Ever since the novel coronavirus hit U.S. shores, masks have been a talking point. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommends that everyone wear face masks in public, but — because of concerns about scarcity — the CDC originally said there were few benefits to cloth face masks. Though those guidelines have been amended and support for widespread use of masks in scientific circles is more or less a given, the original stance has led to no end of consternation.

“COVID-19 spreads mainly from person to person through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes, talks, or raises their voice,” the CDC states. “These droplets can land in the mouths or noses of people who are nearby or possibly be inhaled into the lungs.” Put simply, masks help you keep your droplets to yourself.

Still, even as some prominent GOP politicians debate the efficacy of masks, State Representative Karen Camper and State Senator Raumesh Akbari announced a new campaign called Mask Up and Live Memphis. Meanwhile, President Trump actually made headlines when he wore a mask for the second time during a recent trip to a facility in North Carolina. Really.

In March, physician and Memphis city councilman Jeff Warren told me during an interview that mask-wearing would be vital to getting a handle on the pandemic. “I think we’re going to be wearing masks for a long time,” he said. “That’s the only reason everybody in the hospital is not infected. All of the countries that you see where they’ve gotten this under control, everybody’s been wearing a mask.” As case numbers have continued to climb, the mask debate has raged on, and Gov. Bill Lee has refused to issue a mandatory mask mandate for Tennesseans, instead favoring an individual “buy in” system, it seems Warren was right in his predictions.

So why has a precaution so simple, so inexpensive, and potentially life- and economy-saving become so polarizing? To shed some light on the mask debate, I spoke with a group of Memphians whose careers have all intersected with masks in one way or another.

