In January, city councilman Edmund Ford declared 2007 the year of truth.

Now, we’re not saying it wasn’t a truthful year, but maybe — especially since Congressman Steve Cohen found himself on The Colbert Report — it was the year of what Colbert calls truthiness.

Rickey Peete, under an indictment of bribery, resigned again from the City Council. Ford, facing a similar indictment, decided to stay on the council until his term ended. When the election rolled around, Ford’s son ran and won his father’s former seat.

Below is a month-by-month guide to 2007. Or, in all truthiness, as close as we could get.

January

At his annual New Year’s Day Prayer breakfast, Mayor Willie Herenton proposes building a brand-new football stadium to replace the aging Liberty Bowl Memorial Stadium. Meanwhile, the City Council commits $15 million to upgrade bathrooms and disabled access at the Liberty Bowl.

Memphis Zoo female panda Ya Ya gives Le Le the cold shoulder when he tries to impress her by doing handstands, apparently a panda mating ritual.

Memphis-based Stax Records turns 50 and celebrates the big day with a party not in Memphis but in New York City.

February

A national survey ranks Memphis number one in the amount of time we spend watching television.

City Council member Edmund Ford racks up a $16,000 utility bill, but his power stays on. Turns out he and other politicians, like E.C. Jones, Myron Lowery, and Jack Sammons, are on a special VIP list.

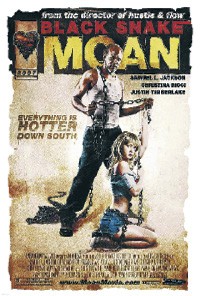

Memphis director Craig Brewer’s Black Snake Moan, starring Samuel L. Jackson and Christina Ricci, premieres. Brewer held off on its release to give people plenty of time to forget that other Samuel L. Jackson film with a serpent title: Snakes on a Plane.

March

Congressman Steve Cohen appears on Comedy Central’s The Colbert Report. Host Steven Colbert asks Cohen if he’s the first Jew from Tennessee.

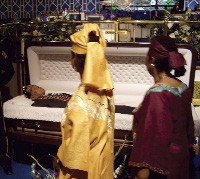

Church of God in Christ (COGIC) presiding bishop G.E. Patterson dies of heart failure on March 20th. Bishop Charles Blake of the West Angeles COGIC in Los Angeles is named presiding bishop at the annual convocation in November.

Twenty-five-year-old Anna Clifford makes national news after she appears in a mugshot with a 12-inch Mohawk. The attention started after her mugshot, the result of a DUI charge after leaving a Midtown bar, was posted on TheSmokingGun.com.

April

Dale Mardis is sentenced to 15 years in prison for the slaying of code-enforcement inspector Mickey Wright. Mardis admitted to killing Wright, then dismembering and burning the body. Wright’s family becomes outraged that Mardis only received a charge of second-degree murder.

Thieves steal more than $11,000 worth of brass valves from the Sears Crosstown building’s plumbing and fire-control system. It is just one of countless “scrap metal” thefts — air conditioning parts and vehicle catalytic converters are also routinely stolen — across the city during the year.

In Selmer, Tennessee, Mary Winkler is convicted of manslaughter in the shooting death of her preacher husband Matthew Winkler. While on the stand, she showed a pair of white, high-heeled shoes she said her husband forced her to wear.

May

Former Senator John Ford is convicted of bribery. Ophelia Ford — who won John’s vacated state Senate seat — falls off of a barstool in Nashville after informing attendees of a Senate hearing that they “need to get knowledged.”

Zookeepers at the Memphis Zoo artificially inseminate Ya Ya, starting a panda pregnancy watch that ultimately ends with a miscarriage.

After playing “Ice Ice Baby” one time too many, Raiford’s Hollywood Disco closes, only to reopen under new ownership in the fall.

June

Robert F.X. Sillerman, owner of Elvis Presley’s image, announces plans to invest $250 million in upgrades to both sides of Elvis Presley Boulevard around Graceland.

John McCain threatens to name FedEx founder Fred Smith to his cabinet if elected president.

July

The Memphis Light Gas and Water board decides to sell Memphis Networx to Colorado-based Communications Infrastructure Investments at a more than $28 million loss.

August

A Raleigh man grabs national headlines when he became the victim of a gunshot wound — inflicted by his dog.

An overzealous Elvis fan steals one of the King’s firearms from a museum across the street from Graceland but “dumps” the pistol in a nearby port-a-potty.

September

Local Air America station trades liberal politics for sports scores.

An FBI report says Memphis is the most dangerous city in the country. U of M football player Taylor Bradford is shot on campus in a botched robbery attempt and later dies at the Med.

October

Noted photographer Ernest Withers dies.

A Memphis high school student shoots his friend during an English class. The friend recovers; the Memphis city school district asks its schools to beef up security.

November

Bruce Thompson is indicted on corruption charges. The former county commissioner allegedly received $260,000 in consulting fees as part of an MCS construction job.

Though Mayor Willie Herenton once vowed he would conduct a national search for a new president of MLGW, after being reelected for his gazillionth term, Herenton appoints the city’s public works director, Jerry Collins, to the job.

New evidence in the West Memphis Three case points to animal attacks to explain evidence once considered signs that the young victims were part of a Satanic ritual.

December

While waiting for outdoor retailer Bass Pro to move forward with plans for The Pyramid, county commissioners hear an alternative reuse plan: a $250 million indoor theme park with a 300- to 400-room hotel and a shopping mall.

Local Scientologists put their Midtown mansion on the market.

Justin Timberlake’s family buys the Big Creek golf course in Millington and promises a new clubhouse, new golf carts, and maintenance to the course itself. He’s bringing BigCreek back!