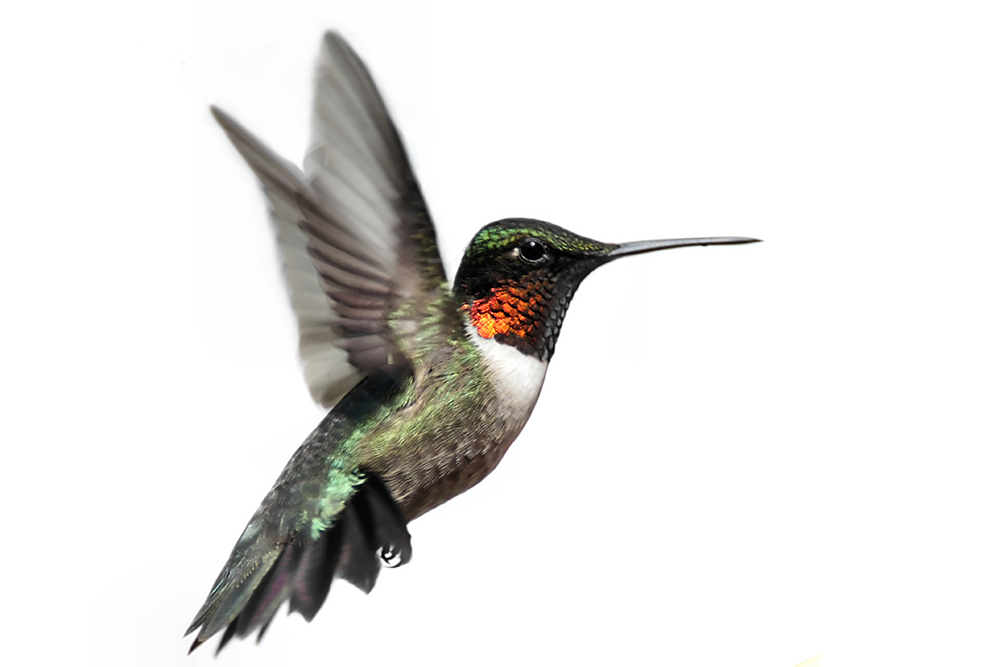

I’ve always been fascinated by hummingbirds, who seemingly defy gravity and conventional aerodynamics in search of a meal and more fuel for their long journey south to remote tropical rainforests. But I also admire these tiny creatures for their perseverance, their tenacity, and their strength. Years ago, I participated in an expressive writing course for cancer survivors and wrote a fictional short story about an old man coming to terms with his own death. He found strength and peace in the hummingbirds and their return, year after year, to his backyard garden. The old man recounted a mythical belief regarding his tiny visitors — that the ancient Aztec people revered hummingbirds for both their colorful beauty and their powerful flight. They believed brave warriors — killed in battle — were reincarnated as hummingbirds.

Maybe our hummers come back every summer to remind me of those wonderful brave warriors no longer here, who can no longer experience a warm, pleasant June morning, or breathe in the fresh air rolling across the green grasses of Shelby Farms Park, or watch a brilliant orange sunset from the banks of the Mississippi River.

Tiny, fluttering reminders that, as the seasons change, we continue moving forward even when our journey becomes difficult.

Or, perhaps, our hummingbirds — we refer to them as “our hummingbirds” while they’re here — return each year simply driven by instinct. We make our backyard inviting to them, with several red-colored feeders and lots of flowering plants. Our next-door neighbor’s wooded backyard provides the birds with shelter and safety. For those “little daredevils,” our gardens are a convenient rest stop along their migratory path. But maybe there’s more to it than just instinct. Regardless, I’ll miss those crazy birds once they’re gone even as I deeply miss my fellow warriors who’ve fallen in battle with a terrible disease.

For two weeks, constant chirping and chittering greeted me anytime I stepped outside and onto our backyard patio. Hummingbirds zooming overhead, fluttering around the feeders, and dive-bombing one another were also constants. I was involved in a few near misses as hummers chased each other through our carport and back up to the trees. As the number of hummingbirds increased, so too did the number of airborne skirmishes. I loved every moment of it.

Our tiny guests were hungry and relentless in their search for a meal. With the days growing shorter, both the humans and the little birds knew summer was coming to an end. Soon those crazy birds would be gone, leaving behind joyful memories, until next year, when a “scout” arrives, usually in April, to check out the food supply situation in our backyard.

A week or so later, summer had officially ended and most of the hummingbirds were gone. We figured they left in a hurry as more rain and wind, this time from Hurricane Helene, made its way towards the Mid-South. The feeders sat empty, while the flowering bushes were commandeered by the remaining butterflies, along with a few honeybees.

I already missed those crazy birds.

For me, hummingbirds symbolize hope and strength. Their survival is intertwined with my own, as being a “survivor” can be difficult at times. Like the old man in my short story, I’m at peace when the little birds return to our backyard each summer. They’re tiny reminders that, even with tenacity and perseverance, the journey is never easy and we must continue to keep the spirit of those fallen warriors in our hearts.

Ken Billett is a freelance writer and short-story author. An 11-year cancer survivor, Ken is a nationally recognized advocate for skin cancer prevention and melanoma treatment research. He and his wife Vicki have called Memphis home for nearly 35 years.