Tae Nichol

Tae Nichol

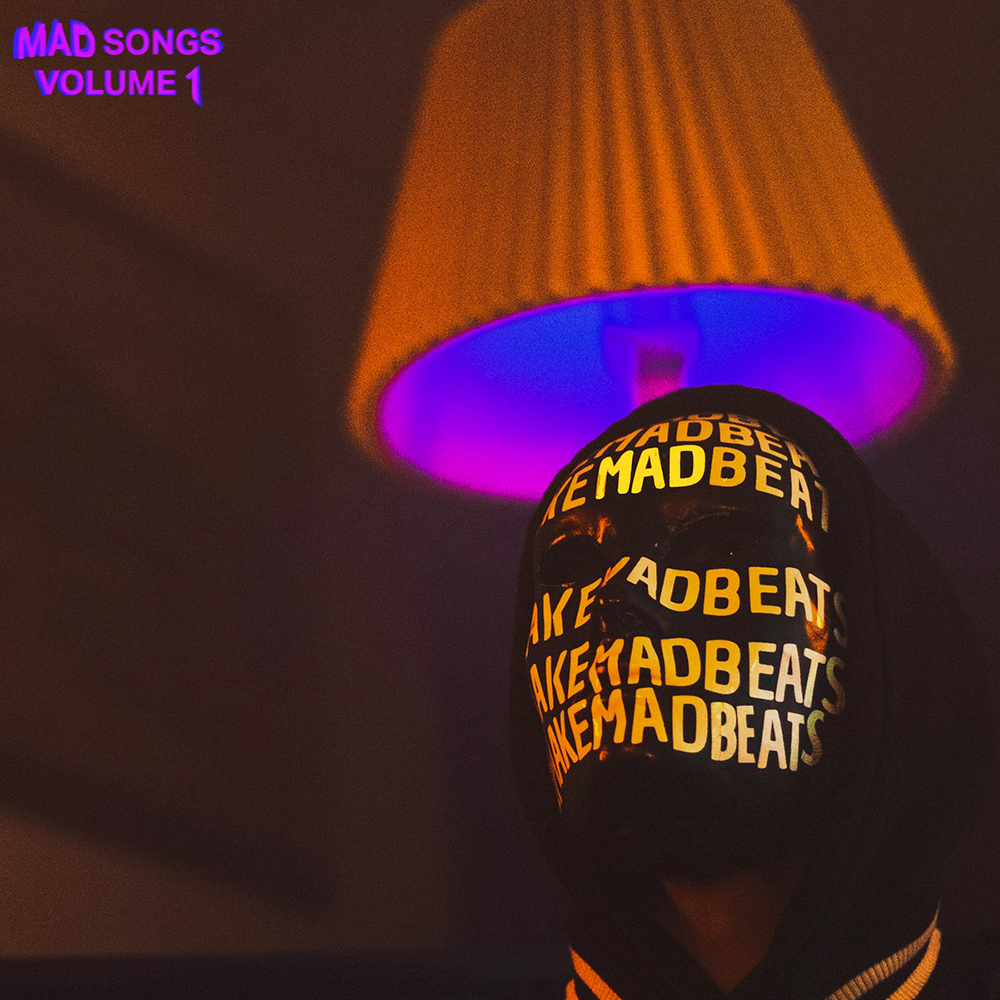

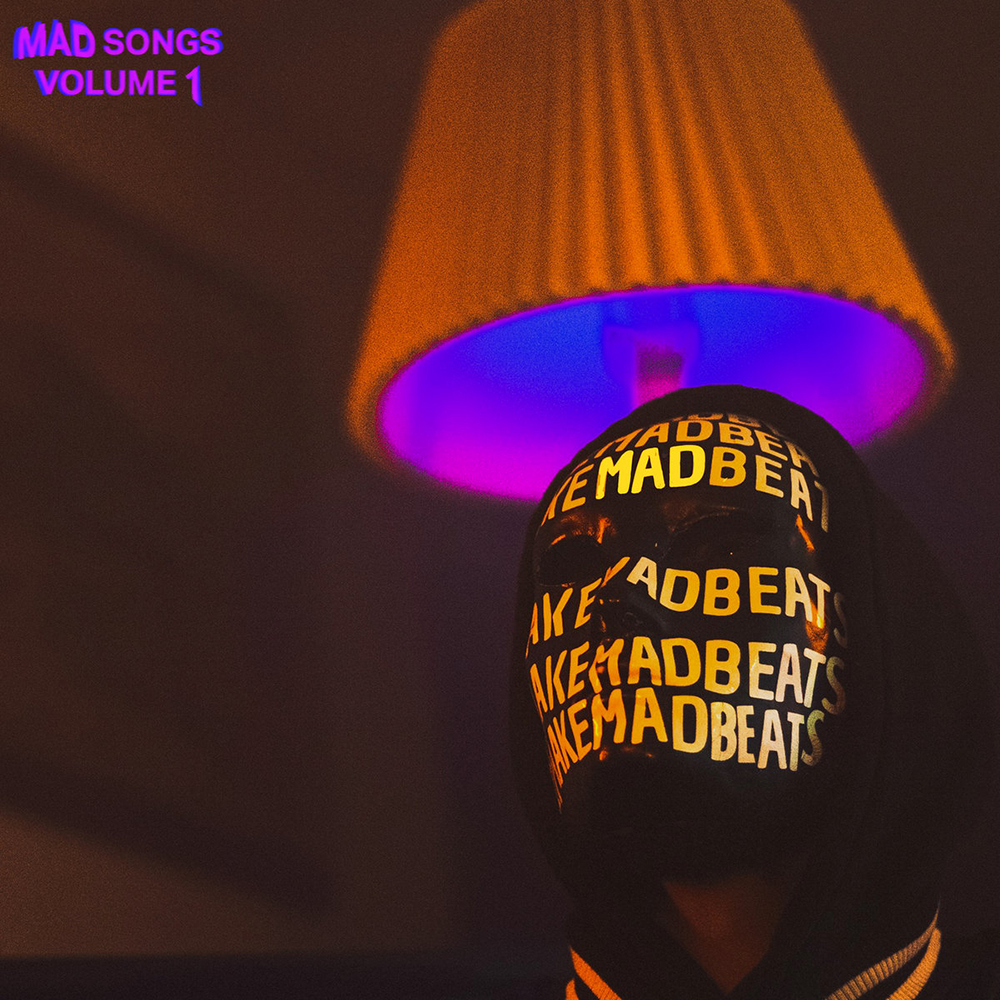

