Yesterday, news and social media erupted with celebrations of the great jazz composer and collaborator, Sun Ra, who was born on May 22, 1914 — and rightly so. From the 1950s until his death in 1993, the musical innovator’s refusal to bow to the conventions and niceties of his day was prescient, even prophetic. Yet the most committed devotees of his story noted the birthday celebrations — ranging from discounted Ra LPs at Goner Records to the New York radio station WKCR broadcasting a full 24 hours of his music — with no little irony.

Ra himself had no use for birthdays, especially his own. In John F. Szwed’s Space is the Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra, the musician is quoted as saying, “I’m not human. I never called anybody ‘mother’… I’ve separated myself from everything that in general you call life.” This, he explained, impacted the very notion of a birthday in particular. “I don’t remember when I was born. I’ve never memorized it. And this is exactly what I want to teach everybody: that is is important to liberate oneself from the obligation to be born, because this experience doesn’t help us at all. It is important for the planet that its inhabitants do not believe in being born, because whoever is born has to die.”

With that in mind, it’s worth noting that Sun Ra seems to be living his best life, even as we approach the 30th anniversary of his death on May 30th. Respected by only a narrow niche of jazz aficionados half a century ago, his music has continued to grow in renown to this day, both globally and right here in Memphis. The upshot being that Sun Ra’s music is more available than ever.

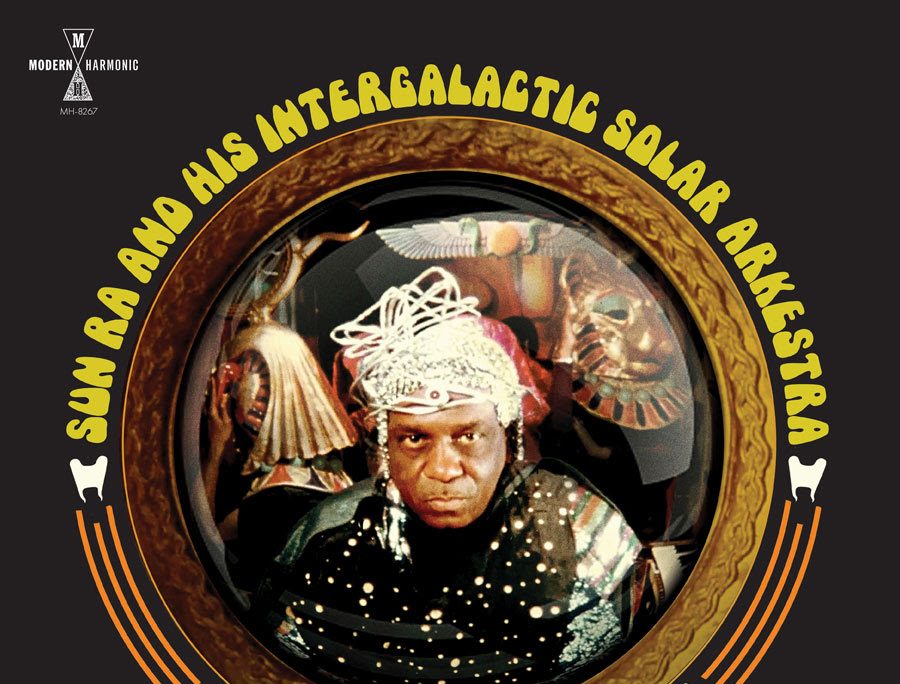

Case in point: the new mega-collection of three LP’s (or two CD’s), a BluRay and a DVD of material from his 1974 film, Space is the Place, courtesy of the Sundazed label’s imprint, Modern Harmonic. Not only is the feature film made available with greater clarity than ever, the soundtrack can be enjoyed as a stand-alone experience, and an entire album of unreleased material is also included.

Of course, Sun Ra contained multitudes, helping to shape free jazz even as he cherished the old Fletcher Henderson big band arrangements that he exhorted his band to learn note-for-note. Typically, one samples the various eras of Ra’s proclivities with some record-collecting time travel, with his earliest and latest years being more “conventional,” and his middle period, from the late ’60s through the ’70s, being the most “out.” Yet with this package, due to the film’s semi-autobiographical purview, one can hear all of that and more.

For the uninitiated, Ra built up a whole mythology around himself that was in full flower when the movie was made. His penchant for Afrocentric imagery and outer space themes may seem gimmicky to some, but a closer inspection reveals it to be his way of shaking off preconceptions so as to foster a more imaginative state in viewers and listeners. And the ideas — musical, theatrical, and political — that he hoped to put across were very serious indeed.

“It’s after the end of the world — don’t you know that yet?” says a voice as the film begins, and the low-budget spaceship and alien world setting of the first scenes frame all that comes after, with science fiction’s air of epochal speculation. And right from the start, the serious political intent behind such whimsy is apparent.

As Ra wanders a strange planet, bedecked in the raiment of a pharaoh, he notes that the Black people of earth could thrive there. “Without any white people there, they could drink in the beauty of this planet.” To confront the suffering of earth, he makes it clear that he’ll defy the laws of nature itself. “Consider time has officially ended. We work on the other side of time,” he quips, before proposing to “teleport the whole planet [earth] here through music.” Then the film cuts to the title: SPACE IS THE PLACE.

The realm of the fantastic permeates the film, even as it delves into the rough living in Chicago’s poorer neighborhoods, and a meandering tale of Ra gambling with a pimp-like character known as The Overseer. Without spoiling too much of it, rest assured that the film is chock-full of surprises and unexpected turns — and music.

That’s the point of the three LP’s, of course, and they make for galvanizing listening on their own. This was at the height of Ra’s embrace of experimentalism, but upon deeper listening, sonic structures emerge, as his band, the Arkestra, slaloms from wildly percussive jams to synthesizer squelches to mambo to something approaching doo-wop. Voices chant “Calling Planet Earth!” A segment featuring Ra as “Sonny Ray,” a pianist in a strip club, starts with his renditions of classic boogie woogie, only to become more eccentric and frantic (causing patrons’ glasses to explode in the film).

All of these sounds are conveyed in glorious mono, as originally intended, yet the arrangements and recording techniques help create a spaciousness that rivals the most stereophonic mixes. And for those who truly get off on vinyl, the tri-color LPs green, gold, and silver shine like gems. True, the box set runs a hefty $125, but the experience is so immersive, the world-building so complete, that any listeners looking for something fresh (from half a century ago!) will find it well worth the price.