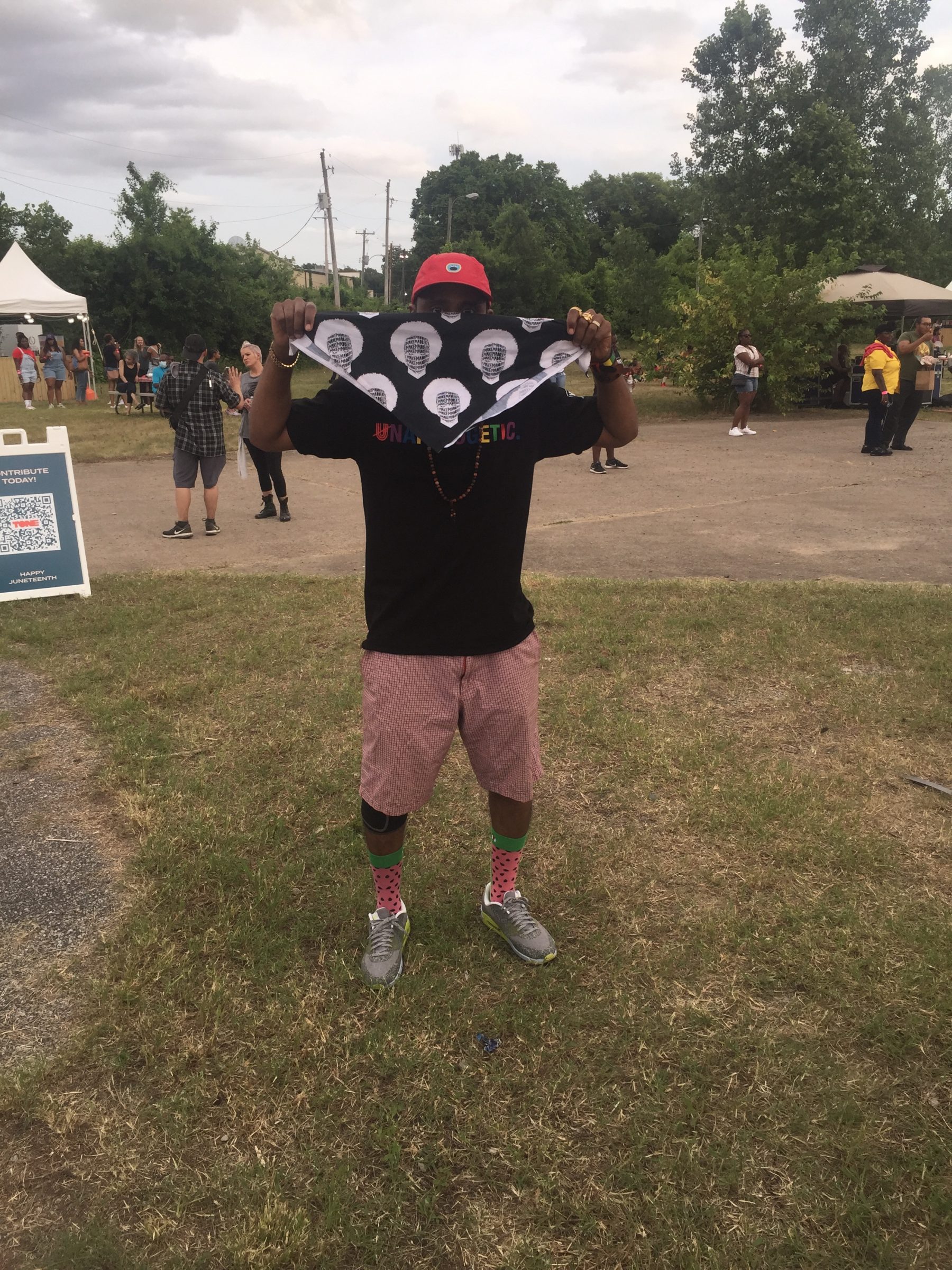

IMAKEMADBEATS wears his dreams on his face.

MAD Masks

Local artist, producer, petition-starter, and Unapologetic founder James Dukes, aka IMAKEMADBEATS, has a “deep history” with masks. In fact, his public persona is indelibly linked to his custom-made mask — also his logo and a promise to himself and his fans — IMAKEMADBEATS. Though his mask isn’t effective against spreading coronavirus, he knows firsthand about the power a mask can hold.

Dukes’ self-branding journey began when he met rapper Busta Rhymes and was given a pearl of wisdom. “He told me that to make it in the industry, you have to first figure out who you are, what you are,” Dukes says, “and you gotta break the knob turning that up.” The message resonated with Dukes, so he began sketching images of a version of himself. “I was trying to draw an understanding of who and what I was, and what I drew was that mask,” he says, remembering finishing the drawing while in sociology class. “I drew what I see when I look in the mirror. If I could draw my dreams, that’s what it would look like.”

That drawing became Dukes’ logo and, eventually, the basis for a custom-made mask. The prolific artist says the mask symbolizes dedication to his goals and his craft; it’s his music-making ethos distilled to the simplest form. “I am using my ability to be a person to convey an idea,” he says. “The mask is the result of that. James has a life. I don’t know how long I’ll be on Earth, but my ideas can live forever.

“It’s easier for an idea to live forever when it goes beyond one person.”

Dukes says he used to send Unapologetic interns to Midtown or Downtown wearing copies of his IMAKEMADBEATS mask. He would hear from people the next day saying it was good to see him. “Nobody really knew it wasn’t me.”

When people see the mask, Dukes explains, their minds immediately fill in what they know it stands for. “The mask is an idea. It represents values. It represents — what I hope it represents and what other people have told me it represents — dedication to brilliance and a seriousness about your craft. It also represents being unapologetic and being who you are unapologetically.”

Dukes traces his interest in alternate identities in part to his time reading comics as a child. “I am 100 percent a comic book kid growing up, my favorite being Venom,” Dukes says, referencing Marvel’s alien antihero, whose black-and-white color scheme is reflected in Dukes’ mask. “You might be able to see the resemblance.” He appreciated “how the symbiote had a life of its own. It wasn’t just a mask or a suit.”

When it comes to the current brouhaha over masks, Dukes has something to say. And he sounds straight-up superheroic: “When people decide to wear a mask or social distance, do what’s right for you and your family. And I would also urge people to recognize no living man has gone through what we’re living through right now. Unless you’re 102 years old.

“We all know whenever you’re going through something you have never been through, you err on the side of caution. Even if you’re walking into a dark room and you don’t know where everything is in that room, you don’t walk in that room like the lights are on. You also don’t walk in that room assuming you know what’s in that room and what can and can’t hurt you. Even if you don’t know if a mask is the way to go, that’s a dark room you ain’t never been in before. You gonna act like you know what’s in that room? Err on the side of caution.”

Jesse Davis

Jesse Davis

University of Memphis professor Marina Levina and daughter Sasha aren’t afraid of these monster and mythical creature masks.

Masks, Movies, and Masculinity

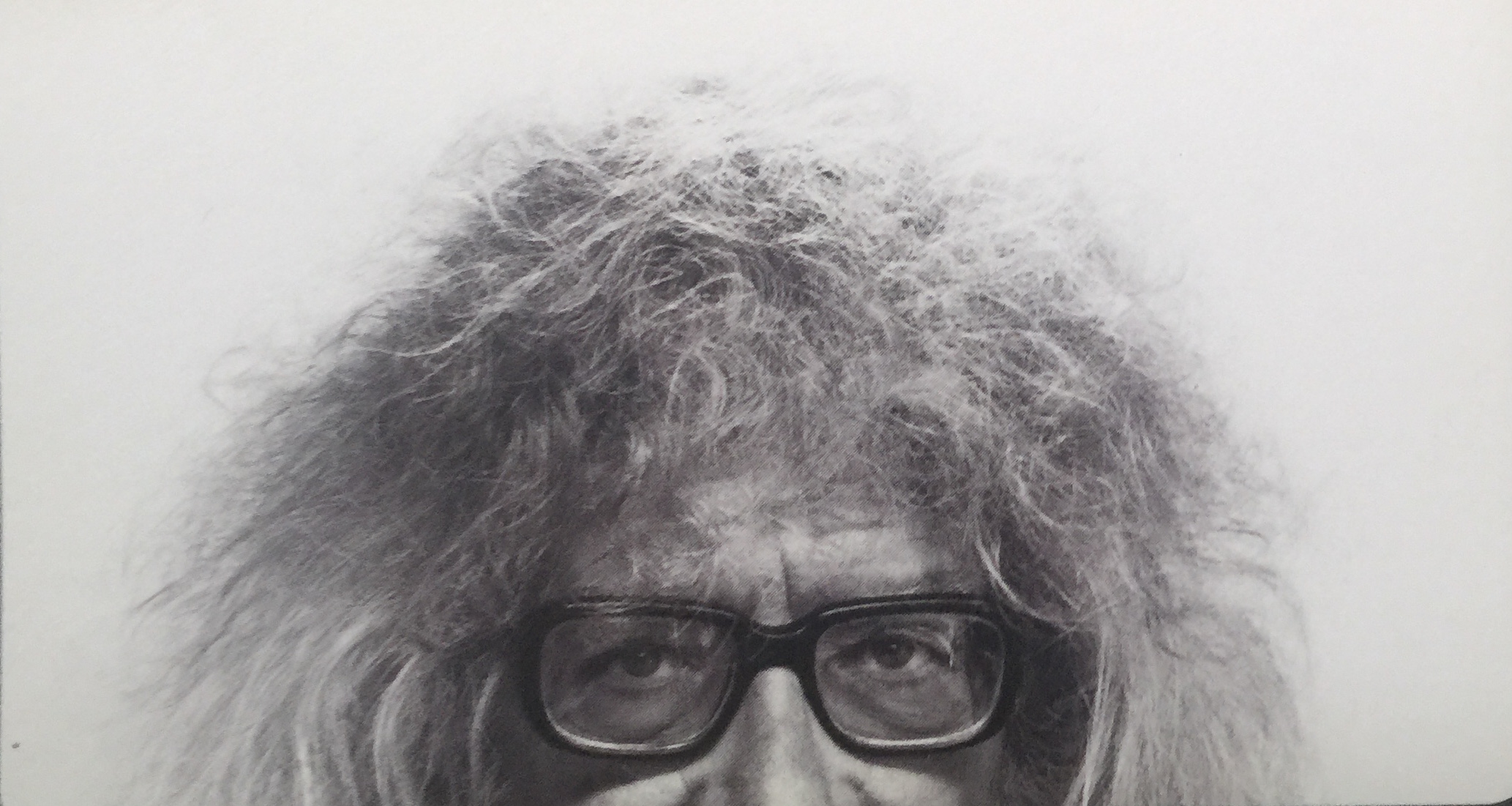

University of Memphis professor Marina Levina wrote the book on pandemics and media — quite literally: Her Pandemics and the Media (Peter Lang Publications) was published in 2014. In it, she writes about the intersection of social norms and mores during a crisis, often as portrayed in monster movies. Imagine a book about pandemics that uses vampire and zombie movies as examples. So it’s something of an understatement when she says, “What’s happening is really in my wheelhouse.”

Levina points out that masks figure prominently in both horror and superhero films — the nation’s collective nightmares and aspirational dreams, respectively. “A lot of it is about persuading men especially to wear a mask because there seems to be some sort of weird cultural connection between masks and masculinity,” she explains.

Referencing a recent statement by the president in which he suggested he looked like the Lone Ranger in his mask, Levina says, “What that was is essentially a statement of ‘I look masculine with a mask on.'” Covering up the eyes is considered masculine, she explains, reeling off a list of fictional macho men who also happen to be masked: “Batman or Lone Ranger or Green Lantern or insert your superhero.” It’s about concealing one’s identity, she adds; moreover, it’s about having the power to conceal one’s identity.

“A mask over the mouth is about concealing weakness,” Levina goes on to explain. “Think about the horror movie serial killers whose mouths are always covered up,” she says, mentioning Michael Myers of Halloween and Hannibal Lecter from The Silence of the Lambs.

Orality in horror movies is often associated with poor impulse control, the professor says. “Like the way Freud used to talk about the oral stage.” It’s also worth noting that Hannibal is a cannibal, and Michael Myers murdered his sister after seeing her have sex. The worst taboos are all woven into their origin stories. Similarly, while the Lone Ranger wears a domino mask that covers his eyes while leaving his oh-so-manly chin on full display, his enemies are often bandits with the lower halves of their faces obscured by bandanas.

The issue comes down to “specifically making men weaker by taking away their choice,” Levina says. “Whereas the mask around the eyes may be seen as someone exercising control over how someone else perceives them.

“Our entire well-being in this country is now situated around convincing men that they’re manly,” she says with a resigned sigh. “It’s the type of emotional labor that women have had to perform constantly and consistently just to keep themselves safe. If that doesn’t make you feel sad and terrible about the state of the world, nothing else will.”

The professor continues: “There is this deep connection between masks and masculinity and the fragility of masculinity in our culture, the fragility of especially white masculinity in this culture,” Levina says. “Which is modeled by, ironically, our president who cannot take a critique, who goes on the attack against private citizens who question him.

“Masks are just another part of that.”

Of course, anti-mask sentiments are not exclusive to men. “There are plenty of women who refuse to wear a mask,” Levina says, pointing out that those who have even a small stake in a given system have some incentive to preserve it. “Women are just as guilty in the affirming of white patriarchy as men are.

“It is very easy to go after individuals,” Levina continues, but she cautions against shaming individual anti-maskers as an effective technique. Humans are not, generally speaking, excellent at risk assessment. That problem is compounded by conflicting messages about the actual severity of the risk. In the end, she says, it all comes down to leadership — or a lack thereof.

“The important thing, the reason right now we are failing at controlling this pandemic is not because of individual behavior of mask-wearing. It is because of complete failure upon federal, state, and local levels of leadership.” The administration has not mass-produced the necessary chemicals to create the required number of tests, Levina says, citing one example. “On a state level, we don’t have a state-wide mask mandate,” she continues. “On the local level, we don’t have a systematic policy about which bars open, which bars close.”

Unfortunately, waiting for clear direction is not an option. It’s up to individuals to take up the cause and wear a mask. And, in this rare instance, maybe it’s safer to be like Michael Myers than Batman and just cover your mouth.

Jesse Davis

Jesse Davis

Memphis College of Art alumna Samilia Colar wears one of her Azalea masks.

From MCA to Maskville

To again reference an interview from the Tiger King stage of quarantine, Warren told me he expected to see individuals doing good business making stylish homemade masks: “This is America. Somebody’s going to figure out how to do something fun and make money off it.” As with his other predictions, he was on the money.

Samilia Colar’s Texstyle Shop has been making and selling masks since April.

“My family is Nigerian,” says the North Carolina-born, now Memphis-based owner of Texstyle Shop. “I, myself, was born in the U.S., but all my siblings, everybody was born in Nigeria. So I grew up with a lot of the fabrics that I use in my work — the Ankara, colorful prints, and all that. I remember being really young and always fascinated by all the materials my mom had and would wear.”

Colar says that “being creative, making things with my hands” was always part of her upbringing. So she decided to pursue art as a career and moved to Memphis to attend Memphis College of Art, where she studied design. Soon she began thinking differently about manipulating materials. “It was a good complement to design.

“I was always drawn to having fabric be functional, and that’s how I got into handbag design.”

Colar graduated from MCA in 2005, and she moved to Philadelphia for a design job. In her free time, she continued to work with fiber arts. “I would do small shows here and there in Philly, and things grew pretty quickly by word of mouth.” So she began putting her products online, and expanded her product line to leather goods. She decided she “really wanted to provide functional products for men as well as women.” Of course, she had no idea at the time that she would one day make and sell face masks, possibly the ideal example of functional products for everyone.

“I’m in Memphis now,” she says, but most of Texstyle Shop’s business is conducted online. “There is a physical address,” for her shop, she says. “That’s my workshop. I’ll do selling workshops throughout the year, but that’s been on pause with COVID-19. Some people come to my shop and pick up from there.”

Colar began making masks in early April, when a friend urged her to use her talents to help combat the spread of coronavirus. She remembers that it was difficult to find masks at the time. “Everyone needed face masks,” she says. “I started working on prototypes one night, and after a few hours I had a pattern I was pleased with,” Colar says of her vibrantly colored masks. “They’ve just been flying off the site ever since.

“The bags definitely took a lot more working through,” Colar continues, but she says she’s learned a lot in the decade or so she’s been designing and crafting fashions and accessories. “This was the quickest turnaround from idea to pattern to finished product, but it wasn’t as tricky or involved as a bag.”

Colar’s masks sport colorful patterns and names that wouldn’t be out of place in an art gallery. Her “Dune” mask, for example, shows undulating waves. “If you have to wear something, better it be something that’s fashionable,” she muses.

“It’s really one small thing to do to help your loved ones stay safe, help those around you to be safe.”

Find Texstyle Shop masks and more at texstyleshop.com. Follow Colar on social media: Instagram: @texstyleshop; Facebook: @texstylebags; Twitter: @texstyleshop

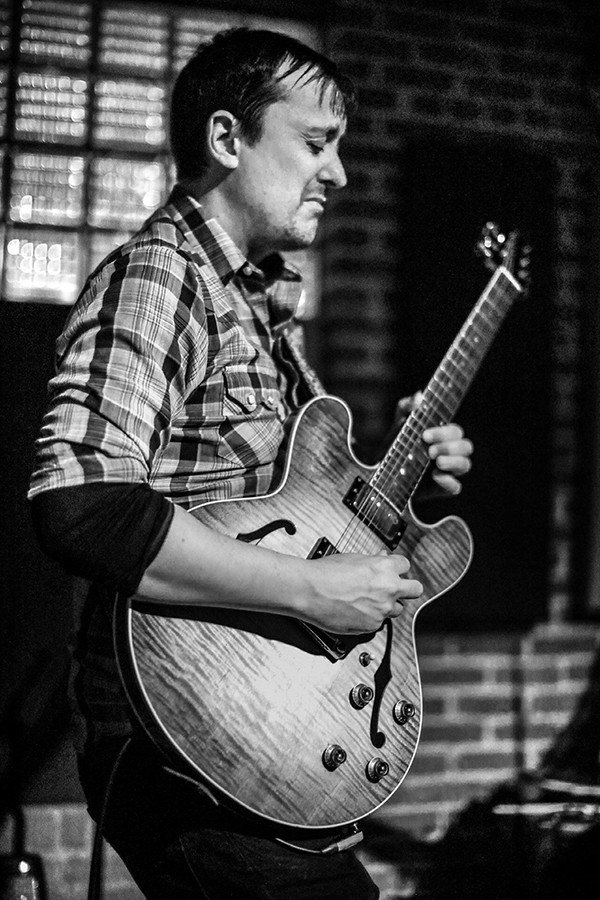

John Haley

John Haley

Grace Byeitima’s Mbabazi House of Style has produced more than 3,000 masks.

Masked by Mbabazi

“We are a social enterprise. We’re headquartered in Uganda,” says Grace Byeitima of Mbabazi House of Style. “We’re a clothing and accessory label that was started with the sole aim of improving the conditions of young women in Uganda. We collaborate with women through training,” Byeitima explains. “Most of what we focus on is turning our challenges into opportunities through creativity.” That challenges-into-opportunities ethos will come in handy when Byeitima makes the decision to produce masks. But first, the origin story.

The company was officially started in 2007, Byeitima says. “We have a workshop that makes and designs most of the products we have. I’d say 80 percent of what I sell here at the shop is made in our workshop in Uganda.”

The Mbabazi shop in Memphis, which Byeitima started in 2016, is the only physical storefront in the world. Though the primary workshop is in Uganda, the physical store there was closed this month. Still, “everything starts there,” Byeitima says of Uganda.

In 2015, she says, “I had gone back home and my mom was like, ‘I can’t believe you don’t have a shop, you don’t have a business in the U.S.’ And I’m like, ‘Is this woman crazy? She thinks it’s that easy?'”

So Byeitima got to work. She did research, talked to people. She knew she needed insurance. She didn’t have credit. But she didn’t let that stop her. Those challenges were, after all, opportunities.

Byeitima got a booth at Merchants at Broad and grew her business from there. When a space became available, she made her move. “I’ve been in this space since 2017,” she says. As her business grew, Byeitima continued to focus on her goals and ideals. “It’s about advocating for African designs through modern fashion,” the entrepreneur explains. “All of what we use is African fabric.

“I did not make masks before the coronavirus,” Byeitima continues, “but I would say really that my life or everything I do has always been to solve an issue. Some of my best designs have been when I really have to solve an issue.

“I was worried. How am I keeping my shop open? I still have rent,” Byeitima remembers. “A lot of people asked me to make some masks.”

So Byeitima mixed up the usual system. Though her designs typically begin out of conversations with her team in Uganda, she began the work on masks in Memphis. “We had gotten a customer who wanted masks, and I had drafted a pattern that we worked with for that specific customer.”

Byeitima challenged herself to make and sell enough masks to pay her rent for the month. She did that and then some. “The moment I started and put it on my social media, people were like, ‘Oh my god! Can you make five? Can you make me 10?'”

Her husband told her to double down on masks, put the design up on her website — and so she did. “Little did we know they were going to announce that the CDC recommended that everybody wear the cloth masks,” Byeitima remembers. “In a space of two days, we got so many orders that we were overwhelmed.” She had to shut down her website — temporarily — until she caught up with the demand.

“To this day, I think we have probably made more than 3,000 masks,” Byeitima says. “I’ve been working with local seamstresses here. I had to find a team to work with. The borders were closed.”

To be on the safe side, Byeitima and her husband pre-wash all their fabrics. “It was hard work,” Byeitima admits. “It was just me and my husband in the shop.” They did everything they could to work in the safest way they possibly could.

When asked if she has anything she would say to Memphians about the current health crisis, Byeitima displays the same people-first ethos that guides her business. “Wear a mask. It doesn’t cost you anything,” she says. “Protect other people. I would be honest and tell people, like, it’s more protecting the other person than yourself, but if we all do it then we protect each other.”

Mbabazi House of Style is located at 2553 Broad (901) 303-9347. Find Mbabazi designs at mbabazistyles.com.

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon  Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon  Courtesy Ed Finney

Courtesy Ed Finney  Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon  Courtesy Stephen Lee

Courtesy Stephen Lee  Darnell Henderson II

Darnell Henderson II  David Patten Mason

David Patten Mason  Billy Fox

Billy Fox  Margaret Deloach

Margaret Deloach  Tae Nichol

Tae Nichol  Jesse Davis

Jesse Davis  Jesse Davis

Jesse Davis  John Haley

John Haley  David Vaughn Mason

David Vaughn Mason  Ziggy Mack

Ziggy Mack  Don Perry

Don Perry  Matt White

Matt White